DESCRIPTION

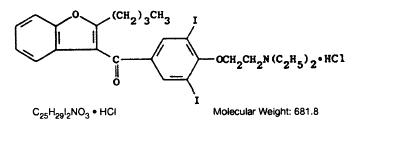

Amiodarone hydrochloride is a member of a new class of antiarrhythmic drugs with predominantly Class III (Vaughan Williams’ classification) effects. Amiodarone is a benzofuran derivative: 2-butyl-3-benzofuranyl 4-[2-(diethylamino)-ethoxy]-3,5-diiodophenyl ketone hydrochloride. It is not chemically related to any other available antiarrhythmic drug.

The structural formula is as follows:

Amiodarone hydrochloride is a white to cream-colored crystalline powder. It is slightly soluble in water, soluble in alcohol and freely soluble in chloroform. It contains 37.3% iodine by weight.

Each amiodarone hydrochloride tablet intended for oral administration contains 200 mg of amiodarone hydrochloride. In addition each tablet contains the following inactive ingredients: colloidal silicon dioxide, corn starch, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, povidone and sodium starch glycolate.

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Electrophysiology/Mechanisms of Action:

In animals, amiodarone is effective in the prevention or suppression of experimentally induced arrhythmias. The antiarrhythmic effect of amiodarone may be due to at least two major properties:

- a prolongation of the myocardial cell-action potential duration and refractory period and

- noncompetitive α- and β-adrenergic inhibition.

Amiodarone prolongs the duration of the action potential of all cardiac fibers while causing minimal reduction of dV/dt (maximal upstroke velocity of the action potential). The refractory period is prolonged in all cardiac tissues. Amiodarone increases the cardiac refractory period without influencing resting membrane potential, except in automatic cells where the slope of the prepotential is reduced, generally reducing automaticity. These electrophysiologic effects are reflected in a decreased sinus rate of 15 to 20%, increased PR and QT intervals of about 10%, the development of U-waves, and changes in T-wave contour. These changes should not require discontinuation of amiodarone as they are evidence of its pharmacological action, although amiodarone can cause marked sinus bradycardia or sinus arrest and heart block. On rare occasions, QT prolongation has been associated with worsening of arrhythmia (see WARNINGS).

Hemodynamics:

In animal studies and after intravenous administration in man, amiodarone relaxes vascular smooth muscle, reduces peripheral vascular resistance (afterload), and slightly increases cardiac index. After oral dosing, however, amiodarone produces no significant change in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), even in patients with depressed LVEF. After acute intravenous dosing in man, amiodarone may have a mild negative inotropic effect.

Pharmacokinetics:

Following oral administration in man, amiodarone is slowly and variably absorbed. The bioavailability of amiodarone is approximately 50%, but has varied between 35 and 65% in various studies. Maximum plasma concentrations are attained 3 to 7 hours after a single dose. Despite this, the onset of action may occur in 2 to 3 days, but more commonly takes 1 to 3 weeks, even with loading doses. Plasma concentrations with chronic dosing at 100 to 600 mg/day are approximately dose proportional, with a mean 0.5 mg/L increase for each 100 mg/day. These means, however, include considerable individual variability. Food increases the rate and extent of absorption of amiodarone. The effects of food upon the bioavailability of amiodarone have been studied in 30 healthy subjects who received a single 600 mg dose immediately after consuming a high-fat meal and following an overnight fast. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) and the peak plasma concentration (Cmax) of amiodarone increased by 2.3 (range 1.7 to 3.6) and 3.8 (range 2.7 to 4.4) times, respectively, in the presence of food. Food also increased the rate of absorption of amiodarone, decreasing the time to peak plasma concentration (Tmax) by 37%. The mean AUC and mean Cmax of desethylamiodarone increased by 55% (range 58 to 101%) and 32% (range 4 to 84%), respectively, but there was no change in the Tmax in the presence of food.

Amiodarone has a very large but variable volume of distribution, averaging about 60 L/kg, because of extensive accumulation in various sites, especially adipose tissue and highly perfused organs, such as the liver, lung, and spleen. One major metabolite of amiodarone, desethylamiodarone (DEA), has been identified in man; it accumulates to an even greater extent in almost all tissues. No data are available on the activity of DEA in humans, but in animals, it has significant electrophysiologic and antiarrhythmic effects generally similar to amiodarone itself. DEA’s precise role and contribution to the antiarrhythmic activity of oral amiodarone are not certain. The development of maximal ventricular Class III effects after oral amiodarone administration in humans correlates more closely with DEA accumulation over time than with amiodarone accumulation.

Amiodarone is metabolized to desethylamiodarone by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme group, specifically cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and CYP2C8. The CYP3A4 isoenzyme is present in both the liver and intestines.

Amiodarone is eliminated primarily by hepatic metabolism and biliary excretion and there is negligible excretion of amiodarone or DEA in urine. Neither amiodarone nor DEA is dialyzable.

In clinical studies of 2 to 7 days, clearance of amiodarone after intravenous administration in patients with VT and VF ranged between 220 and 440 mL/hr/kg. Age, sex, renal disease, and hepatic disease (cirrhosis) do not have marked effects on the disposition of amiodarone or DEA. Renal impairment does not influence the pharmacokinetics of amiodarone. After a single dose of intravenous amiodarone in cirrhotic patients, significantly lower Cmax and average concentration values are seen for DEA, but mean amiodarone levels are unchanged. Normal subjects over 65 years of age show lower clearances (about 100 mL/hr/kg) than younger subjects (about 150 mL/hr/kg) and an increase in t½ from about 20 to 47 days. In patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction, the pharmacokinetics of amiodarone are not significantly altered but the terminal disposition t½ of DEA is prolonged. Although no dosage adjustment for patients with renal, hepatic, or cardiac abnormalities has been defined during chronic treatment with amiodarone, close clinical monitoring is prudent for elderly patients and those with severe left ventricular dysfunction.

