FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Cisatracurium besylate injection is indicated:

- •

- as an adjunct to general anesthesia to facilitate tracheal intubation in adults and in pediatric patients 1 month to 12 years of age

- •

- to provide skeletal muscle relaxation in adults during surgical procedures or during mechanical ventilation in the ICU

- •

- to provide skeletal muscle relaxation during surgical procedures via infusion in pediatric patients 2 years and older.

Limitations of Use

Cisatracurium besylate injection is not recommended for rapid sequence endotracheal intubation due to the time required for its onset of action.

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Important Dosage and Administration Instructions

Risk of Medication Errors

Accidental administration of neuromuscular blocking agents may be fatal. Store cisatracurium besylate injection with the cap and ferrule intact and in a manner that minimizes the possibility of selecting the wrong product [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)].

Important Administration Instructions

- •

- Cisatracurium besylate injection is for intravenous use only.

- •

- Administer cisatracurium besylate injection in carefully adjusted dosage by or under the supervision of experienced clinicians who are familiar with the drug’s actions and the possible complications.

- •

- Use cisatracurium besylate injection only if the following are immediately available: personnel and facilities for resuscitation and life support (tracheal intubation, artificial ventilation, oxygen therapy); and an antagonist of cisatracurium besylate injection [see Overdosage (10)].

- •

- The dosage information which follows is intended to serve as an initial guide for individual patients; base subsequent cisatracurium besylate dosage on the patients’ responses to the initial doses.

- •

- Use a peripheral nerve stimulator to:

- o

- Determine the adequacy of neuromuscular blockade (e.g., need for additional cisatracurium besylate injection doses, reduction of the infusion rate).

- o

- Minimize risk of overdosage or underdosage.

- o

- Assess the extent of recovery from neuromuscular blockade (e.g., spontaneous recovery or recovery after administration of a reversal agent, e.g., neostigmine).

- o

- Appropriately titrate doses to potentially limit exposure to toxic metabolites.

- o

- Facilitate more rapid reversal of the cisatracurium besylate injection-induced paralysis.

2.2 Recommended Cisatracurium Besylate Injection Dose for Performing Tracheal Intubation

Tracheal Intubation in Adults

Prior to selecting the initial cisatracurium besylate injection bolus dose, consider the desired time to tracheal intubation and the anticipated length of surgery, factors affecting time to onset of complete neuromuscular block such as age and renal function, and factors that may influence intubation conditions such as the presence of co-induction agents (e.g., fentanyl and midazolam) and the depth of anesthesia.

In conjunction with a propofol/nitrous oxide/oxygen induction-intubation technique or a thiopental/nitrous oxide/oxygen induction-intubation technique, the recommended starting weight-based dose of cisatracurium besylate injection is between 0.15 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg administered by bolus intravenous injection. Doses up to 0.4 mg/kg have been safely administered by bolus intravenous injection to healthy patients and patients with serious cardiovascular disease [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)].

Patients with Neuromuscular Disease

The maximum recommended initial bolus dose of cisatracurium besylate injection is 0.02 mg/kg in patients with neuromuscular diseases (e.g., myasthenia gravis and myasthenic syndrome and carcinomatosis) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Geriatric Patients and Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease

Because the time to maximum neuromuscular blockade is approximately 1 minute slower in geriatric patients compared to younger patients (and in patients with end-stage renal disease than in patients with normal renal function), consider extending the interval between administering cisatracurium besylate injection and attempting intubation by at least 1 minute to achieve adequate intubation conditions in geriatric patients and patients with end-stage renal disease. A peripheral nerve stimulator should be used to determine the adequacy of muscle relaxation for the purposes of intubation and the timing and amounts of subsequent doses [see Use in Specific Populations (8.5, 8.6) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Tracheal Intubation in Pediatric Patients

Infants 1 to 23 Months of Age

The recommended dose of cisatracurium besylate injection for intubation of pediatric patients ages 1 month to 23 months is 0.15 mg/kg administered over 5 to 10 seconds. When administered during stable opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, 0.15 mg/kg of cisatracurium besylate injection produced maximum neuromuscular blockade in about 2 minutes (range: 1.3 to 4.3 minutes) with a clinically effective block (time to 25% recovery) for about 43 minutes (range: 34 to 58 minutes) [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Pediatric Patients 2 to 12 Years of Age

The recommended weight-based bolus dose of cisatracurium besylate injection for pediatric patients 2 to 12 years of age is 0.1 to 0.15 mg/kg administered over 5 to 10 seconds. When administered during stable opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate injection produced maximum neuromuscular blockade in an average of 2.8 minutes (range: 1.8 to 6.7 minutes) with a clinically effective block (time to 25% recovery) for 28 minutes (range: 21 to 38 minutes). When administered during stable opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, 0.15 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate injection produced maximum neuromuscular blockade in an average of about 3 minutes (range: 1.5 to 8 minutes) with a clinically effective block for 36 minutes (range: 29 to 46 minutes) [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

2.3 Recommended Maintenance Bolus Cisatracurium Besylate Injection Doses in Adult Surgical Procedures

Determine if maintenance bolus doses are needed based on clinical criteria including the response to peripheral nerve stimulation. The recommended maintenance bolus dose of cisatracurium besylate injection is 0.03 mg/kg; however, smaller or larger maintenance doses may be administered based on the required duration of action. Administer the first maintenance bolus dose starting:

- •

- 40 to 50 minutes after an initial dose of cisatracurium besylate injection 0.15 mg/kg;

- •

- 50 to 60 minutes after an initial dose of cisatracurium besylate injection 0.2 mg/kg.

For long surgical procedures using inhalational anesthetics administered with nitrous oxide/oxygen at the 1.25 MAC level for at least 30 minutes, consider administering less frequent maintenance bolus doses or lower maintenance bolus doses of cisatracurium besylate injection [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)]. No adjustment to the initial cisatracurium besylate injection maintenance bolus dose should be necessary when cisatracurium besylate injection is administered shortly after initiation of volatile agents or when used in patients receiving propofol anesthesia.

2.4 Dosage in Burn Patients

Burn patients have been shown to develop resistance to nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents; therefore, consider increasing the cisatracurium besylate injection dosages for intubation and maintenance [see Use in Specific Populations (8.8)].

2.5 Dosage for Continuous Infusion

Continuous Infusion for Surgical Procedures in Adults and Pediatric Patients

During extended surgical procedures, cisatracurium besylate injection may be administered by continuous infusion to adults and pediatric patients aged 2 or more years if patients have spontaneous recovery after the initial cisatracurium besylate injection bolus dose. Following recovery from neuromuscular blockade, it may be necessary to re-administer a bolus dose to quickly re-establish neuromuscular blockade prior to starting the continuous infusion.

If patients have had recovery of neuromuscular function, the recommended initial cisatracurium besylate injection infusion rate is 3 mcg/kg/minute [see Dosage and Administration (2.6)]. Subsequently reduce the rate to 1 to 2 mcg/kg/minute to maintain continuous neuromuscular blockade. Use peripheral nerve stimulation to assess the level of neuromuscular blockade and to appropriately titrate the cisatracurium besylate injection infusion rate. If no response is elicited to peripheral nerve stimulation, discontinue the infusion until a response returns.

