FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

WARNING: SUICIDALITY AND ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS

Antidepressants increased the risk compared to placebo of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults in short-term studies of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Anyone considering the use of fluoxetine capsulesor any other antidepressant in a child, adolescent, or young adult must balance this risk with the clinical need. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction in risk with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older. Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients of all ages who are started on antidepressant therapy should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. Fluoxetineis approved for use in pediatric patients with MDD and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1) and Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to Boxed Warning section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Major Depressive Disorder

Fluoxetine is indicated for the acute and maintenance treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in adult patients and in pediatric patients aged 8 to18 years [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

The usefulness of the drug in adult and pediatric patients receiving fluoxetine for extended periods should periodically be re-evaluated [see Dosage and Administration (2.1)].

1.2 Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Fluoxetine is indicated for the acute and maintenance treatment of obsessions and compulsions in adult patients and in pediatric patients aged 7 to 17 years with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

The effectiveness of fluoxetine in long-term use, i.e., for more than 13 weeks, has not been systematically evaluated in placebo-controlled trials. Therefore, the physician who elects to use fluoxetine for extended periods, should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient [see Dosage and Administration (2.2)].

1.3 Bulimia Nervosa

Fluoxetine is indicated for the acute and maintenance treatment of binge-eating and vomiting behaviors in adult patients with moderate to severe Bulimia Nervosa [see Clinical Studies (14.3)].

The physician who elects to use fluoxetine for extended periods should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient [see Dosage and Administration (2.3)].

1.4 Panic Disorder

Fluoxetine is indicated for the acute treatment of Panic Disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in adult patients [see Clinical Studies (14.4)].

The effectiveness of fluoxetine in long-term use, i.e., for more than 12 weeks, has not been established in placebo-controlled trials. Therefore, the physician who elects to use fluoxetine for extended periods, should periodically re-evaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug for the individual patient [see Dosage and Administration (2.4)].

1.5 Fluoxetine and Olanzapine in Combination: Depressive Episodes Associated With Bipolar I Disorder

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Clinical Studies section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

Fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination is indicated for the acute treatment of depressive episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder in adult patients.

Fluoxetine monotherapy is not indicated for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder.

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Major Depressive Disorder

Initial Treatment

Adult — In controlled trials used to support the efficacy of fluoxetine, patients were administered morning doses ranging from 20 to 80 mg/day. Studies comparing fluoxetine 20, 40, and 60 mg/day to placebo indicate that 20 mg/day is sufficient to obtain a satisfactory response in Major Depressive Disorder in most cases. Consequently, a dose of 20 mg/day, administered in the morning, is recommended as the initial dose.

A dose increase may be considered after several weeks if insufficient clinical improvement is observed. Doses above 20 mg/day may be administered on a once-a-day (morning) or BID schedule (i.e., morning and noon) and should not exceed a maximum dose of 80 mg/day.

Pediatric (children and adolescents) — In the short-term (8 to 9 week) controlled clinical trials of fluoxetine supporting its effectiveness in the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder, patients were administered fluoxetine doses of 10 to 20 mg/day [see Clinical Studies (14.1)]. Treatment should be initiated with a dose of 10 or 20 mg/day. After 1 week at 10 mg/day, the dose should be increased to 20 mg/day.

However, due to higher plasma levels in lower weight children, the starting and target dose in this group may be 10 mg/day. A dose increase to 20 mg/day may be considered after several weeks if insufficient clinical improvement is observed.

All patients — As with other drugs effective in the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder, the full effect may be delayed until 4 weeks of treatment or longer.

Maintenance/Continuation/Extended Treatment — It is generally agreed that acute episodes of Major Depressive Disorder require several months or longer of sustained pharmacologic therapy. Whether the dose needed to induce remission is identical to the dose needed to maintain and/or sustain euthymia is unknown.

Daily Dosing — Systematic evaluation of fluoxetine in adult patients has shown that its efficacy in Major Depressive Disorder is maintained for periods of up to 38 weeks following 12 weeks of open-label acute treatment (50 weeks total) at a dose of 20 mg/day [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

Switching Patients to a Tricyclic Antidepressant (TCA) — Dosage of a TCA may need to be reduced, and plasma TCA concentrations may need to be monitored temporarily when fluoxetine is coadministered or has been recently discontinued [see Drug Interactions (7.9)].

Switching Patients to or From a Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor (MAOI) — At least 14 days should elapse between discontinuation of an MAOI and initiation of therapy with fluoxetine. In addition, at least 5 weeks, perhaps longer, should be allowed after stopping fluoxetine before starting an MAOI [see Contraindications (4) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

2.2 Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Initial Treatment

Adult — In the controlled clinical trials of fluoxetine supporting its effectiveness in the treatment of OCD, patients were administered fixed daily doses of 20, 40, or 60 mg of fluoxetine or placebo [see Clinical Studies (14.2)]. In one of these studies, no dose-response relationship for effectiveness was demonstrated. Consequently, a dose of 20 mg/day, administered in the morning, is recommended as the initial dose. Since there was a suggestion of a possible dose-response relationship for effectiveness in the second study, a dose increase may be considered after several weeks if insufficient clinical improvement is observed. The full therapeutic effect may be delayed until 5 weeks of treatment or longer.

Doses above 20 mg/day may be administered on a once daily (i.e., morning) or BID schedule (i.e., morning and noon). A dose range of 20 to 60 mg/day is recommended; however, doses of up to 80 mg/day have been well tolerated in open studies of OCD. The maximum fluoxetine dose should not exceed 80 mg/day.

Pediatric (children and adolescents) — In the controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine supporting its effectiveness in the treatment of OCD, patients were administered fluoxetine doses in the range of 10 to 60 mg/day [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

In adolescents and higher weight children, treatment should be initiated with a dose of 10 mg/day. After 2 weeks, the dose should be increased to 20 mg/day. Additional dose increases may be considered after several more weeks if insufficient clinical improvement is observed. A dose range of 20 to 60 mg/day is recommended.

In lower weight children, treatment should be initiated with a dose of 10 mg/day. Additional dose increases may be considered after several more weeks if insufficient clinical improvement is observed. A dose range of 20 to 30 mg/day is recommended. Experience with daily doses greater than 20 mg is very minimal, and there is no experience with doses greater than 60 mg.Maintenance/Continuation Treatment — While there are no systematic studies that answer the question of how long to continue fluoxetine, OCD is a chronic condition and it is reasonable to consider continuation for a responding patient. Although the efficacy of fluoxetine after 13 weeks has not been documented in controlled trials, adult patients have been continued in therapy under double-blind conditions for up to an additional 6 months without loss of benefit. However, dosage adjustments should be made to maintain the patient on the lowest effective dosage, and patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for treatment.

2.3 Bulimia Nervosa

Initial Treatment — In the controlled clinical trials of fluoxetine supporting its effectiveness in the treatment of Bulimia Nervosa, patients were administered fixed daily fluoxetine doses of 20 or 60 mg, or placebo [see Clinical Studies (14.3)]. Only the 60 mg dose was statistically significantly superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and vomiting. Consequently, the recommended dose is 60 mg/day, administered in the morning. For some patients it may be advisable to titrate up to this target dose over several days. Fluoxetine doses above 60 mg/day have not been systematically studied in patients with bulimia.

Maintenance/Continuation Treatment — Systematic evaluation of continuing fluoxetine 60 mg/day for periods of up to 52 weeks in patients with bulimia who have responded while taking fluoxetine 60 mg/day during an 8 week acute treatment phase has demonstrated a benefit of such maintenance treatment [see Clinical Studies (14.3)]. Nevertheless, patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment.