Following single dose administration in 12 healthy subjects, amiodarone exhibited multi-compartmental pharmacokinetics with a mean apparent plasma terminal elimination half-life of 58 days (range 15 to 142 days) for amiodarone and 36 days (range 14 to 75 days) for the active metabolite (DEA). In patients, following discontinuation of chronic oral therapy, amiodarone has been shown to have a biphasic elimination with an initial one-half reduction of plasma levels after 2.5 to 10 days. A much slower terminal plasma-elimination phase shows a half-life of the parent compound ranging from 26 to 107 days, with a mean of approximately 53 days and most patients in the 40- to 55-day range. In the absence of a loading-dose period, steady-state plasma concentrations, at constant oral dosing, would therefore be reached between 130 and 535 days, with an average of 265 days. For the metabolite, the mean plasma-elimination half-life was approximately 61 days. These data probably reflect an initial elimination of drug from well-perfused tissue (the 2.5- to 10-day half-life phase), followed by a terminal phase representing extremely slow elimination from poorly perfused tissue compartments such as fat.

The considerable intersubject variation in both phases of elimination, as well as uncertainty as to what compartment is critical to drug effect, requires attention to individual responses once arrhythmia control is achieved with loading doses because the correct maintenance dose is determined, in part, by the elimination rates. Daily maintenance doses of amiodarone should be based on individual patient requirements (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Amiodarone and its metabolite have a limited transplacental transfer of approximately 10 to 50%. The parent drug and its metabolite have been detected in breast milk.

Amiodarone is highly protein-bound (approximately 96%).

Although electrophysiologic effects, such as prolongation of QTc, can be seen within hours after a parenteral dose of amiodarone, effects on abnormal rhythms are not seen before 2 to 3 days and usually require 1 to 3 weeks, even when a loading dose is used. There may be a continued increase in effect for longer periods still. There is evidence that the time to effect is shorter when a loading-dose regimen is used.

Consistent with the slow rate of elimination, antiarrhythmic effects persist for weeks or months after amiodarone is discontinued, but the time of recurrence is variable and unpredictable. In general, when the drug is resumed after recurrence of the arrhythmia, control is established relatively rapidly compared to the initial response, presumably because tissue stores were not wholly depleted at the time of recurrence.

Pharmacodynamics:

There is no well-established relationship of plasma concentration to effectiveness, but it does appear that concentrations much below 1 mg/L are often ineffective and that levels above 2.5 mg/L are generally not needed. Within individuals dose reductions and ensuing decreased plasma concentrations can result in loss of arrhythmia control. Plasma-concentration measurements can be used to identify patients whose levels are unusually low, and who might benefit from a dose increase, or unusually high, and who might have dosage reduction in the hope of minimizing side effects. Some observations have suggested a plasma concentration, dose, or dose/duration relationship for side effects such as pulmonary fibrosis, liver-enzyme elevations, corneal deposits and facial pigmentation, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal and central nervous system effects.

Monitoring Effectiveness:

Predicting the effectiveness of any antiarrhythmic agent in long-term prevention of recurrent ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation is difficult and controversial, with highly qualified investigators recommending use of ambulatory monitoring, programmed electrical stimulation with various stimulation regimens, or a combination of these, to assess response. There is no present consensus on many aspects of how best to assess effectiveness, but there is a reasonable consensus on some aspects:

- If a patient with a history of cardiac arrest does not manifest a hemodynamically unstable arrhythmia during electrocardiographic monitoring prior to treatment, assessment of the effectiveness of amiodarone requires some provocative approach, either exercise or programmed electrical stimulation (PES).

- Whether provocation is also needed in patients who do manifest their life-threatening arrhythmia spontaneously is not settled, but there are reasons to consider PES or other provocation in such patients. In the fraction of patients whose PES-inducible arrhythmia can be made noninducible by amiodarone (a fraction that has varied widely in various series from less than 10% to almost 40%, perhaps due to different stimulation criteria), the prognosis has been almost uniformly excellent, with very low recurrence (ventricular tachycardia or sudden death) rates. More controversial is the meaning of continued inducibility. There has been an impression that continued inducibility in amiodarone patients may not foretell a poor prognosis but, in fact, many observers have found greater recurrence rates in patients who remain inducible than in those who do not. A number of criteria have been proposed, however, for identifying patients who remain inducible but who seem likely nonetheless to do well on amiodarone. These criteria include increased difficulty of induction (more stimuli or more rapid stimuli), which has been reported to predict a lower rate of recurrence, and ability to tolerate the induced ventricular tachycardia without severe symptoms, a finding that has been reported to correlate with better survival but not with lower recurrence rates. While these criteria require confirmation and further study in general, easier inducibility or poorer tolerance of the induced arrhythmia should suggest consideration of a need to revise treatment.

Several predictors of success not based on PES have also been suggested, including complete elimination of all nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on ambulatory monitoring and very low premature ventricular-beat rates (less than 1 VPB/1,000 normal beats).

While these issues remain unsettled for amiodarone, as for other agents, the prescriber of amiodarone should have access to (direct or through referral), and familiarity with, the full range of evaluatory procedures used in the care of patients with life-threatening arrhythmias.

