WARNING

Only physicians experienced in cancer chemotherapy should use Cytarabine Injection.

For induction therapy patients should be treated in a facility with laboratory and supportive resources sufficient to monitor drug tolerance and protect and maintain a patient compromised by drug toxicity. The main toxic effect of cytarabine injection is bone marrow suppression with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia. Less serious toxicity includes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain, oral ulceration, and hepatic dysfunction.

The physician must judge possible benefit to the patient against known toxic effects of this drug in considering the advisability of therapy with Cytarabine Injection. Before making this judgment or beginning treatment, the physician should be familiar with the following text.

DESCRIPTION:

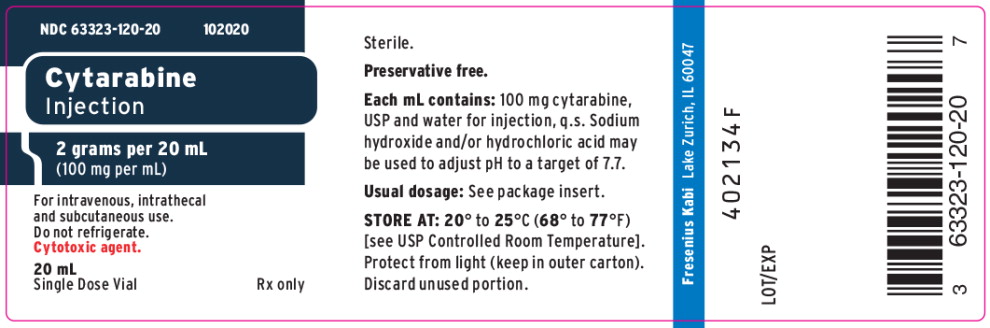

Cytarabine Injection, an antineoplastic, is a sterile solution of cytarabine for intravenous, intrathecal or subcutaneous administration. Each mL contains 100 mg cytarabine USP, in 2 g/20 mL (100 mg/mL) single dose vial and the following inactive ingredients: water for injection q.s. When necessary the pH is adjusted with hydrochloric acid and/or sodium hydroxide to a pH of 7.7.

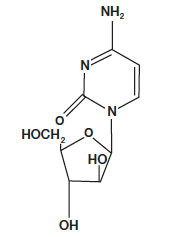

Cytarabine is chemically 1-β-D-Arabinofuranosylcytosine. The structural formula is:

C 9H 13N 3O 5 M.W. 243.22

Cytarabine is an odorless, white to off-white crystalline powder which is freely soluble in water and slightly soluble in alcohol and in chloroform.

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY:

Cell Culture Studies

Cytarabine is cytotoxic to a wide variety of proliferating mammalian cells in culture. It exhibits cell phase specificity, primarily killing cells undergoing DNA synthesis (S-phase) and under certain conditions blocking the progression of cells from the G1 phase to the S-phase. Although the mechanism of action is not completely understood, it appears that cytarabine acts through the inhibition of DNA polymerase. A limited, but significant, incorporation of cytarabine into both DNA and RNA has also been reported. Extensive chromosomal damage, including chromatoid breaks, have been produced by cytarabine and malignant transformation of rodent cells in culture has been reported. Deoxycytidine prevents or delays (but does not reverse) the cytotoxic activity.

Cellular Resistance and Sensitivity

Cytarabine is metabolized by deoxycytidine kinase and other nucleotide kinases to the nucleotide triphosphate, an effective inhibitor of DNA polymerase; it is inactivated by a pyrimidine nucleoside deaminase, which converts it to the non-toxic uracil derivative. It appears that the balance of kinase and deaminase levels may be an important factor in determining sensitivity or resistance of the cell to cytarabine.

Human Pharmacology

Cytarabine is rapidly metabolized and is not effective orally; less than 20 percent of the orally administered dose is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.