2.4 Panic Disorder

Initial Treatment — In the controlled clinical trials of fluoxetine supporting its effectiveness in the treatment of Panic Disorder, patients were administered fluoxetine doses in the range of 10 to 60 mg/day [see Clinical Studies (14.4)]. Treatment should be initiated with a dose of 10 mg/day. After one week, the dose should be increased to 20 mg/day. The most frequently administered dose in the 2 flexible-dose clinical trials was 20 mg/day.

A dose increase may be considered after several weeks if no clinical improvement is observed. Fluoxetine doses above 60 mg/day have not been systematically evaluated in patients with Panic Disorder.

Maintenance/Continuation Treatment — While there are no systematic studies that answer the question of how long to continue fluoxetine, panic disorder is a chronic condition and it is reasonable to consider continuation for a responding patient. Nevertheless, patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for continued treatment.

2.5 Fluoxetine and Olanzapine in Combination: Depressive Episodes Associated With Bipolar I Disorder

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Clinical Studies section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

Fluoxetine should be administered in combination with oral olanzapine once daily in the evening, without regard to meals, generally beginning with 5 mg of oral olanzapine and 20 mg of fluoxetine. Dosage adjustments, if indicated, can be made according to efficacy and tolerability within dose ranges of fluoxetine 20 to 50 mg and oral olanzapine 5 to 12.5 mg. Antidepressant efficacy was demonstrated with olanzapine and fluoxetine in combination with a dose range of olanzapine 6 to 12 mg and fluoxetine 25 to 50 mg.

Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine in combination with olanzapine was determined in clinical trials supporting approval of olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules (fixed-dose combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine). Olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules are dosed between 3 mg/25 mg (olanzapine/fluoxetine) per day and 12 mg/50 mg (olanzapine/fluoxetine) per day. The following table demonstrates the appropriate individual component doses of fluoxetine and olanzapine versus olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules. Dosage adjustments, if indicated, should be made with the individual components according to efficacy and tolerability.

|

||

| For Olanzapine and Fluoxetine Hydrochloride Capsules(mg/day) | Use in Combination | |

| Olanzapine (mg/day) | Fluoxetine (mg/day) | |

| 3 mg olanzapine/25 mg fluoxetine | 2.5 | 20 |

| 6 mg olanzapine/25 mg fluoxetine | 5 | 20 |

| 12 mg olanzapine/25 mg fluoxetine | 10 + 2.5 | 20 |

| 6 mg olanzapine/50 mg fluoxetine | 5 | 40 + 10 |

| 12 mg olanzapine/50 mg fluoxetine | 10 + 2.5 | 40 + 10 |

While there is no body of evidence to answer the question of how long a patient treated with fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination should remain on it, it is generally accepted that Bipolar I Disorder, including the depressive episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder, is a chronic illness requiring chronic treatment. The physician should periodically re-examine the need for continued pharmacotherapy.

Safety of coadministration of doses above 18 mg olanzapine with 75 mg fluoxetine has not been evaluated in clinical studies.

Fluoxetine monotherapy is not indicated for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder.

2.7 Dosing in Specific Populations

Treatment of pregnant Women During the Third Trimester — When treating pregnant women with fluoxetine during the third trimester, the physician should carefully consider the potential risks and potential benefits of treatment. Neonates exposed to SNRIs or SSRIs late in the third trimester have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding. The physician may consider tapering fluoxetine in the third trimester [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

Geriatric — A lower or less frequent dosage should be considered for the elderly [see Use in Specific Populations (8.5)].

Hepatic Impairment — As with many other medications, a lower or less frequent dosage should be used in patients with hepatic impairment [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.4) and Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

Concomitant Illness — Patients with concurrent disease or on multiple concomitant medications may require dosage adjustments [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.4) and Warnings and Precautions (5.10)].

Fluoxetine and Olanzapine in Combination – The starting dose of oral olanzapine 2.5 to 5 mg with fluoxetine 20 mg should be used for patients with a predisposition to hypotensive reactions, patients with hepatic impairment, or patients who exhibit a combination of factors that may slow the metabolism of olanzapine or fluoxetine in combination (female gender, geriatric age, nonsmoking status), or those patients who may be pharmacodynamically sensitive to olanzapine. Dosing modifications may be necessary in patients who exhibit a combination of factors that may slow metabolism. When indicated, dose escalation should be performed with caution in these patients. Fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination have not been systematically studied in patients over 65 years of age or in patients less than 18 years of age [see Warnings and Precautions (5.14) and Drug Interactions (7.9)].

2.8 Discontinuation of Treatment

Symptoms associated with discontinuation of fluoxetine, SNRIs, and SSRIs, have been reported [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)].

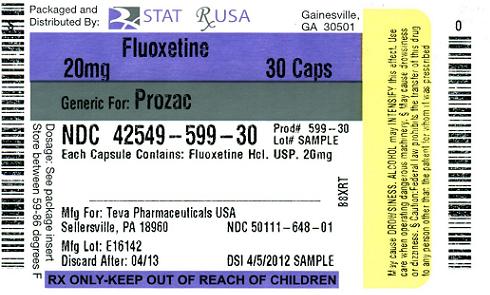

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Fluoxetine Capsules USP, 10 mg contain fluoxetine hydrochloride, equivalent to 10 mg fluoxetine, and are available as white, opaque capsules printed with PLIVA 647 in green band on cap and body.

Fluoxetine Capsules USP, 20 mg contain fluoxetine hydrochloride, equivalent to 20 mg fluoxetine, and are available as white, opaque capsules printed with PLIVA 648 in green band on cap only.

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Contraindications section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

The use of fluoxetine is contraindicated with the following:

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Warnings and Precautions section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

5.1 Clinical Worsening and Suicide Risk

Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications, and this risk may persist until significant remission occurs. Suicide is a known risk of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, and these disorders themselves are the strongest predictors of suicide. There has been a long-standing concern, however, that antidepressants may have a role in inducing worsening of depression and the emergence of suicidality in certain patients during the early phases of treatment. Pooled analyses of short-term placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and others) showed that these drugs increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (suicidality) in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18 to 24) with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24; there was a reduction with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults aged 65 and older.

The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in children and adolescents with MDD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 24 short-term trials of 9 antidepressant drugs in over 4400 patients. The pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials in adults with MDD or other psychiatric disorders included a total of 295 short-term trials (median duration of 2 months) of 11 antidepressant drugs in over 77,000 patients. There was considerable variation in risk of suicidality among drugs, but a tendency toward an increase in the younger patients for almost all drugs studied. There were differences in absolute risk of suicidality across the different indications, with the highest incidence in MDD. The risk differences (drug versus placebo), however, were relatively stable within age strata and across indications. These risk differences (drug-placebo difference in the number of cases of suicidality per 1000 patients treated) are provided in Table 2.

| Age Range | Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Cases of Suicidality per 1000 Patients Treated |

| Increases Compared to Placebo | |

| < 18 | 14 additional cases |

| 18 to 24 | 5 additional cases |

| Decreases Compared to Placebo | |

| 25 to 64 | 1 fewer case |

| ≥ 65 | 6 fewer cases |

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric trials. There were suicides in the adult trials, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about drug effect on suicide.

It is unknown whether the suicidality risk extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond several months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with depression that the use of antidepressants can delay the recurrence of depression.

All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases.

The following symptoms, anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania, have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants for Major Depressive Disorder as well as for other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric. Although a causal link between the emergence of such symptoms and either the worsening of depression and/or the emergence of suicidal impulses has not been established, there is concern that such symptoms may represent precursors to emerging suicidality.

