ISONIAZID- isoniazid tablet

MIKART, INC.

----------

ISONIAZID TABLETS, USP

WARNING

Severe and sometimes fatal hepatitis associated with isoniazid therapy has been reported and may occur or may develop even after many months of treatment. The risk of developing hepatitis is age related. Approximate case rates by age are: less than 1 per 1,000 for persons under 20 years of age, 3 per 1,000 for persons in the 20-34 year age group, 12 per 1,000 for persons in the 35-49 year age group, 23 per 1,000 for persons in the 50-64 year age group, and 8 per 1,000 for persons over 65 years of age. The risk of hepatitis is increased with daily consumption of alcohol. Precise data to provide a fatality rate for isoniazid-related hepatitis is not available; however, in a U.S. Public Health Service Surveillance Study of 13,838 persons taking isoniazid, there were 8 deaths among 174 cases of hepatitis.

Therefore, patients given isoniazid should be carefully monitored and interviewed at monthly intervals. For persons 35 and older, in addition to monthly symptom reviews, hepatic enzymes (specifically, AST and ALT (formerly SGOT and SGPT, respectively)) should be measured prior to starting isoniazid therapy and periodically throughout treatment. Isoniazid-associated hepatitis usually occurs during the first three months of treatment. Usually, enzyme levels return to normal despite continuance of drug, but in some cases progressive liver dysfunction occurs. Other factors associated with an increased risk of hepatitis include daily use of alcohol, chronic liver disease and injection drug use. A recent report suggests an increased risk of fatal hepatitis associated with isoniazid among women, particularly black and Hispanic women. The risk may also be increased during the post-partum period. More careful monitoring should be considered in these groups, possibly including more frequent laboratory monitoring. If abnormalities of liver function exceed three to five times the upper limit of normal, discontinuation of isoniazid should be strongly considered. Liver function tests are not a substitute for a clinical evaluation at monthly intervals or for the prompt assessment of signs or symptoms of adverse reactions occurring between regularly scheduled evaluations. Patients should be instructed to immediately report signs or symptoms consistent with liver damage or other adverse effects. These include any of the following: unexplained anorexia, nausea, vomiting, dark urine, icterus, rash, persistent paresthesias of the hands and feet, persistant fatigue, weakness or fever of greater than 3 days duration and/or abdominal tenderness, especially right upper quadrant discomfort. If these symptoms appear or if signs suggestive of hepatic damage are detected, isoniazid should be discontinued promptly, since continued use of the drug in these cases has been reported to cause a more severe form of liver damage. Patients with tuberculosis who have hepatitis attributed to isoniazid should be given appropriate treatment with alternative drugs. If isoniazid must be reinstituted, it should be reinstituted only after symptoms and laboratory abnormalities have cleared. The drug should be restarted in very small and gradually increasing doses and should be withdrawn immediately if there is any indication of recurrent liver involvement.

Preventive treatment should be deferred in persons with acute hepatic diseases.

DESCRIPTION:

Isoniazid is an antibacterial available as 100 mg and 300 mg tablets for oral administration. Each tablet also contains as inactive ingredients: colloidal silicon dioxide, croscarmellose sodium, microcrystalline cellulose and stearic acid.

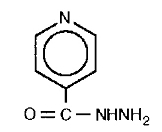

Isoniazid is chemically known as isonicotinyl hydrazine or isonicotinic acid hydrazide. It has an empirical formula of C6H7N30 and a molecular weight of 137.14. It has the following structure:

Isoniazid is odorless, and occurs as a colorless or white crystalline powder or as white crystals. It is freely soluble in water, sparingly soluble in alcohol, and slightly soluble in chloroform and in ether. Isoniazid is slowly affected by exposure to air and light.

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY:

Within 1 to 2 hours after oral administration, isoniazid produces peak blood levels which decline to 50 percent or less within 6 hours. It diffuses readily into all body fluids (cerebrospinal, pleural, and ascitic fluids), tissues, organs, and excreta (saliva, sputum, and feces). The drug also passes through the placental barrier and into milk in concentrations comparable to those in the plasma. From 50 to 70 percent of a dose of isoniazid is excreted in the urine in 24 hours.

Isoniazid is metabolized primarily by acetylation and dehydrazination. The rate of acetylation is genetically determined. Approximately 50 percent of Blacks and Caucasians are “slow inactivators” and the rest are “rapid inactivators”; the majority of Eskimos and Orientals are “rapid inactivators.”