Consider reducing the infusion rate by up to 30% to 40% when cisatracurium besylate injection is administered during stable isoflurane anesthesia for at least 30 minutes (administered with nitrous oxide/oxygen at the 1.25 MAC level) [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)]. Greater reductions in the cisatracurium besylate injection infusion rate may be required with longer durations of administration of isoflurane or with the administration of other inhalational anesthetics.

Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Surgery

Consider reducing the infusion rate in patients undergoing CABG with induced hypothermia to half the rate required during normothermia [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)]. Spontaneous recovery from neuromuscular block following discontinuation of cisatracurium besylate injection infusion is expected to proceed at a rate comparable to that following administration of a single bolus dose.

Continuous Infusion for Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit in Adults

During extended need for mechanical ventilation and skeletal muscle relaxation in the intensive care unit (ICU), cisatracurium besylate may be administered by continuous infusion to adults if a patient has spontaneous recovery of neuromuscular function after the initial cisatracurium besylate injection bolus dose. Following recovery from neuromuscular blockade, it may be necessary to re-administer a bolus dose to quickly re-establish neuromuscular blockade prior to starting the continuous infusion.

The recommended cisatracurium besylate injection infusion rate in adult patients in the ICU is 3 mcg/kg/minute (range: 0.5 to 10.2 mcg/kg/minute) [see Dosage and Administration (2.6)]. Use peripheral nerve stimulation to assess the level of neuromuscular blockade and to appropriately titrate the cisatracurium besylate injection infusion rate.

2.6 Rate Tables for Continuous Infusion

The intravenous infusion rate depends upon the cisatracurium besylate injection concentration, the desired dose, the patient's weight, and the contribution of the infusion solution to the fluid requirements of the patient. Tables 1 and 2 provide guidelines for the cisatracurium besylate injection infusion rate, in mL/hour (equivalent to microdrops/minute when 60 microdrops = 1 mL), in concentrations of 0.1 mg/mL or 0.4 mg/mL, respectively.

- Table 1. Cisatracurium Besylate Infusion Rates for Maintenance of Neuromuscular Blockade During Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia with a Concentration of 0.1 mg/mL

|

|||||

|

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

|

|

||||

|

6 |

9 |

12 |

18 |

30 |

|

27 |

41 |

54 |

81 |

135 |

|

42 |

63 |

84 |

126 |

210 |

|

60 |

90 |

120 |

180 |

300 |

- Table 2. Cisatracurium Besylate Infusion Rates for Maintenance of Neuromuscular Blockade During Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia with a Concentration of 0.4 mg/mL

|

|||||

|

1 |

1.5 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

|

|

||||

|

1.5 |

2.3 |

3 |

4.5 |

7.5 |

|

6.8 |

10.1 |

13.5 |

20.3 |

33.8 |

|

|

15.8 |

21 |

31.5 |

52.5 |

|

15 |

22.5 |

30 |

45 |

75 |

2.7 Preparation of Cisatracurium Besylate Injection

Visually inspect cisatracurium besylate injection for particulate matter and discoloration prior to administration. If a cisatracurium besylate injection solution is cloudy or contains visible particulates, do not use cisatracurium besylate injection. Cisatracurium besylate injection is a colorless to slightly yellow or greenish-yellow solution.

Discard unused portion.

Cisatracurium besylate injection may be diluted to 0.1 mg/mL in the following solutions:

- •

- 5% Dextrose Injection, USP

- •

- 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP, or

- •

- 5% Dextrose and 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP

Store these diluted cisatracurium besylate injection solutions either in a refrigerator or at room temperature for 24 hours without significant loss of potency.

Cisatracurium besylate injection also may be diluted to 0.1 mg/mL or 0.2 mg/mL in the following solution:

- •

- Lactated Ringer’s and 5% Dextrose Injection

Store this diluted cisatracurium besylate injection solution under refrigeration for no more than 24 hours.

Do not dilute cisatracurium besylate injection in Lactated Ringer’s Injection, USP due to chemical instability.

2.8 Drug Compatibility

Cisatracurium besylate injection is compatible and may be administered with the following solutions through Y-site administration:

- •

- 5% Dextrose Injection, USP

- •

- 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP

- •

- 5% Dextrose and 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP

- •

- Sufentanil Citrate Injection, diluted as directed

- •

- Alfentanil Hydrochloride Injection, diluted as directed

- •

- Fentanyl Citrate Injection, diluted as directed

- •

- Midazolam Hydrochloride Injection, diluted as directed

- •

- Droperidol Injection, diluted as directed

Cisatracurium besylate injection is acidic (pH = 3.25 to 3.65) and may not be compatible with alkaline solution having a pH greater than 8.5 (e.g., barbiturate solutions). Therefore, do not administer cisatracurium besylate injection and alkaline solutions simultaneously in the same intravenous line.

Cisatracurium besylate injection is not compatible with propofol injection or ketorolac injection for Y-site administration. Compatibility studies with other parenteral products have not been conducted.

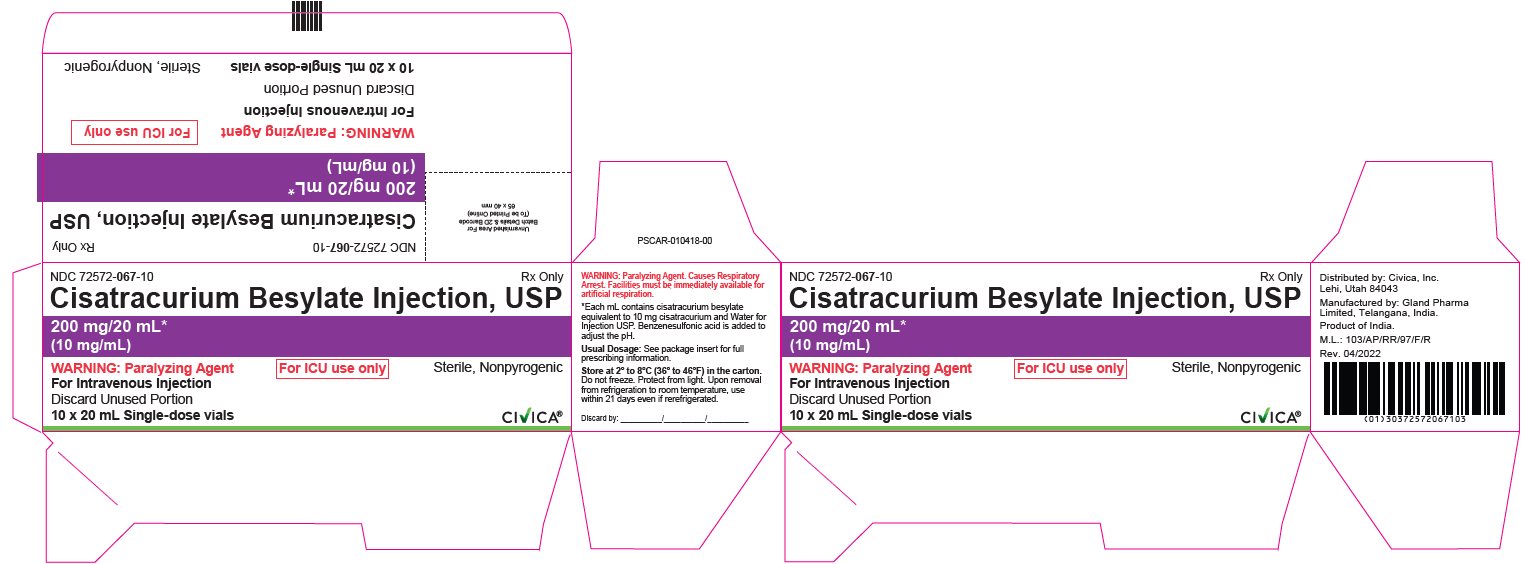

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Cisatracurium besylate injection, USP is available as a clear solution in the following strength:

- •

- 200 mg of cisatracurium per 20 mL (10 mg/mL) in single-dose vials (equivalent to 13.38 mg/mL cisatracurium besylate); intended only for administration as an infusion in a single patient in the ICU.