Following rapid intravenous injection of cytarabine labeled with tritium, the disappearance from plasma is biphasic. There is an initial distributive phase with a half-life of about 10 minutes, followed by a second elimination phase with a half-life of about 1 to 3 hours. After the distributive phase, more than 80 percent of plasma radioactivity can be accounted for by the inactive metabolite 1-β-D-arabinofuranosyluracil (ara-U). Within 24 hours about 80 percent of the administered radioactivity can be recovered in the urine, approximately 90 percent of which is excreted as ara-U.

Relatively constant plasma levels can be achieved by continuous intravenous infusion.

After subcutaneous or intramuscular administration of cytarabine labeled with tritium, peak-plasma levels of radioactivity are achieved about 20 to 60 minutes after injection and are considerably lower than those after intravenous administration.

Cerebrospinal fluid levels of cytarabine are low in comparison to plasma levels after single intravenous injection. However, in one patient in whom cerebrospinal fluid levels are examined after 2 hours of constant intravenous infusion, levels approached 40 percent of the steady state plasma level. With intrathecal administration, levels of cytarabine in the cerebrospinal fluid declined with a first order half-life of about 2 hours. Because cerebrospinal fluid levels of deaminase are low, little conversion to ara-U was observed.

Immunosuppressive Action

Cytarabine Injection is capable of obliterating immune responses in man during administration with little or no accompanying toxicity. Suppression of antibody responses to E-coli-VI antigen and tetanus toxoid have been demonstrated. This suppression was obtained during both primary and secondary antibody responses.

Cytarabine also suppressed the development of cell-mediated immune responses such as delayed hypersensitivity skin reaction to dinitrochlorobenzene. However, it had no effect on already established delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Following 5-day courses of intensive therapy with cytarabine the immune response was suppressed, as indicated by the following parameters: macrophage ingress into skin windows; circulating antibody response following primary antigenic stimulation; lymphocyte blastogenesis with phytohemagglutinin. A few days after termination of therapy there was a rapid return to normal.

INDICATIONS AND USAGE:

Cytarabine Injection in combination with other approved anti-cancer drugs is indicated for remission induction in acute non-lymphocytic leukemia of adults and pediatric patients. It has also been found useful in the treatment of acute non-lymphocytic leukemia and the blast phase of chronic myelocytic leukemia. Intrathecal administration of Cytarabine Injection (preservative free preparations only) is indicated in the prophylaxis and treatment of meningeal leukemia.

CONTRAINDICATIONS:

Cytarabine Injection is contraindicated in those patients who are hypersensitive to the drug.

WARNINGS:

(See boxed WARNING)

Cytarabine is a potent bone marrow suppressant. Therapy should be started cautiously in patients with pre-existing drug-induced bone marrow suppression. Patients receiving this drug must be under close medical supervision and, during induction therapy, should have leucocyte and platelet counts performed daily. Bone marrow examinations should be performed frequently after blasts have disappeared from the peripheral blood. Facilities should be available for management of complications, possibly fatal, of bone marrow suppression (infection resulting from granulocytopenia and other impaired body defenses, and hemorrhage secondary to thrombocytopenia). One case of anaphylaxis that resulted in acute cardiopulmonary arrest and required resuscitation has been reported. This occurred immediately after the intravenous administration of cytarabine.

Severe and at times fatal CNS, GI and pulmonary toxicity (different from that seen with conventional therapy regimens of cytarabine) has been reported following some experimental dose schedules for cytarabine. These reactions include reversible corneal toxicity, and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, which may be prevented or diminished by prophylaxis with a local corticosteroid eye drop; cerebral and cerebellar dysfunction, including personality changes, somnolence and coma, usually reversible; severe gastrointestinal ulceration, including pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis leading to peritonitis; sepsis and liver abscess; pulmonary edema, liver damage with increased hyperbilirubinemia; bowel necrosis; and necrotizing colitis. Rarely, severe skin rash, leading to desquamation has been reported. Complete alopecia is more commonly seen with experimental high dose therapy than with standard treatment programs using cytarabine injection. If experimental high dose therapy is used, do not use a preparation containing benzyl alcohol.