The rate of acetylation does not significantly alter the effectiveness of isoniazid. However, slow acetylation may lead to higher blood levels of the drug and, thus, to an increase in toxic reactions.

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) deficiency is sometimes observed in adults with high doses of isoniazid and is considered probably due to its competition with pyridoxal phosphate for the enzyme apotryptophanase.

Mechanism of Action:

Isoniazid inhibits the synthesis of mycolic acids, an essential component of the bacterial cell wall. At therapeutic levels isoniazid is bacteriocidal against actively growing intracellular and extracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis organisms.

Isoniazid resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli develop rapidly when isoniazidmonotherapy is administered.

Microbiology:

Two standardized in vitro susceptibility methods are available for testing isoniazid against Mycobacterium tuberculosis organisms. The agar proportion method (CDC or NCCLS M24-P) utilizes middlebrook 7HlO medium impregnated with isoniazid at two final concentrations, 0.2 and 1.0 mcg/mL. MIC99 values are calculated by comparing the quantity of organisms growing in the medium containing drug to the control cultures. Mycobacterial growth in the presence of drug ≥ 1% of the control indicates resistance.

The radiometric broth method employs the BACTEC 460 machine to compare the growth index from untreated control cultures to cultures grown in the presence of 0.2 and 1.0 mcg/mL of isoniazid. Strict adherence to the manufacturer's instructions for the sample processing and data interpretation is required for this assay.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with an MIC99≤ 0.2 mcg/mL are considered to be susceptible to isoniazid. Susceptibility test results obtained by the two different methods discussed above cannot be compared unless equivalent drug concentrations are evaluated.

The clinical relevance of in vitro susceptibility for mycobacterium species other than M. tuberculosis using either the BACTEC or the proportion method has not been determined.

INDICATIONS AND USAGE:

Isoniazid is recommended for all forms of tuberculosis in which organisms are susceptible. However, active tuberculosis must be treated with multiple concomitant antituberculosis medications to prevent the emergence of drug resistance. Single-drug treatment of active tuberculosis with isoniazid, or any other medication, is inadequate therapy.

Isoniazid is recommended as preventive therapy for the following groups, regardless of age. (Note: the criterion for a positive reaction to a skin test (in millimeters of induration) for each group is given in parentheses):

- 1.

- Persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (≥ 5 mm) and persons with risk factors for HIV infection whose HIV infection status is unknown but who are suspected of having HIV infection.

Preventive therapy may be considered for HIV infected persons who are tuberculin-negative but belong to groups in which the prevalence of tuberculosis infection is high. Candidates for preventive therapy who have HIV infection should have a minimum of 12 months of therapy. - 2.

- Close contacts of persons with newly diagnosed infectious tuberculosis (≥ 5 mm). In addition, tuberculin-negative (< 5 mm) children and adolescents who have been close contacts of infectious persons within the past 3 months are candidates for preventive therapy until a repeat tuberculin skin test is done 12 weeks after contact with the infectious source. If the repeat skin test is positive (> 5 mm), therapy should be continued.

- 3.

- Recent converters, as indicated by a tuberculin skin test (≥ 10 mm increase within a 2-year period for those < 35 years old; ≥ 15 mm increase for those ≥ 35 years of age). All infants and children younger than 4 years of age with a > 10 mm skin test are included in this category.

- 4.

- Persons with abnormal chest radiographs that show fibrotic lesions likely to represent old healed tuberculosis (≥ 5 mm). Candidates for preventive therapy who have fibrotic pulmonary lesions consistent with healed tuberculosis or who have pulmonary silicosis should have 12 months of isoniazid or 4 months of isoniazid and rifampin, concomitantly.

- 5.

- Intravenous drug users known to be HIV-seronegative (> 10 mm).

- 6.

- Persons with the following medical conditions that have been reported to increase the risk of tuberculosis (≥ 10 mm): silicosis; diabetes mellitus; prolonged therapy with adrenocorticosteroids; immunosuppressive therapy; some hematologic and reticuloendothelial diseases, such as leukemia or Hodgkin's disease; end-stage renal disease; clinical situations associated with substantial rapid weight loss or chronic undernutrition (including: intestinal bypass surgery for obesity, the postgastrectomy state (with or without weight loss), chronic peptic ulcer disease, chronic malabsorption syndromes, and carcinomas of the oropharynx and upper gastrointestinal tract that prevent adequate nutritional intake). Candidates for preventive therapy who have fibrotic pulmonary lesions consistent with healed tuberculosis or who have pulmonary silicosis should have 12 months of isoniazid or 4 months of isoniazid and rifampin, concomitantly.