It is difficult to describe the effectiveness rates of amiodarone, as these depend on the specific arrhythmia treated, the success criteria used, the underlying cardiac disease of the patient, the number of drugs tried before resorting to amiodarone, the duration of follow-up, the dose of amiodarone, the use of additional antiarrhythmic agents, and many other factors. As amiodarone has been studied principally in patients with refractory life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, in whom drug therapy must be selected on the basis of response and cannot be assigned arbitrarily, randomized comparisons with other agents or placebo have not been possible. Reports of series of treated patients with a history of cardiac arrest and mean follow-up of one year or more have given mortality (due to arrhythmia) rates that were highly variable, ranging from less than 5% to over 30%, with most series in the range of 10 to 15%. Overall arrhythmia-recurrence rates (fatal and nonfatal) also were highly variable (and, as noted above, depended on response to PES and other measures), and depend on whether patients who do not seem to respond initially are included. In most cases, considering only patients who seemed to respond well enough to be placed on long-term treatment, recurrence rates have ranged from 20 to 40% in series with a mean follow-up of a year or more.

INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Because of its life-threatening side effects and the substantial management difficulties associated with its use (see WARNINGS below), amiodarone is indicated only for the treatment of the following documented, life-threatening recurrent ventricular arrhythmias when these have not responded to documented adequate doses of other available antiarrhythmics or when alternative agents could not be tolerated.

- Recurrent ventricular fibrillation.

- Recurrent hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia.

As is the case for other antiarrhythmic agents, there is no evidence from controlled trials that the use of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets favorably affects survival.

Amiodarone should be used only by physicians familiar with and with access to (directly or through referral) the use of all available modalities for treating recurrent life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, and who have access to appropriate monitoring facilities, including in-hospital and ambulatory continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and electrophysiologic techniques. Because of the life-threatening nature of the arrhythmias treated, potential interactions with prior therapy, and potential exacerbation of the arrhythmia, initiation of therapy with amiodarone should be carried out in the hospital.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Amiodarone is contraindicated in patients with cardiogenic shock, severe sinus-node dysfunction, causing marked sinus bradycardia; second- or third-degree atrioventricular block; and when episodes of bradycardia have caused syncope (except when used in conjunction with a pacemaker).

Amiodarone is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or to any of its components, including iodine.

WARNINGS

Amiodarone is intended for use only in patients with the indicated life-threatening arrhythmias because its use is accompanied by substantial toxicity.

Amiodarone has several potentially fatal toxicities, the most important of which is pulmonary toxicity (hypersensitivity pneumonitis or interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis) that has resulted in clinically manifest disease at rates as high as 10 to 17% in some series of patients with ventricular arrhythmias given doses around 400 mg/day, and as abnormal diffusion capacity without symptoms in a much higher percentage of patients. Pulmonary toxicity has been fatal about 10% of the time. Liver injury is common with amiodarone, but is usually mild and evidenced only by abnormal liver enzymes. Overt liver disease can occur, however, and has been fatal in a few cases. Like other antiarrhythmics, amiodarone can exacerbate the arrhythmia, e.g., by making the arrhythmia less well tolerated or more difficult to reverse. This has occurred in 2 to 5% of patients in various series, and significant heart block or sinus bradycardia has been seen in 2 to 5%. All of these events should be manageable in the proper clinical setting in most cases. Although the frequency of such proarrhythmic events does not appear greater with amiodarone than with many other agents used in this population, the effects are prolonged when they occur.

Even in patients at high risk of arrhythmic death, in whom the toxicity of amiodarone is an acceptable risk, amiodarone poses major management problems that could be life-threatening in a population at risk of sudden death, so that every effort should be made to utilize alternative agents first.

The difficulty of using amiodarone effectively and safely itself poses a significant risk to patients. Patients with the indicated arrhythmias must be hospitalized while the loading dose of amiodarone is given, and a response generally requires at least one week, usually two or more. Because absorption and elimination are variable, maintenance-dose selection is difficult, and it is not unusual to require dosage decrease or discontinuation of treatment. In a retrospective survey of 192 patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias, 84 required dose reduction and 18 required at least temporary discontinuation because of adverse effects, and several series have reported 15 to 20% overall frequencies of discontinuation due to adverse reactions. The time at which a previously controlled life-threatening arrhythmia will recur after discontinuation or dose adjustment is unpredictable, ranging from weeks to months. The patient is obviously at great risk during this time and may need prolonged hospitalization. Attempts to substitute other antiarrhythmic agents when amiodarone must be stopped will be made difficult by the gradually, but unpredictably, changing amiodarone body burden. A similar problem exists when amiodarone is not effective; it still poses the risk of an interaction with whatever subsequent treatment is tried.

Mortality:

In the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST), a long-term, multi-centered, randomized, double-blind study in patients with asymptomatic non-life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias who had had myocardial infarctions more than six days but less than two years previously, an excessive mortality or non-fatal cardiac arrest rate was seen in patients treated with encainide or flecainide (56/730) compared with that seen in patients assigned to matched placebo-treated groups (22/725). The average duration of treatment with encainide or flecainide in this study was ten months.