Consideration should be given to changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing the medication, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidality or symptoms that might be precursors to worsening depression or suicidality, especially if these symptoms are severe, abrupt in onset, or were not part of the patient’s presenting symptoms.

If the decision has been made to discontinue treatment, medication should be tapered, as rapidly as is feasible, but with recognition that abrupt discontinuation can be associated with certain symptoms [see Warnings and Precautions (5.13)].

Families and caregivers of patients being treated with antidepressants for Major Depressive Disorder or other indications, both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric, should be alerted about the need to monitor patients for the emergence of agitation, irritability, unusual changes in behavior, and the other symptoms described above, as well as the emergence of suicidality, and to report such symptoms immediately to health care providers. Such monitoring should include daily observation by families and caregivers. Prescriptions for fluoxetine capsules should be written for the smallest quantity of capsules consistent with good patient management, in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

It should be noted that fluoxetine is approved in the pediatric population only for Major Depressive Disorder and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Safety and effectiveness of fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination in patients less than 18 years of age have not been established.

5.2 Serotonin Syndrome or Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)-Like Reactions

The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)-like reactions have been reported with SNRIs and SSRIs alone, including fluoxetine treatment, but particularly with concomitant use of serotonergic drugs (including triptans) with drugs which impair metabolism of serotonin (including MAOIs), or with antipsychotics or other dopamine antagonists. Serotonin syndrome symptoms may include mental status changes (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, hyperthermia), neuromuscular aberrations (e.g., hyperreflexia, incoordination) and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Serotonin syndrome, in its most severe form can resemble neuroleptic malignant syndrome, which includes hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability with possible rapid fluctuation of vital signs, and mental status changes. Patients should be monitored for the emergence of serotonin syndrome or NMS-like signs and symptoms.

The concomitant use of fluoxetine with MAOIs intended to treat depression is contraindicated [see Contraindications (4) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

If concomitant treatment of fluoxetine with a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor agonist (triptan) is clinically warranted, careful observation of the patient is advised, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases [see Drug Interactions (7.4)].

The concomitant use of fluoxetine with serotonin precursors (such as tryptophan) is not recommended [see Drug Interactions (7.3)].

Treatment with fluoxetine and any concomitant serotonergic or antidopaminergic agents, including antipsychotics, should be discontinued immediately if the above reactions occur, and supportive symptomatic treatment should be initiated.

5.3 Allergic Reactions and Rash

In U.S. fluoxetine clinical trials, 7% of 10,782 patients developed various types of rashes and/or urticaria. Among the cases of rash and/or urticaria reported in premarketing clinical trials, almost a third were withdrawn from treatment because of the rash and/or systemic signs or symptoms associated with the rash. Clinical findings reported in association with rash include fever, leukocytosis, arthralgias, edema, carpal tunnel syndrome, respiratory distress, lymphadenopathy, proteinuria, and mild transaminase elevation. Most patients improved promptly with discontinuation of fluoxetine and/or adjunctive treatment with antihistamines or steroids, and all patients experiencing these reactions were reported to recover completely.

In premarketing clinical trials, 2 patients are known to have developed a serious cutaneous systemic illness. In neither patient was there an unequivocal diagnosis, but one was considered to have a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and the other, a severe desquamating syndrome that was considered variously to be a vasculitis or erythema multiforme. Other patients have had systemic syndromes suggestive of serum sickness.

Since the introduction of fluoxetine, systemic reactions, possibly related to vasculitis and including lupus-like syndrome, have developed in patients with rash. Although these reactions are rare, they may be serious, involving the lung, kidney, or liver. Death has been reported to occur in association with these systemic reactions.

Anaphylactoid reactions, including bronchospasm, angioedema, laryngospasm, and urticaria alone and in combination, have been reported.

Pulmonary reactions, including inflammatory processes of varying histopathology and/or fibrosis, have been reported rarely. These reactions have occurred with dyspnea as the only preceding symptom.

Whether these systemic reactions and rash have a common underlying cause or are due to different etiologies or pathogenic processes is not known. Furthermore, a specific underlying immunologic basis for these reactions has not been identified. Upon the appearance of rash or of other possibly allergic phenomena for which an alternative etiology cannot be identified, fluoxetine should be discontinued.

5.4 Screening Patients for Bipolar Disorder and Monitoring for Mania/Hypomania

A major depressive episode may be the initial presentation of Bipolar Disorder. It is generally believed (though not established in controlled trials) that treating such an episode with an antidepressant alone may increase the likelihood of precipitation of a mixed/manic episode in patients at risk for Bipolar Disorder. Whether any of the symptoms described for clinical worsening and suicide risk represent such a conversion is unknown. However, prior to initiating treatment with an antidepressant, patients with depressive symptoms should be adequately screened to determine if they are at risk for Bipolar Disorder; such screening should include a detailed psychiatric history, including a family history of suicide, Bipolar Disorder, and depression. It should be noted that fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination is approved for the acute treatment of depressive episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder [see Warnings and Precautions section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules]. Fluoxetine monotherapy is not indicated for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder.

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for Major Depressive Disorder, mania/hypomania was reported in 0.1% of patients treated with fluoxetine and 0.1% of patients treated with placebo. Activation of mania/hypomania has also been reported in a small proportion of patients with Major Affective Disorder treated with other marketed drugs effective in the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for OCD, mania/hypomania was reported in 0.8% of patients treated with fluoxetine and no patients treated with placebo. No patients reported mania/hypomania in U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for bulimia. In U.S. fluoxetine clinical trials, 0.7% of 10,782 patients reported mania/hypomania [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

5.5 Seizures

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for Major Depressive Disorder, convulsions (or reactions described as possibly having been seizures) were reported in 0.1% of patients treated with fluoxetine and 0.2% of patients treated with placebo. No patients reported convulsions in U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for either OCD or bulimia. In U.S. fluoxetine clinical trials, 0.2% of 10,782 patients reported convulsions. The percentage appears to be similar to that associated with other marketed drugs effective in the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Fluoxetine should be introduced with care in patients with a history of seizures.

5.6 Altered Appetite and Weight

Significant weight loss, especially in underweight depressed or bulimic patients, may be an undesirable result of treatment with fluoxetine.

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for Major Depressive Disorder, 11% of patients treated with fluoxetine and 2% of patients treated with placebo reported anorexia (decreased appetite). Weight loss was reported in 1.4% of patients treated with fluoxetine and in 0.5% of patients treated with placebo. However, only rarely have patients discontinued treatment with fluoxetine because of anorexia or weight loss [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for OCD, 17% of patients treated with fluoxetine and 10% of patients treated with placebo reported anorexia (decreased appetite). One patient discontinued treatment with fluoxetine because of anorexia [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for Bulimia Nervosa, 8% of patients treated with fluoxetine 60 mg and 4% of patients treated with placebo reported anorexia (decreased appetite). Patients treated with fluoxetine 60 mg on average lost 0.45 kg compared with a gain of 0.16 kg by patients treated with placebo in the 16 week double-blind trial. Weight change should be monitored during therapy.

5.7 Abnormal Bleeding

SNRIs and SSRIs, including fluoxetine, may increase the risk of bleeding reactions. Concomitant use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin, and other anti-coagulants may add to this risk. Case reports and epidemiological studies (case-control and cohort design) have demonstrated an association between use of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding reactions related to SNRIs and SSRIs use have ranged from ecchymoses, hematomas, epistaxis, and petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages. Patients should be cautioned about the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of fluoxetine and NSAIDs, aspirin, warfarin, or other drugs that affect coagulation [see Drug Interactions (7.6)].