Additionally, in the absence of any of the above risk factors, persons under the age of 35 with a tuberculin skin test reaction of 10 mm or more are also appropriate candidates for preventive therapy if they are a member of any of the following high-incidence groups:

- 1.

- Foreign-born persons from high-prevalence countries who never received BCG vaccine.

- 2.

- Medically underserved low-income populations, including high-risk racial or ethnic minority populations, especially blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans.

- 3.

- Residents of facilities for long-term care (e.g., correctional institutions, nursing homes, and mental institutions).

Children who are less than 4 years old are candidates for isoniazid preventive therapy if they have > 10 mm induration from a PPD Mantoux tuberculin skin test.

Finally, persons under the age of 35 who a) have none of the above risk factors (1-6); b) belong to none of the high-incidence groups; and c) have a tuberculin skin test reaction of 15 mm or more, are appropriate candidates for preventive therapy.

The risk of hepatitis must be weighed against the risk of tuberculosis in positive tuberculin reactors over the age of 35. However, the use of isoniazid is recommended for those with the additional risk factors listed above (1-6) and on an individual basis in situations where there is likelihood of serious consequences to contacts who may become infected.

CONTRAINDICATIONS:

Isoniazid is contraindicated in patients who develop severe hypersensitivity reactions, including drug-induced hepatitis; previous isoniazid-associated hepatic injury; severe adverse reactions to isoniazid such as drug fever, chills, arthritis; and acute liver disease of any etiology.

PRECAUTIONS:

General:

All drugs should be stopped and an evaluation made at the first sign of a hypersensitivity reaction. If isoniazid therapy must be reinstituted, the drug should be given only after symptoms have cleared. The drug should be restarted in very small and gradually increasing doses and should be withdrawn immediately if there is any indication of recurrent hypersensitivity reaction.

Use of isoniazid should be carefully monitored in the following:

- 1.

- Daily users of alcohol. Daily ingestion of alcohol may be associated with a higher incidence of isoniazid hepatitis.

- 2.

- Patients with active chronic liver disease or severe renal dysfunction.

- 3.

- Age > 35.

- 4.

- Concurrent use of any chronically administered medication.

- 5.

- History of previous discontinuation of isoniazid.

- 6.

- Existence of peripheral neuropathy or conditions predisposing to neuropathy.

- 7.

- Pregnancy.

- 8.

- Injection drug use.

- 9.

- Women belonging to minority groups, particularly in the post-partum period.

- 10.

- HIV seropositive patients.

Laboratory Tests:

Because there is a higher frequency of isoniazid associated hepatitis among certain patient groups, including age > 35, daily users of alcohol, chronic liver disease, injection drug use and women belonging to minority groups, particularly in the post-partum period, transaminase measurements should be obtained prior to starting and monthly during preventative therapy, or more frequently as needed. If any of the values exceed three to five times the upper limit of normal, isoniazid should be temporarily discontinued and consideration given to restarting therapy.

Drug Interactions:

Food: Isoniazid should not be administered with food. Studies have shown that the bioavailability of isoniazid is reduced significantly when administered with food.

Acetaminophen: A report of severe acetaminophen toxicity was reported in a patient receiving isoniazid. It is believed that the toxicity may have resulted from a previously unrecognized interaction between isoniazid and acetaminophen and a molecular basis for this interaction has been proposed. However, current evidence suggests that isoniazid does induce P-450IIE1, a mixed-function oxidase enzyme that appears to generate the toxic metabolites, in the liver. Furthermore, it has been proposed that isoniazid resulted in induction of P-450IIE1 in the patient's liver which, in turn, resulted in a greater proportion of the ingested acetaminophen being converted to the toxic metabolites. Studies have demonstrated that pretreatment with isoniazid potentiates acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in rats1,2.