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

- •

- Cisatracurium besylate injection is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to cisatracurium. Severe anaphylactic reactions to cisatracurium besylate have been reported [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Residual Paralysis

Cisatracurium besylate has been associated with residual paralysis. Patients with neuromuscular diseases (e.g., myasthenia gravis and myasthenic syndrome) and carcinomatosis may be at higher risk of residual paralysis; thus, a lower maximum initial bolus is recommended in these patients [see Dosage and Administration (2.2) and Use in Specific Populations (8.10)]. To prevent complications resulting from cisatracurium besylate-associated residual paralysis, extubation is recommended only after the patient has recovered sufficiently from neuromuscular blockade. Consider use of a reversal agent especially in cases where residual paralysis is more likely to occur [see Overdosage (10)].

5.3 Risk of Seizure

Laudanosine, an active metabolite of cisatracurium besylate, has been shown to cause seizures in animals. Cisatracurium besylate-treated patients with renal or hepatic impairment may have higher metabolite concentrations (including laudanosine) than patients with normal renal and hepatic function [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Therefore, patients with renal or hepatic impairment receiving extended administration of cisatracurium besylate may be at higher risk of seizures.

The level of neuromuscular blockade during long-term cisatracurium besylate administration should be monitored with a nerve stimulator to titrate cisatracurium besylate administration to the patients’ needs and limit exposure to toxic metabolites.

5.4 Hypersensitivity Reactions Including Anaphylaxis

Severe hypersensitivity reactions, including fatal and life-threatening anaphylactic reactions, have been reported [see Contraindications (4)]. There have been reports of wheezing, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, rash and itching following cisatracurium besylate administration in pediatric patients. Due to the potential severity of these reactions, appropriate precautions such as the immediate availability of appropriate emergency treatment should be taken. Precautions should also be taken in those patients who have had previous anaphylactic reactions to other neuromuscular blocking agents since cross-reactivity between neuromuscular blocking agents, both depolarizing and non-depolarizing, has been reported.

5.5 Risk of Death Due to Medication Errors

Administration of cisatracurium besylate results in paralysis, which may lead to respiratory arrest and death, a progression that may be more likely to occur in a patient for whom it is not intended. Confirm proper selection of intended product and avoid confusion with other injectable solutions that are present in critical care and other clinical settings. If another healthcare provider is administering the product, ensure that the intended dose is clearly labeled and communicated.

5.6 Risks Due to Inadequate Anesthesia

Neuromuscular blockade in the conscious patient can lead to distress. Use cisatracurium besylate in the presence of appropriate sedation or general anesthesia. Monitor patients to ensure that the level of anesthesia is adequate.

5.7 Risk for Infection

The 20 mL vial of cisatracurium besylate is intended only for administration as an infusion for use in a single patient in the ICU. The 20 mL vial should not be used multiple times because there is a higher risk of infection (the 20 mL vial does not contain a preservative).

5.8 Potentiation of Neuromuscular Blockade

Certain drugs may enhance the neuromuscular blocking action of cisatracurium besylate including inhalational anesthetics, antibiotics, magnesium salts, lithium, local anesthetics, procainamide and quinidine [see Drug Interactions (7.1)]. Additionally, acid-base and/or serum electrolyte abnormalities may potentiate the action of neuromuscular blocking agents. Use peripheral nerve stimulation and monitor the clinical signs of neuromuscular blockade to determine the adequacy of the level of neuromuscular blockage and the need to adjust the cisatracurium besylate dosage.

5.9 Resistance to Neuromuscular Blockade with Certain Drugs

Shorter durations of neuromuscular block may occur and cisatracurium besylate infusion rate requirements may be higher in patients chronically administered phenytoin or carbamazepine [see Drug Interactions (7.1) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Use peripheral nerve stimulation and monitor the clinical signs of neuromuscular blockade to determine the adequacy of neuromuscular blockage and the need to adjust the cisatracurium besylate dosage.

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Studies Experience

Because clinical studies are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical studies of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical studies of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials of Cisatracurium Besylate in Surgical Patients

The data presented below are based on studies involving 945 surgical patients who received cisatracurium besylate in conjunction with other drugs in US and European clinical studies in a variety of procedures [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

Table 3 displays adverse reactions that occurred at a rate of less than 1%.

Table 3. Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials of Cisatracurium Besylate in Surgical Patients

|

Incidence |

|

0.4% |

|

0.2% |

|

0.2% |

|

0.2% |

|

0.1% |

Adverse Reactions in Clinical Trials of Cisatracurium Besylate in Intensive Care Unit Patients

The adverse reactions presented below were from studies involving 68 adult ICU patients who received cisatracurium besylate in conjunction with other drugs in US and European clinical studies [see Clinical Studies (14.3)]. One patient experienced bronchospasm. In one of the two ICU studies, a randomized and double-blind study of ICU patients using TOF neuromuscular monitoring, there were two reports of prolonged recovery (range: 167 and 270 minutes) among 28 patients administered cisatracurium besylate and 13 reports of prolonged recovery (range: 90 minutes to 33 hours) among 30 patients administered vecuronium.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following events have been identified during post-approval use of cisatracurium besylate in conjunction with one or more anesthetic agents in clinical practice. Because they are reported voluntarily from a population of unknown size, estimates of frequency cannot be made. These events have been chosen for inclusion due to a combination of their seriousness, frequency of reporting, or potential causal connection to cisatracurium besylate: anaphylaxis, histamine release, prolonged neuromuscular block, muscle weakness, myopathy.

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Clinically Significant Drug Interactions

Table 4 displays clinically significant drug interactions with cisatracurium besylate.

Table 4. Clinically Significant Drug Interactions with Cisatracurium Besylate

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Risk Summary

There are no available clinical trial data on cisatracurium use in pregnancy to evaluate a drug associated risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes. Animal studies conducted in rats administered cisatracurium besylate during organogenesis (Gestational Day 6 to 15) found no evidence of fetal harm at 0.8 times (ventilated rats) the exposure from a human starting IV bolus dose of 0.2 mg/kg (see Data).

The estimated background risk for major birth defects and miscarriage in the indicated population is unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defect, loss, or other adverse outcomes. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2-4% and 15-20%, respectively.