5.8 Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia has been reported during treatment with SNRIs and SSRIs, including fluoxetine. In many cases, this hyponatremia appears to be the result of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). Cases with serum sodium lower than 110 mmol/L have been reported and appeared to be reversible when fluoxetine was discontinued. Elderly patients may be at greater risk of developing hyponatremia with SNRIs and SSRIs. Also, patients taking diuretics or who are otherwise volume depleted may be at greater risk [see Use in Specific Populations (8.5)]. Discontinuation of fluoxetine should be considered in patients with symptomatic hyponatremia and appropriate medical intervention should be instituted.

Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia include headache, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, confusion, weakness, and unsteadiness, which may lead to falls. More severe and/or acute cases have been associated with hallucination, syncope, seizure, coma, respiratory arrest, and death.

5.9 Anxiety and Insomnia

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for Major Depressive Disorder, 12% to 16% of patients treated with fluoxetine and 7% to 9% of patients treated with placebo reported anxiety, nervousness, or insomnia.

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for OCD, insomnia was reported in 28% of patients treated with fluoxetine and in 22% of patients treated with placebo. Anxiety was reported in 14% of patients treated with fluoxetine and in 7% of patients treated with placebo.

In U.S. placebo-controlled clinical trials for Bulimia Nervosa, insomnia was reported in 33% of patients treated with fluoxetine 60 mg, and 13% of patients treated with placebo. Anxiety and nervousness were reported, respectively, in 15% and 11% of patients treated with fluoxetine 60 mg and in 9% and 5% of patients treated with placebo.

Among the most common adverse reactions associated with discontinuation (incidence at least twice that for placebo and at least 1% for fluoxetine in clinical trials collecting only a primary reaction associated with discontinuation) in U.S. placebo-controlled fluoxetine clinical trials were anxiety (2% in OCD), insomnia (1% in combined indications and 2% in bulimia), and nervousness (1% in Major Depressive Disorder) [see Table 5].

5.10 Use in Patients With Concomitant Illness

Clinical experience with fluoxetine in patients with concomitant systemic illness is limited. Caution is advisable in using fluoxetine in patients with diseases or conditions that could affect metabolism or hemodynamic responses.

Cardiovascular — Fluoxetine has not been evaluated or used to any appreciable extent in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable heart disease. Patients with these diagnoses were systematically excluded from clinical studies during the product’s premarket testing. However, the electrocardiograms of 312 patients who received fluoxetine in double-blind trials were retrospectively evaluated; no conduction abnormalities that resulted in heart block were observed. The mean heart rate was reduced by approximately 3 beats/min.

Glycemic Control — In patients with diabetes, fluoxetine may alter glycemic control. Hypoglycemia has occurred during therapy with fluoxetine, and hyperglycemia has developed following discontinuation of the drug. As is true with many other types of medication when taken concurrently by patients with diabetes, insulin and/or oral hypoglycemic, dosage may need to be adjusted when therapy with fluoxetine is instituted or discontinued.

Acute Narrow-Angle Glaucoma — Mydriasis has been reported in association with fluoxetine; therefore, caution should be used when prescribing fluoxetine in patients with raised intraocular pressure or those at risk of acute narrow-angle glaucoma.

5.11 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

As with any CNS-active drug, fluoxetine has the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills. Patients should be cautioned about operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are reasonably certain that the drug treatment does not affect them adversely.

5.12 Long Elimination Half-Life

Because of the long elimination half-lives of the parent drug and its major active metabolite, changes in dose will not be fully reflected in plasma for several weeks, affecting both strategies for titration to final dose and withdrawal from treatment. This is of potential consequence when drug discontinuation is required or when drugs are prescribed that might interact with fluoxetine and norfluoxetine following the discontinuation of fluoxetine [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

5.13 Discontinuation of Treatment

During marketing of fluoxetine, SNRIs, and SSRIs, there have been spontaneous reports of adverse reactions occurring upon discontinuation of these drugs, particularly when abrupt, including the following: dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesias such as electric shock sensations), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, and hypomania. While these reactions are generally self-limiting, there have been reports of serious discontinuation symptoms. Patients should be monitored for these symptoms when discontinuing treatment with fluoxetine. A gradual reduction in the dose rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate. Plasma fluoxetine and norfluoxetine concentration decrease gradually at the conclusion of therapy which may minimize the risk of discontinuation symptoms with this drug.

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Adverse Reactions section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect or predict the rates observed in practice.

Multiple doses of fluoxetine have been administered to 10,782 patients with various diagnoses in U.S. clinical trials. In addition, there have been 425 patients administered fluoxetine in panic clinical trials. Adverse reactions were recorded by clinical investigators using descriptive terminology of their own choosing. Consequently, it is not possible to provide a meaningful estimate of the proportion of individuals experiencing adverse reactions without first grouping similar types of reactions into a limited (i.e., reduced) number of standardized reaction categories.

In the tables and tabulations that follow, COSTART Dictionary terminology has been used to classify reported adverse reactions. The stated frequencies represent the proportion of individuals who experienced, at least once, a treatment-emergent adverse reaction of the type listed. A reaction was considered treatment-emergent if it occurred for the first time or worsened while receiving therapy following baseline evaluation. It is important to emphasize that reactions reported during therapy were not necessarily caused by it.

The prescriber should be aware that the figures in the tables and tabulations cannot be used to predict the incidence of side effects in the course of usual medical practice where patient characteristics and other factors differ from those that prevailed in the clinical trials. Similarly, the cited frequencies cannot be compared with figures obtained from other clinical investigations involving different treatments, uses, and investigators. The cited figures, however, do provide the prescribing physician with some basis for estimating the relative contribution of drug and nondrug factors to the side effect incidence rate in the population studied.

Incidence in Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, bulimia, and Panic Disorder placebo-controlled clinical trials (excluding data from extensions of trials) — Table 3 enumerates the most common treatment-emergent adverse reactions associated with the use of fluoxetine (incidence of at least 5% for fluoxetine and at least twice that for placebo within at least 1 of the indications) for the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, and bulimia in U.S. controlled clinical trials and Panic Disorder in U.S. plus non-U.S. controlled trials. Table 5 enumerates treatment-emergent adverse reactions that occurred in 2% or more patients treated with fluoxetine and with incidence greater than placebo who participated in U.S. Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, and bulimia controlled clinical trials and U.S. plus non-U.S. Panic Disorder controlled clinical trials. Table 4 provides combined data for the pool of studies that are provided separately by indication in Table 3.

|

||||||||

| Percentage of Patients Reporting Event | ||||||||

| Major Depressive Disorder | OCD | Bulimia | Panic Disorder | |||||

| Body System/ Adverse Reaction | Fluoxetine (N = 1728) | Placebo (N = 975) | Fluoxetine (N = 266) | Placebo (N = 89) | Fluoxetine (N = 450) | Placebo (N = 267) | Fluoxetine (N = 425) | Placebo (N = 342) |

| Body as a Whole | ||||||||

| Asthenia | 9 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 21 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Flu syndrome | 3 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Cardiovascular System | ||||||||

| Vasodilatation | 3 | 2 | 5 | -- | 2 | 1 | 1 | -- |

| Digestive System | ||||||||

| Nausea | 21 | 9 | 26 | 13 | 29 | 11 | 12 | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 12 | 8 | 18 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 4 |

| Anorexia | 11 | 2 | 17 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Dry mouth | 10 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Dyspepsia | 7 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| Nervous System | ||||||||

| Insomnia | 16 | 9 | 28 | 22 | 33 | 13 | 10 | 7 |

| Anxiety | 12 | 7 | 14 | 7 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 2 |

| Nervousness | 14 | 9 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Somnolence | 13 | 6 | 17 | 7 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 2 |

| Tremor | 10 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

|

Libido decreased | 3 | -- | 11 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