Carbamazepine: Isoniazid is known to slow the metabolism of carbamazepine and increase its serum levels. Carbamazepine levels should be determined prior to concurrent administration with isoniazid, signs and symptoms of carbamazepine toxicity should be monitored closely, and appropriate dosage adjustment of the anticonvulsant should be made3.

Ketoconazole: Potential interaction of ketoconazole and isoniazid may exist. When ketoconazole is given in combination with isoniazid and rifampin the AUC of ketoconazole is decreased by as much as 88% after 5 months of concurrent isoniazid and rifampin therapy4.

Phenytoin: Isoniazid may increase serum levels of phenytoin. To avoid phenytoin intoxication, appropriate adjustment of the anticonvulsant should be made5,6.

Theophylline: A recent study has shown that concomitant administration of isoniazid and theophylline may cause elevated plasma levels of theophylline, and in some instances a slight decrease in the elimination of isoniazid. Since the therapeutic range of theophylline is narrow, theophylline serum levels should be monitored closely, and appropriate dosage adjustments of theophylline should be made7.

Valproate: A recent case study has shown a possible increase in the plasma level of valproate when co-administered with isoniazid. Plasma valproate concentration should be monitored when isoniazid and valproate are co-administered, and appropriate dosage adjustments of valproate should be made8.

Carcinogenesis and Mutagenesis:

Isoniazid has been shown to induce pulmonary tumors in a number of strains of mice. Isoniazid has not been shown to be carcinogenic in humans. (Note: a diagnosis of mesothelioma in a child with prenatal exposure to isoniazid and no other apparent risk factors has been reported). Isoniazid has been found to be weakly mutagenic in strains TA 100 and TA 1535 of Salmonella typhimurium (Ames assay) without metabolic activation.

Pregnancy:

Teratogenic effects: Pregnancy Category C:

Isoniazid has been shown to have an embryocidal effect in rats and rabbits when given orally during pregnancy. Isoniazid was not teratogenic in reproduction studies in mice, rats and rabbits. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Isoniazid should be used as a treatment for active tuberculosis during pregnancy because the benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. The benefit of preventive therapy also should be weighed against a possible risk to the fetus. Preventive therapy generally should be started after delivery to prevent putting the fetus at risk of exposure; the low levels of isoniazid in breast milk do not threaten the neonate. Since isoniazid is known to cross the placental barrier, neonates of isoniazid treated mothers should be carefully observed for any evidence of adverse effects.

Nursing Mothers:

The small concentrations of isoniazid in breast milk do not produce toxicity in the nursing newborn; therefore, breast feeding should not be discouraged. However, because levels of isoniazid are so low in breast milk, they can not be relied upon for prophylaxis or therapy of nursing infants.

ADVERSE REACTIONS:

The most frequent reactions are those affecting the nervous system and the liver.

Nervous System Reactions:

Peripheral neuropathy is the most common toxic effect. It is dose-related, occurs most often in the malnourished and in those predisposed to neuritis (e.g., alcoholics and diabetics), and is usually preceded by paresthesias of the feet and hands. The incidence is higher in “slow inactivators”.

Other neurotoxic effects, which are uncommon with conventional doses, are convulsions, toxic encephalopathy, optic neuritis and atrophy, memory impairment and toxic psychosis.

Hepatic Reactions:

See boxed warning. Elevated serum transaminase (SGOT; SGPT), bilirubinemia, bilirubinuria, jaundice and occasionally severe and sometimes fatal hepatitis. The common prodromal symptoms of hepatitis are anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, malaise and weakness. Mild hepatic dysfunction, evidenced by mild and transient elevation of serum transaminase levels occurs in 10 to 20 percent of patients taking isoniazid. This abnormality usually appears in the first 1 to 3 months of treatment but can occur at any time during therapy. In most instances, enzyme levels return to normal, and generally, there is no necessity to discontinue medication during the period of mild serum transaminase elevation. In occasional instances, progressive liver damage occurs, with accompanying symptoms. If the SGOT value exceeds three to five times the upper limit of normal, discontinuation of the isoniazid should be strongly considered. The frequency of progressive liver damage increases with age. It is rare in persons under 20, but occurs in up to 2.3 percent of those over 50 years of age.

Hematologic Reactions:

Agranulocytosis; hemolytic, sideroblastic or aplastic anemia; thrombocytopenia; and eosinophulia.

Hypersensitivity Reactions:

Fever, skin eruptions (morbilliform, maculopapular, purpuric, or exfoliative), lymphadenopathy and vasculitis.