Clinical Considerations

Labor or Delivery

The action of neuromuscular blocking agents may be enhanced by magnesium salts administered for the management of preeclampsia or eclampsia of pregnancy.

Data

Animal Data

Two embryofetal developmental reproductive toxicity studies were conducted in rats. In a non-ventilated rat study, pregnant animals were treated with cisatracurium besylate subcutaneously twice per day from Gestational Day 6 to 15 using subparalyzing doses (2 and 4 mg/kg daily; equivalent to 6- and 12-times, respectively, the AUC exposure in humans following a bolus dose of 0.2 mg/kg IV). In the ventilated rat study, pregnant animals were treated with cisatracurium besylate intravenously once a day between Gestational Day 6 to 15 using paralyzing doses (0.5 and 1 mg/kg; equivalent to 0.4- and 0.8-times, respectively, the exposure in humans following a bolus dose of 0.2 mg/kg IV based on mg/m2 comparison). Neither of these studies revealed maternal or fetal toxicity or malformations.

8.2 Lactation

There are no data on the presence of cisatracurium besylate in human milk, the effects on the breastfed child, or the effects on milk production. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother's clinical need for cisatracurium besylate and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed child from cisatracurium besylate or from the underlying maternal condition.

8.4 Pediatric Use

The safety and effectiveness of cisatracurium besylate as an adjunct to general anesthesia to facilitate tracheal intubation, and to provide skeletal muscle relaxation during surgery in pediatric patients 1 month through 12 years of age were established from three studies in pediatric patients [see Dosing and Administration (2.2, 2.5) and Clinical Studies (14.2)]. The three open-label studies are summarized below.

The safety and effectiveness of cisatracurium besylate have not been established in pediatric patients less than 1 month of age.

Tracheal Intubation

A study of 0.15 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate evaluated 230 pediatric patients (ages 1 month to 12 years). Excellent or good intubating conditions were produced 120 seconds following 0.15 mg/kg of cisatracurium besylate in 88 of 90 of patients induced with halothane and in 85 of 90 of patients induced with thiopentone and fentanyl. The study also evaluated 50 pediatric patients during opioid anesthesia, with maximum neuromuscular blockade achieved in an average of about 3 minutes and a clinically effective block for 36 minutes in patients ages 2 to 12 years, and maximum neuromuscular block in about 2 minutes and a clinically effective block for about 43 minutes in infants 1 to 23 months [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

In a study of 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate administered in 16 pediatric patients (ages 2 to 12 years) during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, maximum neuromuscular blockade was achieved in an average of 2.8 minutes with a clinically effective block for 28 minutes [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

Skeletal Muscle Relaxation During Surgery

In a study of cisatracurium besylate administered during halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, 18 pediatric patients (ages 2 to 12 years) were scheduled for surgical procedures that required neuromuscular block for 60 minutes or longer. The average duration of continuous infusion was 62.8 minutes (range: 17 to 145 minutes). The overall mean infusion rate for 9 patients whose infusion was 45 minutes or longer was 1.7 mcg/kg/minute (range: 1.19 to 2.14 mcg/kg/minute).

8.5 Geriatric Use

Of the total number of subjects (135) in clinical studies of cisatracurium besylate, 57, 63, and 15 subjects were 65 to 70 years old, 70 to 80 years old, and greater than 80 years old, respectively. The geriatric population included a subset of patients with significant cardiovascular disease [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Because the time to maximum neuromuscular blockade is approximately 1 minute slower in geriatric patients compared to younger patients, consider extending the interval between administering cisatracurium besylate and attempting intubation by at least 1 minute to achieve adequate intubation conditions [see Dosage and Administration (2.2) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)].

The time to maximum neuromuscular blockade is approximately 1 minute slower in geriatric patients, a difference that should be taken into account when selecting a neuromuscular blocking agent (e.g., the need to rapidly secure the airway) and when initiating laryngoscopy [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. Minor differences in the pharmacokinetics of cisatracurium between elderly and young adult patients were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate following a single 0.1 mg/kg dose.

Besides the differences noted above, no overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between geriatric and younger subjects, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between geriatric and younger subjects, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals to cisatracurium besylate cannot be ruled out.

8.6 Patients with Renal Impairment

The time to 90% neuromuscular blockade was 1 minute slower in patients with end-stage renal disease than in patients with normal renal function. Therefore, consider extending the interval between administering cisatracurium besylate and attempting intubation by at least 1 minute to achieve adequate intubation conditions [see Dosage and Administration (2.2) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.2)].

There was no clinically significant alteration in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate in patients with end-stage renal disease following a 0.1 mg/kg dose of cisatracurium besylate. The recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate is unchanged in patients with renal impairment, which is consistent with predominantly organ-independent elimination [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.7 Patients with Hepatic Impairment

The pharmacokinetic study analysis in patients with end-stage liver disease undergoing liver transplantation and healthy subjects undergoing elective surgery indicated slightly larger volumes of distribution in liver transplant patients with slightly higher plasma clearances of cisatracurium. The times to maximum neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute faster in liver transplant patients than in healthy adult patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. These minor differences in pharmacokinetics were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.8 Burn Patients

Patients with burns have been shown to develop resistance to nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents. The extent of altered response depends upon the size of the burn and the time elapsed since the burn injury. Cisatracurium besylate has not been studied in patients with burns. However, based on its structural similarity to another neuromuscular blocking agent, consider the possibility of increased dosage requirements and shortened duration of action if cisatracurium besylate is administered to burn patients.

8.9 Patients with Hemiparesis or Paraparesis

Patients with hemiparesis or paraparesis may demonstrate resistance to nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents in the affected limbs. To avoid inaccurate dosing, perform neuromuscular monitoring on a non-paretic limb.

8.10 Patients with Neuromuscular Disease

Profound and prolonged neuromuscular blockade may occur in patients with neuromuscular diseases (e.g., myasthenia gravis and myasthenic syndrome) and carcinomatosis. Therefore, a lower maximum initial bolus is recommended in these patients [see Dosage and Administration (2.2)].

10 OVERDOSAGE

Overdosage with neuromuscular blocking agents may result in neuromuscular blockade beyond the time needed for surgery and anesthesia. The primary treatment is maintenance of a patent airway and controlled ventilation until recovery of normal neuromuscular function is assured.

Once recovery from neuromuscular block begins, further recovery may be facilitated by administration of a cholinesterase inhibitor (e.g., neostigmine, edrophonium) in conjunction with an appropriate cholinergic inhibitor. Cholinesterase inhibitors should not be administered when complete neuromuscular blockade is evident or suspected because the reversal of paralysis may not be sufficient to maintain a patent airway and support an appropriate level of spontaneous ventilation.

- •

- Neostigmine: Administration of 0.04 to 0.07 mg/kg of neostigmine at approximately 10% recovery from neuromuscular blockade (range: 0 to 15%) produced 95% recovery of the muscle twitch response and a T4:T1 ratio ≥ 70% in an average of 9 to 10 minutes. The times from 25% recovery of the muscle twitch response to a T4:T1 ratio ≥ 70% following these doses of neostigmine averaged 7 minutes. The mean 25% to 75% recovery index following reversal was 3 to 4 minutes.