|

Abnormal dreams | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Respiratory System | ||||||||

| Pharyngitis | 3 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Sinusitis | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Yawn | -- | -- | 7 | -- | 11 | -- | 1 | -- |

| Skin and Appendages | ||||||||

| Sweating | 8 | 3 | 7 | -- | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Rash | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Urogenital System | ||||||||

| Impotence ‡ | 2 | -- | -- | -- | 7 | -- | 1 | -- |

|

Abnormal ejaculation ‡ | -- | -- | 7 | -- | 7 | -- | 2 | 1 |

| Percentage of Patients Reporting Event | ||

| Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, Bulimia, and Panic Disorder Combined | ||

| Body System/Adverse Reaction | Fluoxetine (N = 2869) | Placebo (N = 1673) |

| Body as a Whole | ||

| Headache | 21 | 19 |

| Asthenia | 11 | 6 |

| Flu syndrome | 5 | 4 |

| Fever | 2 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular System | ||

| Vasodilatation | 2 | 1 |

| Digestive System | ||

| Nausea | 22 | 9 |

| Diarrhea | 11 | 7 |

| Anorexia | 10 | 3 |

| Dry mouth | 9 | 6 |

| Dyspepsia | 8 | 4 |

| Constipation | 5 | 4 |

| Flatulence | 3 | 2 |

| Vomiting | 3 | 2 |

|

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders | ||

| Weight loss | 2 | 1 |

| Nervous System | ||

| Insomnia | 19 | 10 |

| Nervousness | 13 | 8 |

| Anxiety | 12 | 6 |

| Somnolence | 12 | 5 |

| Dizziness | 9 | 6 |

| Tremor | 9 | 2 |

| Libido decreased | 4 | 1 |

| Thinking abnormal | 2 | 1 |

| Respiratory System | ||

| Yawn | 3 | -- |

| Skin and Appendages | ||

| Sweating | 7 | 3 |

| Rash | 4 | 3 |

| Pruritus | 3 | 2 |

| Special Senses | ||

| Abnormal vision | 2 | 1 |

Associated with discontinuation in Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, bulimia, and Panic Disorder placebo-controlled clinical trials (excluding data from extensions of trials) — Table 5 lists the adverse reactions associated with discontinuation of fluoxetine treatment (incidence at least twice that for placebo and at least 1% for fluoxetine in clinical trials collecting only a primary reaction associated with discontinuation) in Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, bulimia, and Panic Disorder clinical trials, plus non-U.S. Panic Disorder clinical trials.

|

||||

| Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, Bulimia, and Panic Disorder Combined (N = 1533) |

Major Depressive Disorder (N = 392) |

OCD (N = 266) |

Bulimia (N = 450) |

Panic Disorder (N = 425) |

| Anxiety (1%) | -- | Anxiety (2%) | -- | Anxiety (2%) |

| -- | -- | -- | Insomnia (2%) | -- |

| -- | Nervousness (1%) | -- | -- | Nervousness (1%) |

| -- | -- | Rash (1%) | -- | -- |

Other adverse reactions in pediatric patients (children and adolescents) — Treatment-emergent adverse reactions were collected in 322 pediatric patients (180 fluoxetine-treated, 142 placebo-treated). The overall profile of adverse reactions was generally similar to that seen in adult studies, as shown in Tables 4 and 5. However, the following adverse reactions (excluding those which appear in the body or footnotes of Tables 4 and 5 and those for which the COSTART terms were uninformative or misleading) were reported at an incidence of at least 2% for fluoxetine and greater than placebo: thirst, hyperkinesia, agitation, personality disorder, epistaxis, urinary frequency, and menorrhagia.

The most common adverse reaction (incidence at least 1% for fluoxetine and greater than placebo) associated with discontinuation in 3 pediatric placebo-controlled trials (N = 418 randomized; 228 fluoxetine-treated; 190 placebo-treated) was mania/hypomania (1.8% for fluoxetine-treated, 0% for placebo-treated). In these clinical trials, only a primary reaction associated with discontinuation was collected.

Male and female sexual dysfunction with SSRIs — Although changes in sexual desire, sexual performance, and sexual satisfaction often occur as manifestations of a psychiatric disorder, they may also be a consequence of pharmacologic treatment. In particular, some evidence suggests that SSRIs can cause such untoward sexual experiences. Reliable estimates of the incidence and severity of untoward experiences involving sexual desire, performance, and satisfaction are difficult to obtain, however, in part because patients and physicians may be reluctant to discuss them. Accordingly, estimates of the incidence of untoward sexual experience and performance, cited in product labeling, are likely to underestimate their actual incidence. In patients enrolled in U.S. Major Depressive Disorder, OCD, and bulimia placebo-controlled clinical trials, decreased libido was the only sexual side effect reported by at least 2% of patients taking fluoxetine (4% fluoxetine, < 1% placebo). There have been spontaneous reports in women taking fluoxetine of orgasmic dysfunction, including anorgasmia.

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies examining sexual dysfunction with fluoxetine treatment.

Symptoms of sexual dysfunction occasionally persist after discontinuation of fluoxetine treatment.

Priapism has been reported with all SSRIs.

While it is difficult to know the precise risk of sexual dysfunction associated with the use of SSRIs, physicians should routinely inquire about such possible side effects.

6.2 Other Reactions

Following is a list of treatment-emergent adverse reactions reported by patients treated with fluoxetine in clinical trials. This listing is not intended to include reactions (1) already listed in previous tables or elsewhere in labeling, (2) for which a drug cause was remote, (3) which were so general as to be uninformative, (4) which were not considered to have significant clinical implications, or (5) which occurred at a rate equal to or less than placebo.

Reactions are classified by body system using the following definitions: frequent adverse reactions are those occurring in at least 1/100 patients; infrequent adverse reactions are those occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients; rare reactions are those occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients.

Body as a Whole — Frequent: chills; Infrequent: suicide attempt; Rare: acute abdominal syndrome, photosensitivity reaction.

Cardiovascular System — Frequent: palpitation; Infrequent: arrhythmia, hypotension1.

Digestive System — Infrequent: dysphagia, gastritis, gastroenteritis, melena, stomach ulcer; Rare: bloody diarrhea, duodenal ulcer, esophageal ulcer, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hematemesis, hepatitis, peptic ulcer, stomach ulcer hemorrhage.

Hemic and Lymphatic System — Infrequent: ecchymosis; Rare: petechia, purpura.

Nervous System — Frequent: emotional lability; Infrequent: akathisia, ataxia, balance disorder1, bruxism1, buccoglossal syndrome, depersonalization, euphoria, hypertonia, libido increased, myoclonus, paranoid reaction; Rare: delusions.

Respiratory System — Rare: larynx edema.

Skin and Appendages — Infrequent: alopecia; Rare: purpuric rash.

Special Senses — Frequent: taste perversion; Infrequent: mydriasis.

Urogenital System — Frequent: micturition disorder; Infrequent: dysuria, gynecological bleeding2 .

1 MedDRA dictionary term from integrated database of placebo controlled trials of 15,870 patients, of which 9673 patients received fluoxetine.

2 Group term that includes individual MedDRA terms: cervix hemorrhage uterine, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, genital hemorrhage, menometrorrhagia, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, polymenorrhea, postmenopausal hemorrhage, uterine hemorrhage, vaginal hemorrhage. Adjusted for gender.