OVERDOSAGE:

Signs and Symptoms:

Isoniazid overdosage produces signs and symptoms within 30 minutes to 3 hours after ingestion. Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, slurring of speech, blurring of vision, and visual hallucinations (including bright colors and strange designs) are among the early manifestations. With marked overdosage, respiratory distress and CNS depression, progressing rapidly from stupor to profound coma, are to be expected, along with severe, intractable seizures. Severe metabolic acidosis, acetonuria and hyperglycemia are typical laboratory findings.

Treatment:

Untreated or inadequately treated cases of gross isoniazid overdosage, 80 mg/kg-150 mg/kg, can cause neurotoxicity6 and terminate fatally, but good response has been reported in most patients brought under adequate treatment within the first few hours after drug ingestion.

For the Asymptomatic Patient:

Absorption of drugs from the GI tract may be decreased by giving activated charcoal. Gastric emptying should also be employed in the asymptomatic patient. Safeguard the patient's airway when employing these procedures. Patients who acutely ingest > 80 mg/kg should be treated with intravenous pyridoxine on a gram per gram basis equal to the isoniazid dose. If an unknown amount of isoniazid is ingested, consider an initial dose of 5 grams of pyridoxine given over 30 to 60 minutes in adults, or 80 mg/kg of pyridoxine in children.

For the Symptomatic Patient:

Ensure adequate ventilation, support cardiac output, and protect the airway while treating seizures and attempting to limit absorption. If the dose of isoniazid is known, the patient should be treated initially with a slow intravenous bolus of pyridoxine, over 3 to 5 minutes, on a gram per gram basis, equal to the isoniazid dose. If the quantity of isoniazid ingestion is unknown, then consider an initial intravenous bolus of pyridoxine of 5 grams in the adult or 80 mg/kg in the child. If seizures continue, the dosage of pyridoxine may be repeated. It would be rare that more than 10 grams of pyridoxine would need to be given. The maximum safe dose for pyridoxine in isoniazid intoxication is not known. If the patient does not respond to pyridoxine, diazepam may be administered. Phenytoin should be used cautiously, because isoniazid interferes with the metabolism of phenytoin.

General:

Obtain blood samples for immediate determination of gases, electrolytes, BUN, glucose, etc.; type and cross-match blood in preparation for possible hemodialysis.

Rapid control of metabolic acidosis:

Patients with this degree of INH intoxication are likely to have hypoventilation. The administration of sodium bicarbonate under these circumstances can cause exacerbation of hypercarbia. Ventilation must be monitored carefully, by measuring blood carbon dioxide levels, and supported mechanically, if there is respiratory insufficiency.

Dialysis:

Both peritoneal and hemodialysis have been used in the management of isoniazid overdosage. These procedures are probably not required if control of seizures and acidosis is achieved with pyridoxine, diazepam and bicarbonate.

Along with measures based on initial and repeated determination of blood gases and other laboratory tests as needed, utilize meticulous respiratory and other intensive care to protect against hypoxia, hypotension, aspiration, pneumonitis, etc.

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION (See also INDICATIONS):

Note – For preventive therapy of tuberculous infection and treatment of tuberculosis, it is recommended that physicians be familiar with the following publications: (1) The recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis, published in the MMWR: vol 42; RR-4, 1993 and (2) Treatment of Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis Infection in Adults and Children, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine: vol 149; 1359-1374, 1994.

For Treatment of Tuberculosis:

Isoniazid is used in conjunction with other effective anti-tuberculous agents. Drug susceptibility testing should be performed on the organisms initially isolated from all patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis. If the bacilli becomes resistant, therapy must be changed to agents to which the bacilli are susceptible.

Usual Oral Dosage (depending on the regimen used):

Adults:

5 mg/kg up to 300 mg daily in a single dose; or 15 mg/kg up to 900 mg/day, two or three times/week.

Children:

10-15 mg/kg up to 300 mg daily in a single dose; or 20-40 mg/kg up to 900 mg/day, two or three times/week.

Patients with Pulmonry Tuberculosis Without HIV Infection:

There are 3 regimen options for the initial treatment of tuberculosis in children and adults:

Option 1: Daily isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide for 8 weeks followed by 16 weeks of isoniazid and rifampin daily or 2-3 times weekly. Ethambutol or streptomycin should be added to the initial regimen until sensitivity to isoniazid and rifampin is demonstrated. The addition of a fourth drug is optional if the relative prevalence of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in the community is less than or equal to four percent.