Cases of cardiomyopathy with subsequent death have been reported following experimental high dose therapy with cytarabine in combination with cyclophosphamide when used for bone marrow transplant preparation.

A syndrome of sudden respiratory distress, rapidly progressing to pulmonary edema and radiographically pronounced cardiomegaly has been reported following experimental high dose therapy with cytarabine used for the treatment of relapsed leukemia from one institution in 16/72 patients. The outcome of this syndrome can be fatal.

Two patients with childhood acute myelogenous leukemia who received intrathecal and intravenous cytarabine at conventional doses (in addition to a number of other concomitantly administered drugs) developed delayed progressive ascending paralysis resulting in death in one of the two patients.

Use in Pregnancy (Category D)

Cytarabine can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Cytarabine causes abnormal cerebellar development in the neonatal hamster and is teratogenic to the rat fetus. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Women of childbearing potential should be advised to avoid becoming pregnant.

A review of the literature has shown 32 reported cases where cytarabine was given during pregnancy, either alone or in combination with other cytotoxic agents:

Eighteen normal infants were delivered. Four of these had first trimester exposure. Five infants were premature or of low birth weight. Twelve of the 18 normal infants were followed up at ages ranging from six weeks to seven years, and showed no abnormalities. One apparently normal infant died at 90 days of gastroenteritis.

Two cases of congenital abnormalities have been reported, one with upper and lower distal limb defects, and the other with extremity and ear deformities. Both of these cases had first trimester exposure.

There were seven infants with various problems in the neonatal period, including pancytopenia, transient depression of WBC, hematocrit or platelets; electrolyte abnormalities; transient eosinophilia; and one case of increased IgM levels and hyperpyrexia possibly due to sepsis. Six of the seven infants were also premature. The child with pancytopenia died at 21 days of sepsis.

Therapeutic abortions were done in five cases. Four fetuses were grossly normal, but one had an enlarged spleen and another showed Trisomy C chromosome abnormality in the chorionic tissue.

Because of the potential for abnormalities with cytotoxic therapy, particularly during the first trimester, a patient who is or who may become pregnant while on cytarabine should be apprised of the potential risk to the fetus and the advisability of pregnancy continuation. There is a definite, but considerably reduced risk if therapy is initiated during the second or third trimester. Although normal infants have been delivered to patients treated in all three trimesters of pregnancy, follow-up of such infants would be advisable.

PRECAUTIONS:

General Precautions

Patients receiving cytarabine must be monitored closely. Frequent platelet and leucocyte counts and bone marrow examinations are mandatory. Consider suspending or modifying therapy when drug-induced marrow depression has resulted in a platelet count under 50,000 or a polymorphonuclear granulocyte count under 1,000/mm3. Counts of formed elements in the peripheral blood may continue to fall after the drug is stopped and reach lowest values after drug-free intervals of 12 to 24 days. When indicated, restart therapy when definite signs of marrow recovery appear (on successive bone marrow studies). Patients whose drug is withheld until “normal” peripheral blood values are attained may escape from control.

When large intravenous doses are given too quickly, patients are frequently nauseated and may vomit for several hours post-injection. This problem tends to be less severe when the drug is infused.

The human liver apparently detoxifies a substantial fraction of an administered dose. In particular, patients with renal or hepatic function impairment may have a higher likelihood of CNS toxicity after high-dose cytarabine treatment. Use the drug with caution and possibly at reduced dose in patients whose liver or kidney function is poor.

Periodic checks of bone marrow, liver and kidney functions should be performed in patients receiving cytarabine.

Like other cytotoxic drugs, cytarabine may induce hyperuricemia secondary to rapid lysis of neoplastic cells. The clinician should monitor the patient's blood uric acid level and be prepared to use such supportive and pharmacologic measures as might be necessary to control this problem.