Amiodarone therapy was evaluated in two multi-centered, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials involving 1202 (Canadian Amiodarone Myocardial Infarction Arrhythmia Trial; CAMIAT) and 1486 (European Myocardial Infarction Amiodarone Trial; EMIAT) post-MI patients followed for up to 2 years. Patients in CAMIAT qualified with ventricular arrhythmias, and those randomized to amiodarone received weight- and response-adjusted doses of 200 to 400 mg/day. Patients in EMIAT qualified with ejection fraction <40%, and those randomized to amiodarone received fixed doses of 200 mg/day. Both studies had weeks-long loading dose schedules. Intent-to-treat all-cause mortality results were as follows:

|

| Placebo

| Amiodarone

| Relative Risk

|

|||

|

| N

| Deaths

| N

| Deaths

|

| 95%CI

|

| EMIAT

| 743

| 102

| 743

| 103

| 0.99

| 0.76-1.31

|

| CAMIAT

| 596

| 68

| 606

| 57

| 0.88

| 0.58-1.16

|

These data are consistent with the results of a pooled analysis of smaller, controlled studies involving patients with structural heart disease (including myocardial infarction).

Pulmonary Toxicity:

There have been post-marketing reports of acute-onset (days to weeks) pulmonary injury in patients treated with oral amiodarone with or without initial I.V. therapy. Findings have included pulmonary infiltrates and/or X-ray, pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage, pleural effusion, bronchospasm, wheezing, fever, dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, and hypoxia. Some cases have progressed to respiratory failure and/or death. Post-marketing reports describe cases of pulmonary toxicity in patients treated with low doses of amiodarone; however, reports suggest that the use of lower loading and maintenance doses of amiodarone are associated with a decreased incidence of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity.

Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets may cause a clinical syndrome of cough and progressive dyspnea accompanied by functional, radiographic, gallium-scan, and pathological data consistent with pulmonary toxicity, the frequency of which varies from 2 to 7% in most published reports, but is as high as 10 to 17% in some reports. Therefore, when amiodarone therapy is initiated, a baseline chest X-ray and pulmonary-function tests, including diffusion capacity, should be performed. The patient should return for a history, physical exam, and chest X-ray every 3 to 6 months.

Pulmonary toxicity secondary to amiodarone seems to result from either indirect or direct toxicity as represented by hypersensitivity pneumonitis (including eosinophilic pneumonia) or interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis, respectively.

Patients with preexisting pulmonary disease have a poorer prognosis if pulmonary toxicity develops.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis usually appears earlier in the course of therapy, and rechallenging these patients with amiodarone results in a more rapid recurrence of greater severity.

Bronchoalveolar lavage is the procedure of choice to confirm this diagnosis, which can be made when a T suppressor/cytotoxic (CD8-positive) lymphocytosis is noted. Steroid therapy should be instituted and amiodarone therapy discontinued in these patients.

Interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis may result from the release of oxygen radicals and/or phospholipidosis and is characterized by findings of diffuse alveolar damage, interstitial pneumonitis or fibrosis in lung biopsy specimens. Phospholipidosis (foamy cells, foamy macrophages), due to inhibition of phospholipase, will be present in most cases of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity; however, these changes also are present in approximately 50% of all patients on amiodarone therapy. These cells should be used as markers of therapy, but not as evidence of toxicity. A diagnosis of amiodarone-induced interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis should lead, at a minimum, to dose reduction or, preferably, to withdrawal of the amiodarone to establish reversibility, especially if other acceptable antiarrhythmic therapies are available. Where these measures have been instituted, a reduction in symptoms of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity was usually noted within the first week, and a clinical improvement was greatest in the first two to three weeks. Chest X-ray changes usually resolve within two to four months. According to some experts, steroids may prove beneficial. Prednisone in doses of 40 to 60 mg/day or equivalent doses of other steroids have been given and tapered over the course of several weeks depending upon the condition of the patient. In some cases rechallenge with amiodarone at a lower dose has not resulted in return of toxicity.

In a patient receiving amiodarone, any new respiratory symptoms should suggest the possibility of pulmonary toxicity, and the history, physical exam, chest X-ray, and pulmonary-function tests (with diffusion capacity) should be repeated and evaluated. A 15% decrease in diffusion capacity has a high sensitivity but only a moderate specificity for pulmonary toxicity; as the decrease in diffusion capacity approaches 30%, the sensitivity decreases but the specificity increases. A gallium-scan also may be performed as part of the diagnostic workup.

Fatalities, secondary to pulmonary toxicity, have occurred in approximately 10% of cases. However, in patients with life-threatening arrhythmias, discontinuation of amiodarone therapy due to suspected drug-induced pulmonary toxicity should be undertaken with caution, as the most common cause of death in these patients is sudden cardiac death. Therefore, every effort should be made to rule out other causes of respiratory impairment (i.e., congestive heart failure with Swan-Ganz catheterization if necessary, respiratory infection, pulmonary embolism, malignancy, etc.) before discontinuing amiodarone in these patients. In addition, bronchoalveolar lavage, transbronchial lung biopsy and/or open lung biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis, especially in those cases where no acceptable alternative therapy is available.

If a diagnosis of amiodarone-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis is made, amiodarone should be discontinued, and treatment with steroids should be instituted. If a diagnosis of amiodarone-induced interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis is made, steroid therapy should be instituted and, preferably, amiodarone discontinued or, at a minimum, reduced in dosage. Some cases of amiodarone-induced interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis may resolve following a reduction in amiodarone dosage in conjunction with the administration of steroids. In some patients, rechallenge at a lower dose has not resulted in return of interstitial/alveolar pneumonitis; however, in some patients (perhaps because of severe alveolar damage) the pulmonary lesions have not been reversible.

Worsened Arrhythmia:

Amiodarone, like other antiarrhythmics, can cause serious exacerbation of the presenting arrhythmia, a risk that may be enhanced by the presence of concomitant antiarrhythmics. Exacerbation has been reported in about 2 to 5% in most series, and has included new ventricular fibrillation, incessant ventricular tachycardia, increased resistance to cardioversion, and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia associated with QTc prolongation (torsades de pointes [TdP]). In addition, amiodarone has caused symptomatic bradycardia or sinus arrest with suppression of escape foci in 2 to 4% of patients.