Option 2: Daily isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin or ethambutol for 2 weeks followed by twice weekly administration of the same drugs for 6 weeks, subsequently twice weekly isoniazid and rifampin for 16 weeks.

Option 3: Three times weekly with isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol or streptomycin for 6 months.

*All regiments given twice weekly or 3 times weekly should be administered by directly observed therapy (see also Directly Observed Therapy (DOT):).

The above treatment guidelines apply only when the disease is caused by organisms that are susceptible to the standard antituberculous agents. Because of the impact of resistance to isoniazid and rifampin on the response to therapy, it is essential that physicians initiating therapy for tuberculosis be familiar with the prevalence of drug resistance in their communities. It is suggested that ethambutol not be used in children whose visual acuity cannot be monitored.

Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis and HIV Infection:

The response of the immunologically impaired host to treatment may not be as satisfactory as that of a person with normal host responsiveness. For this reason, therapeutic decisions for the impaired host must be individualized. Since patients co-infected with HIV may have problems with malabsorption, screening of antimycobacterial drug levels, especially in patients with advanced HIV disease, may be necessary to prevent the emergence of MDRTB.

Patients with Extra pulmonary Tuberculosis:

The basic principles that underlie the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis also apply to Extra pulmonary forms of the disease. Although there have not been the same kinds of carefully conducted controlled trials of treatment of Extra pulmonary tuberculosis as for pulmonary disease, increasing clinical experience indicates that 6 to 9 month short-course regimens are effective. Because of the insufficient data, miliary tuberculosis, bone/joint tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis in infants and children should receive 12 month therapy.

Bacteriologic evaluation of Extra pulmonary tuberculosis may be limited by the relative inaccessibility of the sites of disease. Thus, response to treatment often must be judged on the basis of clinical and radiographic findings.

The use of adjunctive therapies such as surgery and corticosteroids is more commonly required in Extra pulmonary tuberculosis than in pulmonary disease. Surgery may be necessary to obtain specimens for diagnosis and to treat such processes as constrictive pericarditis and spinal cord compression from Pott's Disease. Corticosteroids have been shown to be of benefit in preventing cardiac constriction from tuberculous pericarditis and in decreasing the neurologic sequelae of all stages of tuberculosis meningitis, especially when administered early in the course of the disease.

Pregnant Women with Tuberculosis:

The options listed above must be adjusted for the pregnant patient. Streptomycin interferes with in utero development of the ear and may cause congenital deafness. Routine use of pyrazinamide is also not recommended in pregnancy because of inadequate teratogenicity data. The initial treatment regimen should consist of isoniazid and rifampin. Ethambutol should be included unless primary isoniazid resistance is unlikely (isoniazid resistance rate documented to be less than 4%).

Treatment of Patients with Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (MDRTB):

Multiple-drug resistant tuberculosis (i.e., resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampin) presents difficult treatment problems. Treatment must be individualized and based on susceptibility studies. In such cases, consultation with an expert in tuberculosis is recommended.

Directly Observed Therapy (DOT):

A major cause of drug-resistant tuberculosis is patient non-compliance with treatment. The use of DOT can help assure patient compliance with drug therapy. DOT is the observation of the patient by a health care provider or other responsible person as the patient ingests anti-tuberculosis medications. DOT can be achieved with daily, twice weekly or thrice weekly regimens, and is recommended for all patients.

For Preventative Therapy of Tuberculosis:

Before isoniazid preventive therapy is initiated, bacteriologically positive or radiographically progressive tuberculosis must be excluded. Appropriate evaluations should be performed if Extra pulmonary tuberculosis is suspected.

Adults over 30 Kg: 300 mg per day in a single dose.

Infants and Children: 10 mg/kg (up to 300 mg daily) in a single dose. In situations where adherence with daily preventative therapy cannot be assured, 20-30 mg/kg (not to exceed 900 mg) twice weekly under the direct observation of a health care worker at the time of administration8.

Continuous administration of isoniazid for a sufficient period is an essential part of the regimen because relapse rates are higher if chemotherapy is stopped prematurely. In the treatment of tuberculosis, resistant organisms may multiply and the emergence of resistant organisms during the treatment may necessitate a change in the regimen.