6.3 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post approval use of fluoxetine. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is difficult to reliably estimate their frequency or evaluate a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Voluntary reports of adverse reactions temporally associated with fluoxetine that have been received since market introduction and that may have no causal relationship with the drug include the following: aplastic anemia, atrial fibrillation1, cataract, cerebrovascular accident1, cholestatic jaundice, dyskinesia (including, for example, a case of buccal-lingual-masticatory syndrome with involuntary tongue protrusion reported to develop in a 77-year-old female after 5 weeks of fluoxetine therapy and which completely resolved over the next few months following drug discontinuation), eosinophilic pneumonia1, epidermal necrolysis, erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, exfoliative dermatitis, gynecomastia, heart arrest1, hepatic failure/necrosis, hyperprolactinemia, hypoglycemia, immune-related hemolytic anemia, kidney failure, memory impairment, movement disorders developing in patients with risk factors including drugs associated with such reactions and worsening of preexisting movement disorders, optic neuritis, pancreatitis1, pancytopenia, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, QT prolongation, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, thrombocytopenia1, thrombocytopenic purpura, ventricular tachycardia (including torsade de pointes–type arrhythmias), vaginal bleeding, and violent behaviors1.

1 These terms represent serious adverse events, but do not meet the definition for adverse drug reactions.

They are included here because of their seriousness.

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

As with all drugs, the potential for interaction by a variety of mechanisms (e.g., pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic drug inhibition or enhancement, etc.) is a possibility.

7.1 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOI)

There have been reports of serious, sometimes fatal, reactions (including hyperthermia, rigidity, myoclonus, autonomic instability with possible rapid fluctuations of vital signs, and mental status changes that include extreme agitation progressing to delirium and coma) in patients receiving fluoxetine in combination with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), and in patients who have recently discontinued fluoxetine and are then started on an MAOI. Some cases presented with features resembling neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Therefore, fluoxetine should not be used in combination with an MAOI, or within a minimum of 14 days of discontinuing therapy with an MAOI [see Contraindications (4)]. Since fluoxetine and its major metabolite have very long elimination half-lives, at least 5 weeks (perhaps longer, especially if fluoxetine has been prescribed chronically and/or at higher doses) should be allowed after stopping fluoxetine before starting an MAOI [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.2 CNS Acting Drugs

Caution is advised if the concomitant administration of fluoxetine and such drugs is required. In evaluating individual cases, consideration should be given to using lower initial doses of the concomitantly administered drugs, using conservative titration schedules, and monitoring of clinical status [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.3 Serotonergic Drugs

Based on the mechanism of action of SNRIs and SSRIs, including fluoxetine, and the potential for serotonin syndrome, caution is advised when fluoxetine is coadministered with other drugs that may affect the serotonergic neurotransmitter systems, such as triptans, linezolid (an antibiotic which is a reversible non-selective MAOI), lithium, tramadol, or St. John’s Wort [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]. The concomitant use of fluoxetine with SNRIs, SSRIs, or tryptophan is not recommended [see Drug Interactions (7.4), (7.5)].

7.4 Triptans

There have been rare postmarketing reports of serotonin syndrome with use of an SSRI and a triptan. If concomitant treatment of fluoxetine with a triptan is clinically warranted, careful observation of the patient is advised, particularly during treatment initiation and dose increases [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2) and Drug Interactions (7.3)].

7.5 Tryptophan

Five patients receiving fluoxetine in combination with tryptophan experienced adverse reactions, including agitation, restlessness, and gastrointestinal distress. The concomitant use with tryptophan is not recommended [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2) and Drug Interactions (7.3)].

7.6 Drugs That Interfere With Hemostasis (e.g., NSAIDS, Aspirin, Warfarin)

Serotonin release by platelets plays an important role in hemostasis. Epidemiological studies of the case-control and cohort design that have demonstrated an association between use of psychotropic drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding have also shown that concurrent use of an NSAID or aspirin may potentiate this risk of bleeding. Altered anticoagulant effects, including increased bleeding, have been reported when SNRIs or SSRIs are coadministered with warfarin. Patients receiving warfarin therapy should be carefully monitored when fluoxetine is initiated or discontinued [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)].

7.7 Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

There are no clinical studies establishing the benefit of the combined use of ECT and fluoxetine. There have been rare reports of prolonged seizures in patients on fluoxetine receiving ECT treatment.

7.8 Potential for Other Drugs to Affect Fluoxetine

Drugs Tightly Bound to Plasma Proteins – Because fluoxetine is tightly bound to plasma proteins, adverse effects may result from displacement of protein-bound fluoxetine by other tightly-bound drugs [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.9 Potential for Fluoxetine to Affect Other Drugs

Pimozide – Concomitant use in patients taking pimozide is contraindicated. Clinical studies of pimozide with other antidepressants demonstrate an increase in drug interaction or QTc prolongation. While a specific study with pimozide and fluoxetine has not been conducted, the potential for drug interactions or QTc prolongation warrants restricting the concurrent use of pimozide and fluoxetine [see Contraindications (4)].

Thioridazine – Thioridazine should not be administered with fluoxetine or within a minimum of 5 weeks after fluoxetine has been discontinued [see Contraindications (4)].

In a study of 19 healthy male subjects, which included 6 slow and 13 rapid hydroxylators of debrisoquin, a single 25 mg oral dose of thioridazine produced a 2.4 fold higher Cmax and a 4.5 fold higher AUC for thioridazine in the slow hydroxylators compared with the rapid hydroxylators. The rate of debrisoquin hydroxylation is felt to depend on the level of CYP2D6 isozyme activity. Thus, this study suggests that drugs which inhibit CYP2D6, such as certain SSRIs, including fluoxetine, will produce elevated plasma levels of thioridazine.

Thioridazine administration produces a dose-related prolongation of the QTc interval, which is associated with serious ventricular arrhythmias, such as torsade de pointes-type arrhythmias, and sudden death. This risk is expected to increase with fluoxetine-induced inhibition of thioridazine metabolism.

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6 – Fluoxetine inhibits the activity of CYP2D6, and may make individuals with normal CYP2D6 metabolic activity resemble a poor metabolizer. Coadministration of fluoxetine with other drugs that are metabolized by CYP2D6, including certain antidepressants (e.g., TCAs), antipsychotics (e.g., phenothiazines and most atypicals), and antiarrhythmics (e.g., propafenone, flecainide, and others) should be approached with caution. Therapy with medications that are predominantly metabolized by the CYP2D6 system and that have a relatively narrow therapeutic index (see list below) should be initiated at the low end of the dose range if a patient is receiving fluoxetine concurrently or has taken it in the previous 5 weeks. Thus, his/her dosing requirements resemble those of poor metabolizers. If fluoxetine is added to the treatment regimen of a patient already receiving a drug metabolized by CYP2D6, the need for decreased dose of the original medication should be considered. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index represent the greatest concern (e.g., flecainide, propafenone, vinblastine, and TCAs). Due to the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death potentially associated with elevated plasma levels of thioridazine, thioridazine should not be administered with fluoxetine or within a minimum of 5 weeks after fluoxetine has been discontinued [see Contraindications (4)].

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) — In 2 studies, previously stable plasma levels of imipramine and desipramine have increased greater than 2 to 10 fold when fluoxetine has been administered in combination. This influence may persist for 3 weeks or longer after fluoxetine is discontinued. Thus, the dose of TCAs may need to be reduced and plasma TCA concentrations may need to be monitored temporarily when fluoxetine is coadministered or has been recently discontinued [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Benzodiazapines — The half-life of concurrently administered diazepam may be prolonged in some patients [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Coadministration of alprazolam and fluoxetine has resulted in increased alprazolam plasma concentrations and in further psychomotor performance decrement due to increased alprazolam levels.

Antipsychotics — Some clinical data suggests a possible pharmacodynamic and/or pharmacokinetic interaction between SSRIs and antipsychotics. Elevation of blood levels of haloperidol and clozapine has been observed in patients receiving concomitant fluoxetine [see Contraindications (4)].