- •

- Edrophonium: Administration of 1 mg/kg of edrophonium at approximately 25% recovery from neuromuscular blockade (range: 16% to 30%) produced 95% recovery and a T4:T1 ratio ≥ 70% in an average of 3 to 5 minutes.

For providers treating patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors:

- •

- Use a peripheral nerve stimulator to evaluate recovery and antagonism of neuromuscular blockade

- •

- Evaluate for evidence of adequate clinical recovery (e.g., 5-second head lift and grip strength).

- •

- Support ventilation until adequate spontaneous ventilation has resumed.

The onset of antagonism may be delayed in the presence of debilitation, cachexia, carcinomatosis, and the concomitant use of certain broad spectrum antibiotics, or anesthetic agents and other drugs which enhance neuromuscular block or separately cause respiratory depression [see Drug Interactions (7.1)]. Under such circumstances the management is the same as that of prolonged neuromuscular block.

11 DESCRIPTION

Cisatracurium besylate is a nondepolarizing skeletal neuromuscular blocker for intravenous administration. Compared to other neuromuscular blockers, it is intermediate in its onset and duration of action. Cisatracurium besylate injection, USP contains cisatracurium besylate as the active pharmaceutical ingredient.

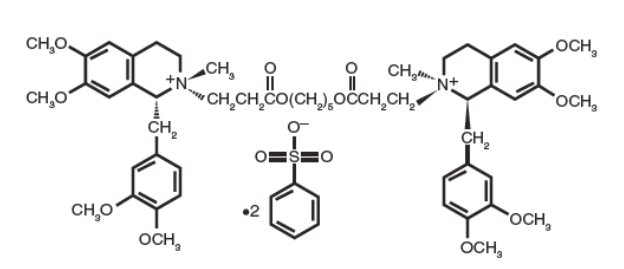

Cisatracurium besylate is one of 10 isomers of atracurium besylate and constitutes approximately 15% of that mixture. Cisatracurium besylate is [1R-[1α,2α(1'R*,2'R*)]]-2,2'-[1,5-pentanediylbis[oxy(3-oxo-3,1-propanediyl)]]bis[1-[(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6,7-dimethoxy-2-methylisoquinolinium] dibenzenesulfonate. The molecular formula of the cisatracurium parent bis-cation is C53H72N2O12 and the molecular weight is 929.2. The molecular formula of cisatracurium as the besylate salt is C65H82N2O18S2 and the molecular weight is 1243.50. The structural formula of cisatracurium besylate is:

The log of the partition coefficient of cisatracurium besylate is -2.12 in a 1-octanol/distilled water system at 25°C.

Cisatracurium besylate injection, USP is a sterile, non-pyrogenic aqueous solution provided in a 20 mL vial. The pH is adjusted to 3.25 to 3.65 with benzenesulfonic acid. The 20 mL vial, intended for ICU use only, contains cisatracurium besylate, equivalent to 10 mg/mL cisatracurium. The 20 mL vial is a single-dose vial and does not contain benzyl alcohol.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

Cisatracurium besylate binds competitively to cholinergic receptors on the motor end-plate to antagonize the action of acetylcholine, resulting in blockade of neuromuscular transmission. This action is antagonized by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

The average ED95 (dose required to produce 95% suppression of the adductor pollicis muscle twitch response to ulnar nerve stimulation) of cisatracurium is 0.05 mg/kg (range: 0.048 to 0.053) in adults receiving opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia.

The pharmacodynamics of various cisatracurium besylate doses administered over 5 to 10 seconds during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia are summarized in Table 5. When the cisatracurium besylate dose is doubled, the clinically effective duration of blockade increases by approximately 25 minutes. Once recovery begins, the rate of recovery is independent of dose.

Isoflurane or enflurane administered with nitrous oxide/oxygen to achieve 1.25 MAC (Minimum Alveolar Concentration) prolonged the clinically effective duration of action of initial and maintenance cisatracurium besylate doses, and decreased the average infusion rate requirement of cisatracurium besylate. The magnitude of these effects depended on the duration of administration of the volatile agents:

- •

- Fifteen to 30 minutes of exposure to 1.25 MAC isoflurane or enflurane had minimal effects on the duration of action of initial doses of cisatracurium besylate.

- •

- In surgical procedures during enflurane or isoflurane anesthesia greater than 30 minutes, less frequent maintenance dosing, lower maintenance doses, or reduced infusion rates of cisatracurium besylate were required. The average infusion rate requirement was decreased by as much as 30% to 40% [see Drug Interactions (7.1)].

The onset, duration of action, and recovery profiles of cisatracurium besylate during propofol/oxygen or propofol/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia were similar to those during opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia (see Table 5).

Repeated administration of maintenance cisatracurium besylate doses or a continuous cisatracurium besylate infusion for up to 3 hours was not associated with development of tachyphylaxis or cumulative neuromuscular blocking effects. The time needed to recover from successive maintenance doses did not change with the number of doses administered when partial recovery occurred between doses. The rate of spontaneous recovery of neuromuscular function after cisatracurium besylate infusion was independent of the duration of infusion and comparable to the rate of recovery following initial doses (see Table 5).

Pediatric patients including infants generally had a shorter time to maximum neuromuscular blockade and a faster recovery from neuromuscular blockade compared to adults treated with the same weight-based doses (see Table 5).

- Table 5. Pharmacodynamic Dose Response* of Cisatracurium Besylate During Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia

|

|

|

5%

|

25%

|

95%

|

T4:T1

|

|

|

|||||||

|

3.3 |

5.0 |

33 |

42 |

64 |

64 |

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

2.6 |

3.5 |

46 |

55 |

76 |

75 |

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

2.4 |

2.9 |

59 |

65 |

81 |

85 |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

1.6 |

2.0 |

70 |

78 |

91 |

97 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

1.5 |

1.9 |

83 |

91 |

121 |

126 |

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

1.5 |

2.0 |

36 |

43 |

64 |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

2.2 |

3.3 |

22 |

29 |

52 |

50 |

11 |

|

¶ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

1.7 |

2.8 |

21 |

28 |

46 |

44 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.1 |

3.0 |

29 |

36 |

55 |

54 |

|

|

** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

Hemodynamics Profile

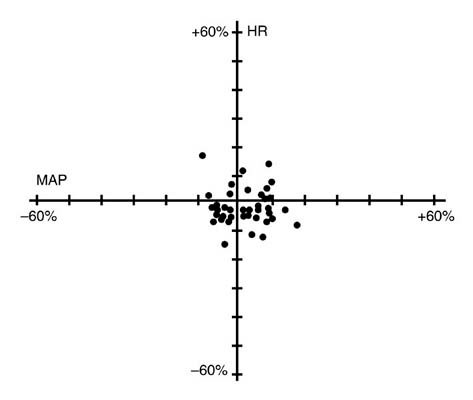

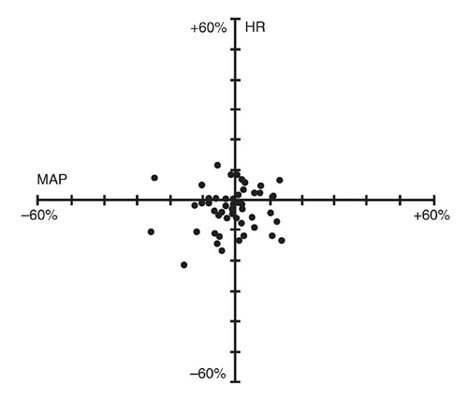

Cisatracurium besylate had no dose-related effects on mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) or heart rate (HR) following doses ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg, administered over 5 to 10 seconds, in healthy adult patients (see Figure 1) or in patients with serious cardiovascular disease (see Figure 2).