Fluoroquinolones, macrolide antibiotics, and azoles are known to cause QTc prolongation. There have been reports of QTc prolongation, with or without TdP, in patients taking amiodarone when fluoroquinolones, macrolide antibiotics, or azoles were administered concomitantly (see Drug Interactions, Other reported interactions with amiodarone).

The need to co-administer amiodarone with any other drug known to prolong the QTc interval must be based on a careful assessment of the potential risks and benefits of doing so for each patient.

A careful assessment of the potential risks and benefits of administering amiodarone must be made in patients with thyroid dysfunction due to the possibility of arrhythmia breakthrough or exacerbation of arrhythmia in these patients.

Implantable Cardiac Devices

In patients with implanted defibrillators or pacemakers, chronic administration of antiarrhythmic drugs may affect pacing or defibrillating thresholds. Therefore, at the inception of and during amiodarone treatment, pacing and defibrillation thresholds should be assessed.

Thyrotoxicosis:

Amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism may result in thyrotoxicosis and/or the possibility of arrhythmia breakthrough or aggravation. There have been reports of death associated with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. IF ANY NEW SIGNS OF ARRHYTHMIA APPEAR, THE POSSIBILITY OF HYPERTHYROIDISM SHOULD BE CONSIDERED (see PRECAUTIONS, Thyroid Abnormalities).

Liver Injury:

Elevations of hepatic enzyme levels are seen frequently in patients exposed to amiodarone and in most cases are asymptomatic. If the increase exceeds three times normal, or doubles in a patient with an elevated baseline, discontinuation of amiodarone or dosage reduction should be considered. In a few cases in which biopsy has been done, the histology has resembled that of alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis. Hepatic failure has been a rare cause of death in patients treated with amiodarone.

Loss of Vision:

Cases of optic neuropathy and/or optic neuritis, usually resulting in visual impairment, have been reported in patients treated with amiodarone. In some cases, visual impairment has progressed to permanent blindness. Optic neuropathy and/or neuritis may occur at any time following initiation of therapy. A causal relationship to the drug has not been clearly established. If symptoms of visual impairment appear, such as changes in visual acuity and decreases in peripheral vision, prompt ophthalmic examination is recommended. Appearance of optic neuropathy and/or neuritis calls for re-evaluation of amiodarone therapy. The risks and complications of antiarrhythmic therapy with amiodarone must be weighed against its benefits in patients whose lives are threatened by cardiac arrhythmias. Regular ophthalmic examination, including funduscopy and slit-lamp examination, is recommended during administration of amiodarone (see ADVERSE REACTIONS).

Neonatal Hypo- or Hyperthyroidism:

Amiodarone can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. Although amiodarone use during pregnancy is uncommon, there have been a small number of published reports of congenital goiter/hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. If amiodarone hydrochloride tablets are used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking amiodarone, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus.

In general, amiodarone hydrochloride tablets should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit to the mother justifies the unknown risk to the fetus.

In pregnant rats and rabbits, amiodarone hydrochloride in doses of 25 mg/kg/day (approximately 0.4 and 0.9 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human maintenance dose*) had no adverse effects on the fetus. In the rabbit, 75 mg/kg/day (approximately 2.7 times the maximum recommended human maintenance dose*) caused abortions in greater than 90% of the animals. In the rat, doses of 50 mg/kg/day or more were associated with slight displacement of the testes and an increased incidence of incomplete ossification of some skull and digital bones; at 100 mg/kg/day or more, fetal body weights were reduced; at 200 mg/kg/day, there was an increased incidence of fetal resorption. (These doses in the rat are approximately 0.8, 1.6 and 3.2 times the maximum recommended human maintenance dose*). Adverse effects on fetal growth and survival also were noted in one of two strains of mice at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day (approximately 0.04 times the maximum recommended human maintenance dose*).

* 600 mg in a 50 kg patient (doses compared on a body surface area basis)

PRECAUTIONS

Optic Neuropathy and/or Neuritis:

Cases of optic neuropathy and optic neuritis have been reported (see WARNINGS).

Corneal Microdeposits:

Corneal microdeposits appear in the majority of adults treated with amiodarone. They are usually discernible only by slit-lamp examination, but give rise to symptoms such as visual halos or blurred vision in as many as 10% of patients. Corneal microdeposits are reversible upon reduction of dose or termination of treatment. Asymptomatic microdeposits alone are not a reason to reduce dose or discontinue treatment (see ADVERSE REACTIONS).

Neurologic:

Chronic administration of oral amiodarone in rare instances may lead to the development of peripheral neuropathy that may resolve when amiodarone is discontinued, but this resolution has been slow and incomplete.

Photosensitivity:

Amiodarone has induced photosensitization in about 10% of patients; some protection may be afforded by the use of sun-barrier creams or protective clothing. During long-term treatment, a blue-gray discoloration of the exposed skin may occur. The risk may be increased in patients of fair complexion or those with excessive sun exposure, and may be related to cumulative dose and duration of therapy.

Thyroid Abnormalities:

Amiodarone inhibits peripheral conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) and may cause increased thyroxine levels, decreased T3 levels, and increased levels of inactive reverse T3 (rT3) in clinically euthyroid patients. It is also a potential source of large amounts of inorganic iodine. Because of its release of inorganic iodine, or perhaps for other reasons, amiodarone can cause either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Thyroid function should be monitored prior to treatment and periodically thereafter, particularly in elderly patients, and in any patient with a history of thyroid nodules, goiter, or other thyroid dysfunction. Because of the slow elimination of amiodarone and its metabolites, high plasma iodide levels, altered thyroid function, and abnormal thyroid-function tests may persist for several weeks or even months following amiodarone withdrawal.