For following patient compliance: the Potts-Cozart test9, a simple colorimetric6 method of checking for isoniazid in the urine, is a useful tool for assuring patient compliance, which is essential for effective tuberculosis control. Additionally, isoniazid test strips are also available to check patient compliance.

Concomitant administration of pyridoxine (B6) is recommended in the malnourished and in those predisposed to neuropathy (e.g., alcoholics and diabetics).

HOW SUPPLIED

Isoniazid Tablets, USP:

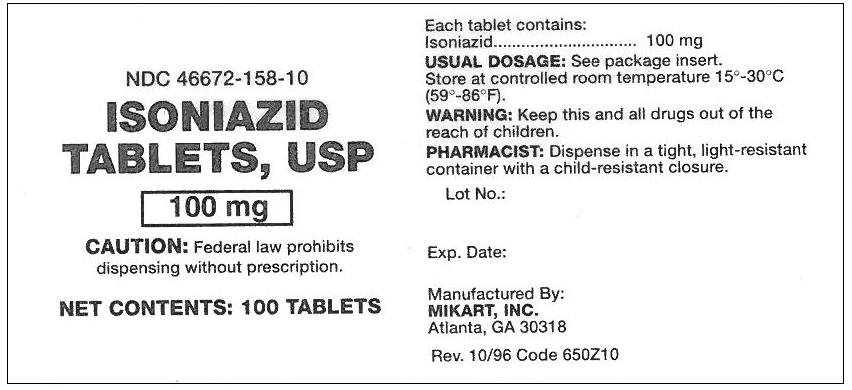

100 mg- round, unscored, white tablet debossed “EFF” on one side and “26” on the other; supplied in bottles of 100, NDC 46672-158-10.

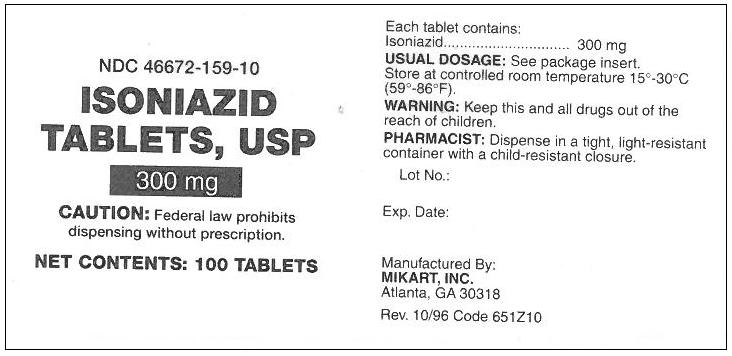

300 mg- round, unscored, white tablet debossed “EFF” on one side and “27” on the other; supplied in bottles of 30, NDC 46672-159-03, bottles of 100, NDC 46672-159-10, and in bottles of 1000, NDC 46672-159-11.

REFERENCES:

- 1.

- Murphy, R., et al: Annuals of Internal Medicine; 1990: November 15; volume 113: 799-800.

- 2.

- Burke, R.F., et al: Res CommunChemPatholPharmacol. 1990: July; vol. 69; 115-118.

- 3.

- Fleenor, M.F., et al: Chest (United States) Letter,; 1991: June; 99 (6): 1554.

- 4.

- Baciewicz, A.M. and Baciewicz, Jr. F.A.,: Arch Int Med 1993, September; volume 153; 1970-1971.

- 5.

- Jonville, A.P., et al: European Journal of Clinical Pharmacol (Germany), 1991: 40 (2) p198.

- 6.

- American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control: Treatment of Tuberculosis and Tuberculous Infection in Adults and Children. Amer. J. Respir Crit Care Med. 1994; 149: p1359-1374.

- 7.

- Hoglund P., et al: European Journal of RespirDis (Denmark) 1987: February; 70 (2) p110-116.

- 8.

- Committee on infectious Diseases American Academy of Pediatrics: 1994, Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases; 23 edition; p487.

- 9.

- Schraufnagel, DE; Testing for Isoniazid; Chest (United States) 1990, August: 98 (2) p314-316.

| ISONIAZID

isoniazid tablet |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| ISONIAZID

isoniazid tablet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Labeler - MIKART, INC. (030034847) |