Anticonvulsants — Patients on stable doses of phenytoin and carbamazepine have developed elevated plasma anticonvulsant concentrations and clinical anticonvulsant toxicity following initiation of concomitant fluoxetine treatment.

Lithium — There have been reports of both increased and decreased lithium levels when lithium was used concomitantly with fluoxetine. Cases of lithium toxicity and increased serotonergic effects have been reported. Lithium levels should be monitored when these drugs are administered concomitantly.

Drugs Tightly Bound to Plasma Proteins — Because fluoxetine is tightly bound to plasma proteins, the administration of fluoxetine to a patient taking another drug that is tightly bound to protein (e.g., Coumadin, digitoxin) may cause a shift in plasma concentrations potentially resulting in an adverse effect [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Drugs Metabolized by CYP3A4 — In an in vivo interaction study involving coadministration of fluoxetine with single doses of terfenadine (a CYP3A4 substrate), no increase in plasma terfenadine concentrations occurred with concomitant fluoxetine.

Additionally, in vitro studies have shown ketoconazole, a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 activity, to be at least 100 times more potent than fluoxetine or norfluoxetine as an inhibitor of the metabolism of several substrates for this enzyme, including astemizole, cisapride, and midazolam. These data indicate that fluoxetine’s extent of inhibition of CYP3A4 activity is not likely to be of clinical significance.

Olanzapine — Fluoxetine (60 mg single dose or 60 mg daily dose for 8 days) causes a small (mean 16%) increase in the maximum concentration of olanzapine and a small (mean 16%) decrease in olanzapine clearance. The magnitude of the impact of this factor is small in comparison to the overall variability between individuals, and therefore dose modification is not routinely recommended.

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Drug Interactions section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

When using fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination, also refer to the Use in Specific Populations section of the package insert for olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules.

8.1 Pregnancy

Teratogenic Effects

Pregnancy Category C - Fluoxetine should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defects, loss, or other adverse outcome regardless of drug exposure.

Treatment of Pregnant Women During the First Trimester — There are no adequate and well-controlled clinical studies on the use of fluoxetine in pregnant women. Results of a number of published epidemiological studies assessing the risk of fluoxetine exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy have demonstrated inconsistent results. More than 10 cohort studies and case-control studies failed to demonstrate an increased risk for congenital malformations overall. However, one prospective cohort study conducted by the European Network of Teratology Information Services reported an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations in infants born to women (N = 253) exposed to fluoxetine during the first trimester of pregnancy compared to infants of women (N = 1,359) who were not exposed to fluoxetine. There was no specific pattern of cardiovascular malformations. Overall, however, a causal relationship has not been established.

Treatment of Pregnant Women During the Third Trimester — Neonates exposed to fluoxetine, SNRIs, or SSRIs, late in the third trimester have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding. Such complications can arise immediately upon delivery. Reported clinical findings have included respiratory distress, cyanosis, apnea, seizures, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotonia, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, tremor, jitteriness, irritability, and constant crying. These features are consistent with either a direct toxic effect of SNRIs and SSRIs or, possibly, a drug discontinuation syndrome. It should be noted that, in some cases, the clinical picture is consistent with serotonin syndrome.

Infants exposed to SSRIs in late pregnancy may have an increased risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). PPHN occurs in 1 to 2 per 1000 live births in the general population and is associated with substantial neonatal morbidity and mortality. In a retrospective case-control study of 377 women whose infants were born with PPHN and 836 women whose infants were born healthy, the risk for developing PPHN was approximately six-fold higher for infants exposed to SSRIs after the 20th week of gestation compared to infants who had not been exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy. There is currently no corroborative evidence regarding the risk for PPHN following exposure to SSRIs in pregnancy; this is the first study that has investigated the potential risk. The study did not include enough cases with exposure to individual SSRIs to determine if all SSRIs posed similar levels of PPHN risk.

Clinical Considerations— When treating pregnant women with fluoxetine, the physician should carefully consider both the potential risks and potential benefits of treatment, taking into account the risk of untreated depression during pregnancy. Physicians should note that in a prospective longitudinal study of 201 women with a history of major depression who were euthymic at the beginning of pregnancy, women who discontinued antidepressant medication during pregnancy were more likely to experience a relapse of major depression than women who continued antidepressant medication.

The physician may consider tapering fluoxetine in the third trimester [see Dosage and Administration (2.7)].

Animal Data — In embryo-fetal development studies in rats and rabbits, there was no evidence of teratogenicity following administration of fluoxetine at doses up to 12.5 and 15 mg/kg/day, respectively (1.5 and 3.6 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 80 mg on a mg/m2 basis) throughout organogenesis. However, in rat reproduction studies, an increase in stillborn pups, a decrease in pup weight, and an increase in pup deaths during the first 7 days postpartum occurred following maternal exposure to 12 mg/kg/day (1.5 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) during gestation or 7.5 mg/kg/day (0.9 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) during gestation and lactation. There was no evidence of developmental neurotoxicity in the surviving offspring of rats treated with 12 mg/kg/day during gestation. The no-effect dose for rat pup mortality was 5 mg/kg/day (0.6 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis).

8.2 Labor and Delivery

The effect of fluoxetine on labor and delivery in humans is unknown. However, because fluoxetine crosses the placenta and because of the possibility that fluoxetine may have adverse effects on the newborn, fluoxetine should be used during labor and delivery only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

8.3 Nursing Mothers

Because fluoxetine is excreted in human milk, nursing while on fluoxetine is not recommended. In one breast-milk sample, the concentration of fluoxetine plus norfluoxetine was 70.4 ng/mL. The concentration in the mother’s plasma was 295.0 ng/mL. No adverse effects on the infant were reported. In another case, an infant nursed by a mother on fluoxetine developed crying, sleep disturbance, vomiting, and watery stools. The infant’s plasma drug levels were 340 ng/mL of fluoxetine and 208 ng/mL of norfluoxetine on the second day of feeding.

8.4 Pediatric Use

The efficacy of fluoxetine for the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder was demonstrated in two 8 to 9 week placebo-controlled clinical trials with 315 pediatric outpatients ages 8 to ≤ 18 [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

The efficacy of fluoxetine for the treatment of OCD was demonstrated in one 13 week placebo-controlled clinical trial with 103 pediatric outpatients ages 7 to < 18 [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

The safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients < 8 years of age in Major Depressive Disorder and < 7 years of age in OCD have not been established.

Fluoxetine pharmacokinetics were evaluated in 21 pediatric patients (ages 6 to ≤ 18) with Major Depressive Disorder or OCD [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

The acute adverse reaction profiles observed in the 3 studies (N = 418 randomized; 228 fluoxetine-treated, 190 placebo-treated) were generally similar to that observed in adult studies with fluoxetine. The longer-term adverse reaction profile observed in the 19 week Major Depressive Disorder study (N = 219 randomized; 109 fluoxetine-treated, 110 placebo-treated) was also similar to that observed in adult trials with fluoxetine [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

Manic reaction, including mania and hypomania, was reported in 6 (1 mania, 5 hypomania) out of 228 (2.6%) fluoxetine-treated patients and in 0 out of 190 (0%) placebo-treated patients. Mania/hypomania led to the discontinuation of 4 (1.8%) fluoxetine-treated patients from the acute phases of the 3 studies combined. Consequently, regular monitoring for the occurrence of mania/hypomania is recommended.