Hypothyroidism has been reported in 2 to 4% of patients in most series, but in 8 to 10% in some series. This condition may be identified by relevant clinical symptoms and particularly by elevated serum TSH levels. In some clinically hypothyroid amiodarone-treated patients, free thyroxine index values may be normal. Hypothyroidism is best managed by amiodarone dose reduction and/or thyroid hormone supplement. However, therapy must be individualized, and it may be necessary to discontinue amiodarone hydrochloride tablets in some patients.

Hyperthyroidism occurs in about 2% of patients receiving amiodarone, but the incidence may be higher among patients with prior inadequate dietary iodine intake. Amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism usually poses a greater hazard to the patient than hypothyroidism because of the possibility of thyrotoxicosis and/or arrhythmia breakthrough or aggravation, all of which may result in death. There have been reports of death associated with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. IF ANY NEW SIGNS OF ARRHYTHMIA APPEAR, THE POSSIBILITY OF HYPERTHYROIDISM SHOULD BE CONSIDERED.

Hyperthyroidism is best identified by relevant clinical symptoms and signs, accompanied usually by abnormally elevated levels of serum T3 RIA, and further elevations of serum T4, and a subnormal serum TSH level (using a sufficiently sensitive TSH assay). The finding of a flat TSH response to TRH is confirmatory of hyperthyroidism and may be sought in equivocal cases. Since arrhythmia breakthroughs may accompany amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism, aggressive medical treatment is indicated, including, if possible, dose reduction or withdrawal of amiodarone.

The institution of antithyroid drugs, β-adrenergic blockers and/or temporary corticosteroid therapy may be necessary. The action of antithyroid drugs may be especially delayed in amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis because of substantial quantities of preformed thyroid hormones stored in the gland. Radioactive iodine therapy is contraindicated because of the low radioiodine uptake associated with amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism. Amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism may be followed by a transient period of hypothyroidism (see WARNINGS, Thyrotoxicosis).

When aggressive treatment of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis has failed or amiodarone cannot be discontinued because it is the only drug effective against the resistant arrhythmia, surgical management may be an option. Experience with thyroidectomy as a treatment for amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis is limited, and this form of therapy could induce thyroid storm. Therefore, surgical and anesthetic management require careful planning.

There have been postmarketing reports of thyroid nodules/thyroid cancer in patients treated with amiodarone. In some instances hyperthyroidism was also present (see WARNINGS and ADVERSE REACTIONS).

Volatile Anesthetic Agents:

Close perioperative monitoring is recommended in patients undergoing general anesthesia who are on amiodarone therapy as they may be more sensitive to the myocardial depressant and conduction effects of halogenated inhalational anesthetics.

Hypotension Postbypass:

Rare occurrences of hypotension upon discontinuation of cardiopulmonary bypass during open-heart surgery in patients receiving amiodarone have been reported. The relationship of this event to amiodarone therapy is unknown.

Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS):

Postoperatively, occurrences of ARDS have been reported in patients receiving amiodarone therapy who have undergone either cardiac or noncardiac surgery. Although patients usually respond well to vigorous respiratory therapy, in rare instances the outcome has been fatal. Until further studies have been performed, it is recommended that FiO2 and the determinants of oxygen delivery to the tissues (e.g., SaO2, PaO2) be closely monitored in patients on amiodarone.

Corneal Refractive Laser Surgery:

Patients should be advised that most manufacturers of corneal refractive laser surgery devices contraindicate that procedure in patients taking amiodarone.

Information for Patients

Patients should be instructed to read the accompanying Medication Guide each time they refill their prescription. The complete text of the Medication Guide is reprinted at the end of this document.

Laboratory Tests:

Elevations in liver enzymes (SGOT and SGPT) can occur. Liver enzymes in patients on relatively high maintenance doses should be monitored on a regular basis. Persistent significant elevations in the liver enzymes or hepatomegaly should alert the physician to consider reducing the maintenance dose of amiodarone or discontinuing therapy.

Amiodarone alters the results of thyroid-function tests, causing an increase in serum T4 and serum reverse T3, and a decline in serum T3 levels. Despite these biochemical changes, most patients remain clinically euthyroid.

Drug Interactions:

Amiodarone is metabolized to desethylamiodarone by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme group, specifically cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and CYP2C8. The CYP3A4 isoenzyme is present in both the liver and intestines (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, Pharmacokinetics). Amiodarone is an inhabitor of CYP3A4 and p-glycoprotein. Therefore, amiodarone has the potential for interactions with drugs or substances that may be substrates, inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4 and substrates of p-glycoprotein. While only a limited number of in vivo drug-drug interactions with amiodarone have been reported, the potential for other interactions should be anticipated. This is especially important for drugs associated with serious toxicity, such as other antiarrhythmics. If such drugs are needed, their dose should be reassessed and, where appropriate, plasma concentration measured. In view of the long and variable half-life of amiodarone, potential for drug interactions exists, not only with concomitant medication, but also with drugs administered after discontinuation of amiodarone.