Acute pancreatitis has been reported to occur in a patient receiving cytarabine by continuous infusion and in patients being treated with cytarabine who have had prior treatment with L-asparaginase.

Drug Interactions

Reversible decreases in steady-state plasma digoxin concentrations and renal glycoside excretion were observed in patients receiving beta-acetyldigoxin and chemotherapy regimens containing cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone with or without cytarabine or procarbazine.

Steady-state plasma digitoxin concentrations did not appear to change. Therefore, monitoring of plasma digoxin levels may be indicated in patients receiving similar combination chemotherapy regimens. The utilization of digitoxin for such patients may be considered as an alternative.

An in vitro interaction study between gentamicin and cytarabine showed a cytarabine related antagonism for the susceptibility of K. pneumoniae strains. This study suggests that in patients on cytarabine being treated with gentamicin for a K. pneumoniae infection, the lack of a prompt therapeutic response may indicate the need for re-evaluation of antibacterial therapy.

Clinical evidence in one patient showed possible inhibition of fluorocytosine efficacy during therapy with cytarabine. This may be due to potential competitive inhibition of its uptake.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Extensive chromosomal damage, including chromatoid breaks have been produced by cytarabine and malignant transformation of rodent cells in culture has been reported.

Nursing Mothers

It is not known whether this drug is excreted in human milk. Because many drugs are excreted in human milk and because of the potential for serious adverse reactions in nursing infants from cytarabine, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother.

ADVERSE REACTIONS:

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC at 1-800-551-7176 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

Expected Reactions

Because cytarabine is a bone marrow suppressant, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, megaloblastosis and reduced reticulocytes can be expected as a result of administration with cytarabine. The severity of these reactions are dose and schedule dependent. Cellular changes in the morphology of bone marrow and peripheral smears can be expected.

Following 5-day constant infusions or acute injections of 50 mg/m2 to 600 mg/m2, white cell depression follows a biphasic course. Regardless of initial count, dosage level, or schedule, there is an initial fall starting the first 24 hours with a nadir at days 7 to 9. This is followed by a brief rise which peaks around the twelfth day. A second and deeper fall reaches nadir at days 15 to 24. Then there is a rapid rise to above baseline in the next 10 days. Platelet depression is noticeable at 5 days with a peak depression occurring between days 12 to 15. Thereupon, a rapid rise to above baseline occurs in the next 10 days.

Infectious Complications

Injection

Viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic, or saprophytic infections, in any location in the body may be associated with the use of cytarabine alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive agents following immunosuppressant doses that affect cellular or humoral immunity. These infections may be mild, but can be severe and at times fatal.

The Cytarabine (Ara-C) Syndrome

A cytarabine syndrome has been described by Castleberry. It is characterized by fever, myalgia, bone pain, occasionally chest pain, maculopapular rash, conjunctivitis and malaise. It usually occurs 6 to 12 hours following drug administration. Corticosteroids have been shown to be beneficial in treating or preventing this syndrome. If the symptoms of the syndrome are deemed treatable, corticosteroids should be contemplated as well as continuation of therapy with cytarabine.

| Anorexia | Oral and anal inflammation or ulceration | Rash |

| Nausea | Thrombophlebitis | |

| Vomiting | Hepatic dysfunction | Bleeding (all sites) |

| Diarrhea | Fever | |

| Nausea and vomiting are most frequent following rapid intravenous injection. | ||