A total of 141 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery were administered cisatracurium besylate in three active-controlled clinical trials and received doses ranging from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.4 mg/kg. While the hemodynamic profile was comparable in both the cisatracurium besylate and active control groups, data for doses above 0.3 mg/kg in this population are limited.

- Figure 1. Maximum Percent Change from Preinjection in HR and MAP During First 5 Minutes after Initial 4 × ED95 to 8 × ED95 Cisatracurium Besylate Doses in Healthy Adults Who Received Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia (n=44)

- Figure 2. Percent Change from Preinjection in HR and MAP 10 Minutes After an Initial 4 × ED95 to 8 × ED95 Cisatracurium Besylate Dose in Patients Undergoing CABG Surgery Receiving Oxygen/Fentanyl/Midazolam/Anesthesia (n=54)

No clinically significant changes in MAP or HR were observed following administration of doses up to 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate over 5 to 10 seconds in 2- to 12-year-old pediatric patients who received either halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen or opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia. Doses of 0.15 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate administered over 5 seconds were not consistently associated with changes in HR and MAP in pediatric patients aged 1 month to 12 years who received opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen or halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

The neuromuscular blocking activity of cisatracurium besylate is due to parent drug. Cisatracurium plasma concentration-time data following IV bolus administration are best described by a two-compartment open model (with elimination from both compartments) with an elimination half- life (t½β) of 22 minutes, a plasma clearance (CL) of 4.57 mL/min/kg, and a volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) of 145 mL/kg.

Results from population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analyses from 241 healthy surgical patients are summarized in Table 6.

- Table 6. Key Population PK/PD Parameter Estimates for Cisatracurium in Healthy Surgical Patients* Following 0.1 (2 × ED95) to 0.4 mg/kg (8 × ED95) of Cisatracurium Besylate

|

|

Magnitude of Interpatient Variability (CV)‡ |

|

4.57 |

16% |

|

145 |

27% |

|

0.0575 |

61% |

|

141 |

52% |

|

||

The magnitude of interpatient variability in CL was low (16%), as expected based on the importance of Hofmann elimination. The magnitudes of interpatient variability in CL and volume of distribution were low in comparison to those for keo and EC50. This suggests that any alterations in the time course of cisatracurium besylate-induced neuromuscular blockade were more likely to be due to variability in the PD parameters than in the PK parameters. Parameter estimates from the population PK analyses were supported by noncompartmental PK analyses on data from healthy patients and from specific populations.

Conventional PK analyses have shown that the PK of cisatracurium are proportional to dose between 0.1 (2 × ED95) and 0.2 (4 × ED95) mg/kg cisatracurium. In addition, population PK analyses revealed no statistically significant effect of initial dose on CL for doses between 0.1 (2 × ED95) and 0.4 (8 × ED95) mg/kg cisatracurium.

Distribution

The volume of distribution of cisatracurium is limited by its large molecular weight and high polarity. The Vss was equal to 145 mL/kg (Table 6) in healthy 19- to 64-year-old surgical patients receiving opioid anesthesia. The Vss was 21% larger in similar patients receiving inhalation anesthesia.

The binding of cisatracurium to plasma proteins has not been successfully studied due to its rapid degradation at physiologic pH. Inhibition of degradation requires nonphysiological conditions of temperature and pH which are associated with changes in protein binding.

Elimination

Organ-independent Hofmann elimination (a chemical process dependent on pH and temperature) is the predominant pathway for the elimination of cisatracurium. The liver and kidney play a minor role in the elimination of cisatracurium but are primary pathways for the elimination of metabolites. Therefore, the t½β values of metabolites (including laudanosine) are longer in patients with renal or hepatic impairment and metabolite concentrations may be higher after long-term administration [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

The mean CL values for cisatracurium ranged from 4.5 to 5.7 mL/min/kg in studies of healthy surgical patients. The compartmental PK modeling suggests that approximately 80% of the cisatracurium CL is accounted for by Hofmann elimination and the remaining 20% by renal and hepatic elimination. These findings are consistent with the low magnitude of interpatient variability in CL (16%) estimated as part of the population PK/PD analyses and with the recovery of parent and metabolites in urine.

In studies of healthy surgical patients, mean t½β values of cisatracurium ranged from 22 to 29 minutes and were consistent with the t½β of cisatracurium in vitro (29 minutes). The mean ± SD t½β values of laudanosine were 3.1 ± 0.4 hours in healthy surgical patients receiving cisatracurium besylate (n=10).

Metabolism

The degradation of cisatracurium was largely independent of liver metabolism. Results from in vitro experiments suggest that cisatracurium undergoes Hofmann elimination (a pH and temperature-dependent chemical process) to form laudanosine [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] and the monoquaternary acrylate metabolite, neither of which has any neuromuscular blocking activity. The monoquaternary acrylate undergoes hydrolysis by non-specific plasma esterases to form the monoquaternary alcohol (MQA) metabolite. The MQA metabolite can also undergo Hofmann elimination but at a much slower rate than cisatracurium. Laudanosine is further metabolized to desmethyl metabolites which are conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted in the urine.

The laudanosine metabolite of cisatracurium has been noted to cause transient hypotension and, in higher doses, cerebral excitatory effects when administered to several animal species. The relationship between CNS excitation and laudanosine concentrations in humans has not been established [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

During IV infusions of cisatracurium besylate, peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of laudanosine and the MQA metabolite were approximately 6% and 11% of the parent compound, respectively. The Cmax values of laudanosine in healthy surgical patients receiving infusions of cisatracurium besylate were mean ± SD Cmax: 60 ± 52 ng/mL.

Excretion

Following 14C-cisatracurium administration to 6 healthy male patients, 95% of the dose was recovered in the urine (mostly as conjugated metabolites) and 4% in the feces; less than 10% of the dose was excreted as unchanged parent drug in the urine. In 12 healthy surgical patients receiving non-radiolabeled cisatracurium who had Foley catheters placed for surgical management, approximately 15% of the dose was excreted unchanged in the urine.

Special Populations

Geriatric Patients

The results of conventional PK analysis from a study of 12 healthy elderly patients and 12 healthy young adult patients who received a single IV cisatracurium besylate dose of 0.1 mg/kg are summarized in Table 7. Plasma clearances of cisatracurium were not affected by age; however, the volumes of distribution were slightly larger in elderly patients than in young patients resulting in slightly longer t½β values for cisatracurium.