Since amiodarone is a substrate for CYP3A4 and CYP2C8, drugs/substances that inhibit CYP3A4 may decrease the metabolism and increase serum concentrations of amiodarone. Reported examples include the following:

Protease inhibitors:

Protease inhibitors are known to inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees. A case report of one patient taking amiodarone 200 mg and indinavir 800 mg three times a day resulted in increases in amiodarone concentrations from 0.9 mg/L to 1.3 mg/L. DEA concentrations were not affected. There was no evidence of toxicity. Monitoring for amiodarone toxicity and serial measurement of amiodarone serum concentration during concomitant protease inhibitor therapy should be considered.

Histamine H1 antagonists:

Loratadine, a non-sedating antihistaminic, is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4. QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes have been reported with the co-administration of loratadine and amiodarone.

Histamine H2 antagonists:

Cimetidine inhibits CYP3A4 and can increase serum amiodarone levels.

Antidepressants:

Trazodone, an antidepressant, is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4. QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes have been reported with the co-administration of trazodone and amiodarone.

Other substances:

Grapefruit juice given to healthy volunteers increased amiodarone AUC by 50% and Cmax by 84%, and decreased DEA to unquantifiable concentrations. Grapefruit juice inhibits CYP3A4 mediated metabolism of oral amiodarone in the intestinal mucosa, resulting in increased plasma levels of amiodarone; therefore, grapefruit juice should not be taken during treatment with oral amiodarone. This information should be considered when changing from intravenous amiodarone to oral amiodarone (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

Amiodarone inhibits p-glycoprotein and certain CYP450 enzymes, including CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4. This inhibition can result in unexpectedly high plasma levels of other drugs which are metabolized by those CYP450 enzymes or are substrates of p-glycoprotein. Reported examples of this interaction include the following:

Immunosuppressives:

Cyclosporine (CYP3A4 substrate) administered in combination with oral amiodarone has been reported to produce persistently elevated plasma concentrations of cyclosporine resulting in elevated creatinine, despite reduction in dose of cyclosporine.

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors:

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors that are CYP3A4 substrates (including simvastatin and atorvastatin) in combination with amiodarone have been associated with reports of myopathy/rhabdomyolysis.

When co-administered with amiodarone, lower starting and maintenance doses of these agents should be considered.

Cardiac glycosides:

In patients receiving digoxin therapy, administration of oral amiodarone regularly results in an increase in the serum digoxin concentration that may reach toxic levels with resultant clinical toxicity. Amiodarone taken concomitantly with digoxin increases the serum digoxin concentration by 70% after one day. On initiation of oral amiodarone, the need for digitalis therapy should be reviewed and the dose reduced by approximately 50% or discontinued. If digitalis treatment is continued, serum levels should be closely monitored and patients observed for clinical evidence of toxicity. These precautions probably should apply to digitoxin administration as well.

Antiarrhythmics:

Other antiarrhythmic drugs, such as quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide, and phenytoin, have been used concurrently with oral amiodarone.

There have been case reports of increased steady-state levels of quinidine, procainamide, and phenytoin during concomitant therapy with amiodarone. Phenytoin decreases serum amiodarone levels. Amiodarone taken concomitantly with quinidine increases quinidine serum concentration by 33% after two days. Amiodarone taken concomitantly with procainamide for less than seven days increases plasma concentrations of procainamide and n-acetyl procainamide by 55% and 33%, respectively. Quinidine and procainamide doses should be reduced by one-third when either is administered with amiodarone. Plasma levels of flecainide have been reported to increase in the presence of oral amiodarone; because of this, the dosage of flecainide should be adjusted when these drugs are administered concomitantly. In general, any added antiarrhythmic drug should be initiated at a lower than usual dose with careful monitoring.

Combination of amiodarone with other antiarrhythmic therapy should be reserved for patients with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias who are incompletely responsive to a single agent or incompletely responsive to amiodarone. During transfer to amiodarone the dose levels of previously administered agents should be reduced by 30 to 50% several days after the addition of amiodarone, when arrhythmia suppression should be beginning. The continued need for the other antiarrhythmic agent should be reviewed after the effects of amiodarone have been established, and discontinuation ordinarily should be attempted. If the treatment is continued, these patients should be particularly carefully monitored for adverse effects, especially conduction disturbances and exacerbation of tachyarrhythmias, as amiodarone is continued. In amiodarone-treated patients who require additional antiarrhythmic therapy, the initial dose of such agents should be approximately half of the usual recommended dose.

Antihypertensives:

Amiodarone should be used with caution in patients receiving β-receptor blocking agents (e.g., propranolol, a CYP3A4 inhibitor) or calcium channel antagonists (e.g., verapamil, a CYP3A4 substrate, and diltiazem, a CYP3A4 inhibitor) because of the possible potentiation of bradycardia, sinus arrest, and AV block; if necessary, amiodarone can continue to be used after insertion of a pacemaker in patients with severe bradycardia or sinus arrest.

Anticoagulants:

Potentiation of warfarin-type (CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 substrate) anticoagulant response is almost always seen in patients receiving amiodarone and can result in serious or fatal bleeding. Since the concomitant administration of warfarin with amiodarone increases the prothrombin time by 100% after 3 to 4 days, the dose of the anticoagulant should be reduced by one-third to one-half, and prothrombin times should be monitored closely.

Clopidogrel, an inactive thienopyridine prodrug, is metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4 to an active metabolite. A potential interaction between clopidogrel and amiodarone resulting in ineffective inhibition of platelet aggregation has been reported.

Some drugs/substances are known to accelerate the metabolism of amiodarone by stimulating the synthesis of CYP3A4 (enzyme induction). This may lead to low amiodarone serum levels and potential decrease in efficacy. Reported examples of this interaction include the following:

Antibiotics:

Rifampin is a potent inducer of CYP3A4. Administration of rifampin concomitantly with oral amiodarone has been shown to result in decreases in serum concentrations of amiodarone and desethylamiodarone.