| Sepsis | Sore throat | Conjunctivitis (may occur with rash) |

| Pneumonia | Esophageal ulceration | Dizziness |

| Cellulitis at injection site | Esophagitis | Alopecia |

| Skin ulceration | Chest pain | Anaphylaxis (see WARNING) |

| Urinary retention | Pericarditis | Allergic edema |

| Renal dysfunction | Bowel necrosis | Pruritus |

| Neuritis | Abdominal pain | Shortness of breath |

| Neural toxicity | Pancreatitis | Urticaria |

| Freckling | Headache | |

| Jaundice | Sinus bradycardia |

Experimental Doses

Severe and at times fatal CNS, GI and pulmonary toxicity (different from that seen with conventional therapy regimens of cytarabine) has been reported following some experimental dose schedules of cytarabine. These reactions include reversible corneal toxicity and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, which may be prevented or diminished by prophylaxis with a local corticosteroid eye drop; cerebral and cerebellar dysfunction, including personality changes, somnolence and coma, usually reversible; severe gastrointestinal ulceration, including pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis leading to peritonitis; sepsis and liver abscess; pulmonary edema, liver damage with increased hyperbilirubinemia; bowel necrosis; and necrotizing colitis. Rarely, severe skin rash, leading to desquamation has been reported. Complete alopecia is more commonly seen with experimental high dose therapy than with standard treatment programs using cytarabine. If experimental high dose therapy is used, do not use a preparation containing benzyl alcohol.

Cases of cardiomyopathy with subsequent death have been reported following experimental high dose therapy with cytarabine in combination with cyclophosphamide when used for bone marrow transplant preparation.

This cardiac toxicity may be schedule dependent.

A syndrome of sudden respiratory distress, rapidly progressing to pulmonary edema and radiographically pronounced cardiomegaly has been reported following experimental high dose therapy with cytarabine used for the treatment of relapsed leukemia from one institution in 16/72 patients. The outcome of this syndrome can be fatal.

Two patients with adult acute non-lymphocytic leukemia developed peripheral motor and sensory neuropathies after consolidation with high-dose cytarabine, daunorubicin, and asparaginase. Patients treated with high-dose cytarabine should be observed for neuropathy since dose schedule alterations may be needed to avoid irreversible neurologic disorders.

Ten patients treated with experimental intermediate doses of cytarabine (1 g/m2) with and without other chemotherapeutic agents (meta-AMSA, daunorubicin, etoposide) at various dose regimes developed a diffuse interstitial pneumonitis without clear cause that may have been related to the cytarabine.

Two cases of pancreatitis have been reported following experimental doses of cytarabine and numerous other drugs. Cytarabine could have been the causative agent.

OVERDOSAGE:

There is no antidote for overdosage of cytarabine. Doses of 4.5 g/m2 by intravenous infusion over 1 hour every 12 hours for 12 doses have caused an unacceptable increase in irreversible CNS toxicity and death.

Single doses as high as 3 g/m2 have been administered by rapid intravenous infusion without apparent toxicity.

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION:

Cytarabine Injection is not active orally. The schedule and method of administration varies with the program of therapy to be used. Cytarabine Injection may be given by intravenous infusion or injection, subcutaneously, or intrathecally (preservative free preparation only).

Thrombophlebitis has occurred at the site of drug injection or infusion in some patients, and rarely patients have noted pain and inflammation at subcutaneous injection sites. In most instances, however, the drug has been well tolerated.

Patients can tolerate higher total doses when they receive the drug by rapid intravenous injection as compared with slow infusion. This phenomenon is related to the drug's rapid inactivation and brief exposure of susceptible normal and neoplastic cells to significant levels after rapid injection. Normal and neoplastic cells seem to respond in somewhat parallel fashion to these different modes of administration and no clear-cut clinical advantage has been demonstrated for either.

In the induction therapy of acute non-lymphocytic leukemia, the usual cytarabine dose in combination with other anticancer drugs is 100 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion (Days 1 to 7) or 100 mg/m2 IV every 12 hours (Days 1 to 7).

The literature should be consulted for the current recommendations for use in acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Intrathecal Use in Meningeal Leukemia

Cytarabine Injection has been used intrathecally in acute leukemia in doses ranging from 5 mg/m2 to 75 mg/m2 of body surface area. The frequency of administration varied from once a day for 4 days to once every 4 days. The most frequently used dose was 30 mg/m2 every 4 days until cerebrospinal fluid findings were normal, followed by one additional treatment. The dosage schedule is usually governed by the type and severity of central nervous system manifestations and the response to previous therapy.