The rate of equilibration between plasma cisatracurium concentrations and neuromuscular blockade was slower in elderly patients than in young patients (mean ± SD keo: 0.071 ± 0.036 and 0.105 ± 0.021 minutes-1, respectively); there was no difference in the patient sensitivity to cisatracurium-induced block, as indicated by EC50 values (mean ± SD EC50: 91 ± 22 and 89 ± 23 ng/mL, respectively). These changes were consistent with the 1-minute slower times to maximum block in elderly patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate, when compared to young patients receiving the same dose. The minor differences in PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium between elderly patients and young patients were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

- Table 7. Pharmacokinetic Parameters* of Cisatracurium in Healthy Elderly and Young Adult Patients Following 0.1 mg/kg (2 × ED95) of Cisatracurium Besylate (Isoflurane/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Patients with Hepatic Impairment

Table 8 summarizes the conventional PK analysis from a study of cisatracurium besylate in 13 patients with end-stage liver disease undergoing liver transplantation and 11 healthy adult patients undergoing elective surgery. The slightly larger volumes of distribution in liver transplant patients were associated with slightly higher plasma clearances of cisatracurium. The parallel changes in these parameters resulted in no difference in t½β values. There were no differences in keo or EC50 between patient groups. The times to maximum neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute faster in liver transplant patients than in healthy adult patients receiving 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. These minor PK differences were not associated with clinically significant differences in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

The t½β values of metabolites are longer in patients with hepatic disease and concentrations may be higher after long-term administration.

- Table 8. Pharmacokinetic Parameters* of Cisatracurium in Healthy Adult Patients and in Patients Undergoing Liver Transplantation Following 0.1 mg/kg (2 × ED95) of Cisatracurium Besylate (Isoflurane/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia)

|

|

|

|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) |

|

|

|

Volume of Distribution at Steady State‡ (mL/kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Patients with Renal Impairment

Results from a conventional PK study of cisatracurium besylate in 13 healthy adult patients and 15 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who had elective surgery are summarized in Table 9. The PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium were similar in healthy adult patients and ESRD patients. The times to 90% neuromuscular blockade were approximately one minute slower in ESRD patients following 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. There were no differences in the durations or rates of recovery of cisatracurium besylate between ESRD and healthy adult patients.

The t½β values of metabolites are longer in patients with ESRD and concentrations may be higher after long-term administration.

Population PK analyses showed that patients with creatinine clearances ≤70 mL/min had a slower rate of equilibration between plasma concentrations and neuromuscular block than patients with normal renal function; this change was associated with a slightly slower (~ 40 seconds) predicted time to 90% T1 suppression in patients with renal impairment following 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate. There was no clinically significant alteration in the recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate in patients with renal impairment. The recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate is unchanged in the presence of renal or hepatic failure, which is consistent with predominantly organ-independent elimination.

- Table 9. Pharmacokinetic Parameters* for Cisatracurium in Healthy Adult Patients and in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Who Received 0.1 mg/kg (2 × ED95) of Cisatracurium Besylate (Opioid/Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Anesthesia)

|

|

|

|

Elimination Half-Life (t½β, min) |

|

|

|

149 ± 35 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Patients

The PK of cisatracurium and its metabolites were determined in six ICU patients who received cisatracurium besylate and are presented in Table 10. The relationships between plasma cisatracurium concentrations and neuromuscular blockade have not been evaluated in ICU patients.

Limited PK data are available for ICU patients with hepatic or renal impairment who received cisatracurium besylate. Relative to cisatracurium besylate-treated ICU patients with normal renal and hepatic function, metabolite concentrations (plasma and tissues) may be higher in cisatracurium besylate-treated ICU patients with renal or hepatic impairment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

- Table 10. Parameter Estimates* for Cisatracurium and Metabolites in ICU Patients After Long-Term (24 to 48 Hour) Administration of Cisatracurium Besylate

|

|

|

|

|

7.45 ± 1.02 |

|

t½β (min) |

26.8 ± 11.1 |

|

|

Vβ (mL/kg)† |

280 ± 103 |

|

|

Cmax (ng/mL) |

707 ± 360 |

|

t½β (hrs) |

6.6 ± 4.1 |

|

|

|

152-181‡ |

|

26-31‡ |

|

|

||

Pediatric Population

The population PK/PD of cisatracurium were described in 20 healthy pediatric patients ages 2 to 12 years during halothane anesthesia, using the same model developed for healthy adult patients. The CL was higher in healthy pediatric patients (5.89 mL/min/kg) than in healthy adult patients (4.57 mL/min/kg) during opioid anesthesia. The rate of equilibration between plasma concentrations and neuromuscular blockade, as indicated by keo, was faster in healthy pediatric patients receiving halothane anesthesia (0.1330 minutes-1) than in healthy adult patients receiving opioid anesthesia (0.0575 minutes-1). The EC50 in healthy pediatric patients (125 ng/mL) was similar to the value in healthy adult patients (141 ng/mL) during opioid anesthesia. The minor differences in the PK/PD parameters of cisatracurium were associated with a faster time to onset and a shorter duration of cisatracurium-induced neuromuscular blockade in pediatric patients.

Sex and Obesity

Although population PK/PD analyses revealed that sex and obesity were associated with effects on the PK and/or PD of cisatracurium; these PK/PD changes were not associated with clinically significant alterations in the predicted onset or recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate.

Use of Inhalation Agents

The use of inhalation agents was associated with a 21% larger Vss, a 78% larger keo, and a 15% lower EC50 for cisatracurium. These changes resulted in a slightly faster (~ 45 seconds) predicted time to 90% T1 suppression in patients who received 0.1 mg/kg cisatracurium during inhalation anesthesia than in patients who received the same dose of cisatracurium during opioid anesthesia; however, there were no clinically significant differences in the predicted recovery profile of cisatracurium besylate between patient groups.

Drug Interaction Studies

Carbamazepine and phenytoin

The systemic clearance of cisatracurium was higher in patients who were on prior chronic anticonvulsant therapy of carbamazepine or phenytoin [see Warning and Precautions (5.9) and Drug Interactions (7.1)].

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Long-term animal studies to evaluate the carcinogenic potential of cisatracurium besylate have not been performed.

Mutagenesis

Cisatracurium besylate was evaluated in a battery of four genotoxicity assays. Evaluation of cisatracurium besylate in the in vitro mouse lymphoma forward gene mutation assay resulted in mutations in the presence and absence of exogenous metabolic activation. The in vitro bacterial reverse gene mutation (Ames) assay, in vitro human lymphocyte chromosomal aberration assay, and an in vivo rat bone marrow cytogenetic assay did not demonstrate evidence of mutagenicity or clastogenicity.

Impairment of Fertility

Studies to determine if cisatracurium besylate impacts fertility have not been completed.

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Skeletal Muscle Relaxation for Intubation of Adult Patients

The efficacy of cisatracurium besylate to provide skeletal muscle relaxation to facilitate tracheal intubation during surgery was established in six studies in adult patients. In all these studies patients had general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation.

- •

- Cisatracurium besylate doses between 0.15 and 0.2 mg/kg were evaluated in 240 adults. Maximum neuromuscular blockade generally occurred in within 4 minutes for this dose range.

- •

- When administered during induction using thiopental or propofol and co-induction agents (i.e., fentanyl and midazolam), excellent to good intubating conditions were generally achieved within 2 minutes (excellent intubation conditions most frequently achieved with the 0.2 mg/kg dose of cisatracurium besylate).