As with other SSRIs, decreased weight gain has been observed in association with the use of fluoxetine in children and adolescent patients. After 19 weeks of treatment in a clinical trial, pediatric subjects treated with fluoxetine gained an average of 1.1 cm less in height and 1.1 kg less in weight than subjects treated with placebo. In addition, fluoxetine treatment was associated with a decrease in alkaline phosphatase levels. The safety of fluoxetine treatment for pediatric patients has not been systematically assessed for chronic treatment longer than several months in duration. In particular, there are no studies that directly evaluate the longer-term effects of fluoxetine on the growth, development and maturation of children and adolescent patients. Therefore, height and weight should be monitored periodically in pediatric patients receiving fluoxetine [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

Fluoxetine is approved for use in pediatric patients with MDD and OCD [see Box Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]. Anyone considering the use of fluoxetine in a child or adolescent must balance the potential risks with the clinical need.

Significant toxicity, including myotoxicity, long-term neurobehavioral and reproductive toxicity, and impaired bone development, has been observed following exposure of juvenile animals to fluoxetine. Some of these effects occurred at clinically relevant exposures.

In a study in which fluoxetine (3, 10, or 30 mg/kg) was orally administered to young rats from weaning (Postnatal Day 21) through adulthood (Day 90), male and female sexual development was delayed at all doses, and growth (body weight gain, femur length) was decreased during the dosing period in animals receiving the highest dose. At the end of the treatment period, serum levels of creatine kinase (marker of muscle damage) were increased at the intermediate and high doses, and abnormal muscle and reproductive organ histopathology (skeletal muscle degeneration and necrosis, testicular degeneration and necrosis, epididymal vacuolation and hypospermia) was observed at the high dose. When animals were evaluated after a recovery period (up to 11 weeks after cessation of dosing), neurobehavioral abnormalities (decreased reactivity at all doses and learning deficit at the high dose) and reproductive functional impairment (decreased mating at all doses and impaired fertility at the high dose) were seen; in addition, testicular and epididymal microscopic lesions and decreased sperm concentrations were found in the high dose group, indicating that the reproductive organ effects seen at the end of treatment were irreversible. The reversibility of fluoxetine-induced muscle damage was not assessed. Adverse effects similar to those observed in rats treated with fluoxetine during the juvenile period have not been reported after administration of fluoxetine to adult animals. Plasma exposures (AUC) to fluoxetine in juvenile rats receiving the low, intermediate, and high dose in this study were approximately 0.1 to 0.2, 1 to 2, and 5 to 10 times, respectively, the average exposure in pediatric patients receiving the maximum recommended dose (MRD) of 20 mg/day. Rat exposures to the major metabolite, norfluoxetine, were approximately 0.3 to 0.8, 1 to 8, and 3 to 20 times, respectively, pediatric exposure at the MRD.

A specific effect of fluoxetine on bone development has been reported in mice treated with fluoxetine during the juvenile period. When mice were treated with fluoxetine (5 or 20 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) for 4 weeks starting at 4 weeks of age, bone formation was reduced resulting in decreased bone mineral content and density. These doses did not affect overall growth (body weight gain or femoral length). The doses administered to juvenile mice in this study are approximately 0.5 and 2 times the MRD for pediatric patients on a body surface area (mg/m2) basis.

In another mouse study, administration of fluoxetine (10 mg/kg intraperitoneal) during early postnatal development (Postnatal Days 4 to 21) produced abnormal emotional behaviors (decreased exploratory behavior in elevated plus-maze, increase shock avoidance latency) in adulthood (12 weeks of age). The dose used in this study is approximately equal to the pediatric MRD on a mg/m2 basis. Because of the early dosing period in this study, the significance of these findings to the approved pediatric use in humans is uncertain.

Safety and effectiveness of fluoxetine and olanzapine in combination in patients less than 18 years of age have not been established.

8.5 Geriatric Use

U.S. fluoxetine clinical trials included 687 patients ≥ 65 years of age and 93 patients ≥ 75 years of age. The efficacy in geriatric patients has been established [see Clinical Studies (14.1)]. For pharmacokinetic information in geriatric patients, [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.4)]. No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between these subjects and younger subjects, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out. SNRIs and SSRIs, including fluoxetine, have been associated with cases of clinically significant hyponatremia in elderly patients, who may be at greater risk for this adverse reaction [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

Clinical studies of olanzapine and fluoxetine in combination did not include sufficient numbers of patients ≥ 65 years of age to determine whether they respond differently from younger patients.

8.6 Hepatic Impairment

In subjects with cirrhosis of the liver, the clearances of fluoxetine and its active metabolite, norfluoxetine, were decreased, thus increasing the elimination half-lives of these substances. A lower or less frequent dose of fluoxetine should be used in patients with cirrhosis. Caution is advised when using fluoxetine in patients with diseases or conditions that could affect its metabolism [see Dosage and Administration (2.7) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.4)].

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.3 Dependence

Fluoxetine has not been systematically studied, in animals or humans, for its potential for abuse, tolerance, or physical dependence. While the premarketing clinical experience with fluoxetine did not reveal any tendency for a withdrawal syndrome or any drug seeking behavior, these observations were not systematic and it is not possible to predict on the basis of this limited experience the extent to which a CNS active drug will be misused, diverted, and/or abused once marketed. Consequently, physicians should carefully evaluate patients for history of drug abuse and follow such patients closely, observing them for signs of misuse or abuse of fluoxetine (e.g., development of tolerance, incrementation of dose, drug-seeking behavior).

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

Worldwide exposure to fluoxetine hydrochloride is estimated to be over 38 million patients (circa 1999). Of the 1578 cases of overdose involving fluoxetine hydrochloride, alone or with other drugs, reported from this population, there were 195 deaths.

Among 633 adult patients who overdosed on fluoxetine hydrochloride alone, 34 resulted in a fatal outcome, 378 completely recovered, and 15 patients experienced sequelae after overdosage, including abnormal accommodation, abnormal gait, confusion, unresponsiveness, nervousness, pulmonary dysfunction, vertigo, tremor, elevated blood pressure, impotence, movement disorder, and hypomania. The remaining 206 patients had an unknown outcome. The most common signs and symptoms associated with non-fatal overdosage were seizures, somnolence, nausea, tachycardia, and vomiting. The largest known ingestion of fluoxetine hydrochloride in adult patients was 8 grams in a patient who took fluoxetine alone and who subsequently recovered. However, in an adult patient who took fluoxetine alone, an ingestion as low as 520 mg has been associated with lethal outcome, but causality has not been established.

Among pediatric patients (ages 3 months to 17 years), there were 156 cases of overdose involving fluoxetine alone or in combination with other drugs. Six patients died, 127 patients completely recovered, 1 patient experienced renal failure, and 22 patients had an unknown outcome. One of the six fatalities was a 9-year-old boy who had a history of OCD, Tourette’s syndrome with tics, attention deficit disorder, and fetal alcohol syndrome. He had been receiving 100 mg of fluoxetine daily for 6 months in addition to clonidine, methylphenidate, and promethazine. Mixed-drug ingestion or other methods of suicide complicated all 6 overdoses in children that resulted in fatalities. The largest ingestion in pediatric patients was 3 grams which was nonlethal.

Other important adverse reactions reported with fluoxetine overdose (single or multiple drugs) include coma, delirium, ECG abnormalities (such as QT interval prolongation and ventricular tachycardia, including torsade de pointes-type arrhythmias), hypotension, mania, neuroleptic malignant syndrome-like reactions, pyrexia, stupor, and syncope.

10.2 Animal Experience

Studies in animals do not provide precise or necessarily valid information about the treatment of human overdose. However, animal experiments can provide useful insights into possible treatment strategies.

The oral median lethal dose in rats and mice was found to be 452 and 248 mg/kg, respectively. Acute high oral doses produced hyperirritability and convulsions in several animal species.