Cytarabine Injection given intrathecally may cause systemic toxicity and careful monitoring of the hematopoietic system is indicated. Modification of other anti-leukemia therapy may be necessary. Major toxicity is rare. The most frequently reported reactions after intrathecal administration were nausea, vomiting, and fever; these reactions are mild and self-limiting. Paraplegia has been reported. Necrotizing leukoencephalopathy occurred in 5 children; these patients had also been treated with intrathecal methotrexate and hydrocortisone, as well as by central nervous system radiation. Isolated neurotoxicity has been reported. Blindness occurred in two patients in remission whose treatment had consisted of combination systemic chemotherapy, prophylactic central nervous system radiation and intrathecal Cytarabine Injection.

When Cytarabine Injection is administered both intrathecally and intravenously within a few days, there is an increased risk of spinal cord toxicity, however, in serious life-threatening disease, concurrent use of intravenous and intrathecal Cytarabine Injection is left to the discretion of the treating physician.

Focal leukemic involvement of the central nervous system may not respond to intrathecal Cytarabine Injection and may better be treated with radiotherapy.

Chemical Stability of Infusion Solutions

Chemical stability studies were performed by HPLC on Cytarabine Injection in infusion solutions. These studies showed that when Cytarabine Injection was added to Water for Injection, 5% Dextrose in Water or Sodium Chloride Injection, 94 to 96 percent of the cytarabine was present after 192 hours storage at room temperature.

Parenteral drugs should be inspected visually for particulate matter and discoloration, prior to administration, whenever solution and container permit.

If a precipitate has formed as a result of exposure to low temperatures, redissolve by warming up to 55°C for no longer than 30 minutes, under dry heat conditions, and shake until the precipitate has dissolved.

HANDLING AND DISPOSAL:

Procedures for proper handling and disposal of anti-cancer drugs should be considered. Several guidelines on this subject have been published.1-7 There is no general agreement that all of the procedures recommended in the guidelines are necessary or appropriate.

HOW SUPPLIED:

| Product

No. | NDC

No. | |

| 102020 | 63323-120-20 | Cytarabine Injection, 2 g per 20 mL (100 mg per mL) sterile solution in a single dose flip cap vial, packaged individually. |

The container closure is not made with natural rubber latex.

STORAGE CONDITIONS:

Protect from light (keep in outer carton).

Store at 20° to 25°C (68° to 77°F) [see USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Do not refrigerate.

REFERENCES:

- Recommendations for the Safe Handling of Parenteral Antineoplastic Drugs, NIH Publication No. 83-2621. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402.

- AMA Council Report, Guidelines for Handling Parenteral Antineoplastics, JAMA, 1985; 2.53 (11): 1590-1592.

- National Study Commission on Cytotoxic Exposure-Recommendations for Handling Cytotoxic Agents. Available from Louis P. Jeffrey, ScD., Chairman, National Study Commission on Cytotoxic Exposure, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Allied Health Sciences, 179 Longwood Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115.

- Clinical Oncological Society of Australia, Guidelines and Recommendations for Safe Handling of Antineoplastic Agents. Med J Australia, 1983; 1:426-428.

- Jones RB, et al: Safe Handling of Chemotherapeutic Agents: A Report from the Mount Sinai Medical Center. CA-A Cancer Journal of Clinicians, 1983; (Sept/Oct) 258-263.

- American Society of Hospital Pharmacists Technical Assistance Bulletin on Handling Cytotoxic and Hazardous Drugs. Am J. Hosp. Pharm, 1990; 47:1033-1049.

- Controlling Occupational Exposure to Hazardous Drugs. (OSHA Work Practice Guidelines), Am J. Health-Syst Pharm, 1996; 53:1669-1685.

Lake Zurich, IL 60047

www.fresenius-kabi.com/us

45986E

Revised: May 2021