- •

- Following the induction of general anesthesia with propofol, nitrous oxide/oxygen, and co-induction agents (e.g., fentanyl and midazolam), good or excellent conditions for tracheal intubation occurred in 96/102 (94%) patients in 1.5 to 2 minutes following cisatracurium besylate doses of 0.15 mg/kg and in 97/110 (88%) patients in 1.5 minutes following cisatracurium besylate doses of 0.2 mg/kg.

In Study 1, the clinically effective duration of action for 0.15 and 0.2 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate using propofol anesthesia was 55 minutes (range: 44 to 74 minutes) and 61 minutes (range: 41 to 81 minutes), respectively.

In Studies 2 and 3, cisatracurium besylate doses of 0.25 and 0.4 mg/kg were evaluated in 30 patients under opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia and provided 78 (66 to 86) and 91 (59 to 107) minutes of clinical relaxation, respectively.

In Study 4, two minutes after fentanyl and midazolam were administered, patients received thiopental anesthesia. Intubating conditions were assessed at 120 seconds following administration of 0.15 mg/kg or 0.2 mg/kg of cisatracurium besylate in 51 patients (see Table 11).

- Table 11. Intubating Conditions at 120 Seconds after Cisatracurium Besylate Administration with Thiopental Anesthesia in Adult Surgery Patients in Study 4

|

Cisatracurium Besylate 0.15 mg/kg (n=26) |

Cisatracurium Besylate 0.20 mg/kg (n=25) |

|

|

88% |

96% |

|

76,100 |

88,100 |

|

31% |

60% |

|

58% |

36% |

|

||

Excellent intubating conditions were more frequently achieved with the 0.2 mg/kg dose (60%) than the 0.15 mg/kg dose (31%) when intubation was attempted 120 seconds following cisatracurium besylate.

Study 5 evaluated intubating conditions after 3 and 4 × ED95 (0.15 mg/kg and 0.20 mg/kg) following induction with fentanyl and midazolam and either thiopental or propofol anesthesia. This study compared intubation conditions produced by these doses of cisatracurium besylate after 90 seconds. Table 12 displays these results.

- Table 12. Intubating Conditions at 90 Seconds after Cisatracurium Besylate Administration with Thiopental or Propofol Anesthesia in Study 5

|

|

(n=31) |

(n=30) |

|

|

94% |

|

93% |

96% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

58% |

|

70% |

57% |

|

35% |

|

20% |

39% |

- * Excellent: Easy passage of tube without coughing. Vocal cords relaxed and abducted.

- Good: Passage of tube with slight coughing and/or bucking. Vocal cords relaxed and abducted.

Excellent intubating conditions were more frequently observed with the 0.2 mg/kg dose when intubation was attempted 90 seconds following cisatracurium besylate.

14.2 Skeletal Muscle Relaxation for Intubation of Pediatric Patients

The efficacy of cisatracurium besylate to provide skeletal muscle relaxation to facilitate tracheal intubation was established in studies in pediatric patients aged 1 month to 12 years old. In these studies, patients had general anesthesia and mechanical ventilation.

In Study 6, a cisatracurium besylate dose of 0.1 mg/kg was evaluated in 16 pediatric patients (ages 2 years to 12 years) during opioid anesthesia. When administered during stable opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, maximum neuromuscular blockade was achieved in an average of 2.8 minutes (range: 1.8 to 6.7 minutes) with a clinically effective block for 28 minutes (range: 21 to 38 minutes).

In Study 7, a cisatracurium besylate dose of 0.15 mg/kg was evaluated in 50 pediatric patients (ages 1 month to 12 years) during opioid anesthesia. When administered during stable opioid/nitrous oxide/oxygen anesthesia, maximum neuromuscular blockade was achieved in an average of about 3 minutes (range: 1.5 to 8 minutes) with a clinically effective block for 36 minutes (range: 29 to 46 minutes) in 24 patients ages 2 to 12 years. In 27 infants (1 to 23 months), maximum neuromuscular block was achieved in about 2 minutes (range: 1.3 to 4.3 minutes) with a clinically effective block for about 43 minutes (range: 34 to 58 minutes) with this dose.

Study 7 also evaluated intubating conditions in 180 pediatric patients (ages 1 month to 12 years) after administration of cisatracurium besylate doses of 0.15 mg/kg following induction with either halothane (with halothane/nitrous oxide/oxygen maintenance) or thiopentone and fentanyl (with thiopentone/fentanyl nitrous oxide/oxygen maintenance). Table 13 displays the intubating conditions by type of anesthesia, and pediatric age group. Excellent or good intubating conditions were produced 120 seconds following 0.15 mg/kg of cisatracurium besylate in 88/90 (98%) of patients induced with halothane and in 85/90 (94%) of patients induced with thiopentone and fentanyl. There were no patients for whom intubation was not possible, but there were 7/120 patients aged 1 year to 12 years old for whom intubating conditions were described as poor.

Table 13. Intubating Conditions at 120 Seconds* in Pediatric Patients Ages 1 Month to 12 Years Old in Study 7

|

Cisatracurium Besylate 0.15 mg/kg 1-11 mo. |

Cisatracurium Besylate 0.15 mg/kg 1-4 years |

Cisatracurium Besylate 0.15 mg/kg 5-12 years |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

87% |

|

97% |

|

|

83% |

|

63% |

|

70% |

|

|

17% |

|

23% |

|

27% |

|

|

0% |

|

13% |

|

3% |

|

*Excellent: Easy passage of the tube without coughing. Vocal cords relaxed and abducted. Good: Passage of tube with slight coughing and/or bucking. Vocal cords relaxed and abducted.

|

||||||

14.3 Skeletal Muscle Relaxation in ICU Patients

Long-term infusion (up to 6 days) of cisatracurium besylate during mechanical ventilation in the ICU was evaluated in two studies.

Study 8 was a randomized, double-blind study using presence of a single twitch during train-of-four (TOF) monitoring to regulate dosage. Patients treated with cisatracurium besylate (n=19) recovered neuromuscular function (T4:T1 ratio ≥70%) following termination of infusion in approximately 55 minutes (range: 20 to 270).

In Study 9, cisatracurium besylate patients recovered neuromuscular function in approximately 50 minutes (range: 20 to 175; n=34).

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

Cisatracurium besylate injection, USP 10 mg cisatracurium per mL, is supplied as under:

|

NDC |

Container |

Size |

|

72572-067-10 |

20 mL Single-dose Vial |

Pack of 10's |

Intended only for use in the ICU.

Discard unused portion.

Storage

Cisatracurium besylate injection, USP should be refrigerated at 2° to 8°C (36° to 46°F) in the carton to preserve potency. Protect from light. DO NOT FREEZE. Upon removal of the unused vial from refrigeration to room temperature storage conditions (25°C/77°F), use cisatracurium besylate injection within 21 days, even if re-refrigerated.

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Hypersensitivity Reactions Including Anaphylaxis

Advise the caregiver and/or family that severe hypersensitivity reactions have occurred with cisatracurium besylate [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

Distributed by:

Civica, Inc.

Lehi, Utah 84043

Manufactured by:

Gland Pharma Limited

Telangana, India

1313000731-01