Other substances, including herbal preparations:

St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum) induces CYP3A4. Since amiodarone is a substrate for CYP3A4, there is the potential that the use of St. John’s Wort in patients receiving amiodarone could result in reduced amiodarone levels.

Other reported interactions with amiodarone:

Fentanyl (CYP3A4 substrate) in combination with amiodarone may cause hypotension, bradycardia, and decreased cardiac output.

Sinus bradycardia has been reported with oral amiodarone in combination with lidocaine (CYP3A4 substrate) given for local anesthesia. Seizure, associated with increased lidocaine concentrations, has been reported with concomitant administration of intravenous amiodarone.

Dextromethorphan is a substrate for both CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Amiodarone inhibits CYP2D6.

Cholestyramine increases enterohepatic elimination of amiodarone and may reduce its serum levels and t½.

Disopyramide increases QT prolongation which could cause arrhythmia.

Fluoroquinolones, macrolide antibiotics, and azoles are known to cause QTc prolongation. There have been reports of QTc prolongation, with or without TdP, in patients taking amiodarone when fluoroquinolones, macrolide antibiotics, or azoles were administered concomitantly (See WARNINGS, Worsened Arrhythmia).

Hemodynamic and electrophysiologic interactions have also been observed after concomitant administration with propranolol, diltiazem, and verapamil.

Volatile Anesthetic Agents:

See PRECAUTIONS, Surgery, Volatile Anesthetic Agents.

In addition to the interactions noted above, chronic (>2 weeks) oral amiodarone administration impairs metabolism of phenytoin, dextromethorphan, and methotrexate.

Electrolyte Disturbances:

Since antiarrhythmic drugs may be ineffective or may be arrhythmogenic in patients with hypokalemia, any potassium or magnesium deficiency should be corrected before instituting and during amiodarone therapy. Use caution when coadministering amiodarone with drugs which may induce hypokalemia and/or hypomagnesemia.

Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility:

Amiodarone hydrochloride was associated with a statistically significant, dose-related increase in the incidence of thyroid tumors (follicular adenoma and/or carcinoma) in rats. The incidence of thyroid tumors was greater than control even at the lowest dose level tested, i.e., 5 mg/kg/day (approximately 0.08 times the maximum recommended human maintenance dose*).

Mutagenicity studies (Ames, micronucleus, and lysogenic tests) with amiodarone were negative.

In a study in which amiodarone hydrochloride was administered to male and female rats, beginning 9 weeks prior to mating, reduced fertility was observed at a dose level of 90 mg/kg/day (approximately 1.4 times the maximum recommended human maintenance dose*).

*600 mg in a 50 kg patient (dose compared on a body surface area basis)

Labor and Delivery:

It is not known whether the use of amiodarone during labor or delivery has any immediate or delayed adverse effects. Preclinical studies in rodents have not shown any effect of amiodarone on the duration of gestation or on parturition.

Nursing Mothers:

Amiodarone and one of its major metabolites, desethylamiodarone (DEA), are excreted in human milk, suggesting that breast-feeding could expose the nursing infant to a significant dose of the drug. Nursing offspring of lactating rats administered amiodarone have been shown to be less viable and have reduced body-weight gains. Therefore, when amiodarone therapy is indicated, the mother should be advised to discontinue nursing.

Pediatric Use:

The safety and effectiveness of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets in pediatric patients have not been established.

Geriatric Use:

Clinical studies of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets did not include sufficient numbers of subjects aged 65 and over to determine whether they respond differently from younger subjects. Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

Adverse reactions have been very common in virtually all series of patients treated with amiodarone for ventricular arrhythmias with relatively large doses of drug (400 mg/day and above), occurring in about three-fourths of all patients and causing discontinuation in 7 to 18%. The most serious reactions are pulmonary toxicity, exacerbation of arrhythmia, and rare serious liver injury (see WARNINGS), but other adverse effects constitute important problems. They are often reversible with dose reduction or cessation of amiodarone treatment. Most of the adverse effects appear to become more frequent with continued treatment beyond six months, although rates appear to remain relatively constant beyond one year. The time and dose relationships of adverse effects are under continued study.

Neurologic problems are extremely common, occurring in 20 to 40% of patients and including malaise and fatigue, tremor and involuntary movements, poor coordination and gait, and peripheral neuropathy; they are rarely a reason to stop therapy and may respond to dose reductions or discontinuation (see PRECAUTIONS). There have been spontaneous reports of demyelinating polyneuropathy.

Gastrointestinal complaints, most commonly nausea, vomiting, constipation, and anorexia, occur in about 25% of patients but rarely require discontinuation of drug. These commonly occur during high-dose administration (i.e., loading dose) and usually respond to dose reduction or divided doses.

Ophthalmic abnormalities including optic neuropathy and/or optic neuritis, in some cases progressing to permanent blindness, papilledema, corneal degeneration, photosensitivity, eye discomfort, scotoma, lens opacities, and macular degeneration have been reported (see WARNINGS).

Asymptomatic corneal microdeposits are present in virtually all adult patients who have been on drug for more than 6 months. Some patients develop eye symptoms of halos, photophobia, and dry eyes. Vision is rarely affected and drug discontinuation is rarely needed.

Dermatological adverse reactions occur in about 15% of patients, with photosensitivity being most common (about 10%). Sunscreen and protection from sun exposure may be helpful, and drug discontinuation is not usually necessary. Prolonged exposure to amiodarone occasionally results in a blue-gray pigmentation. This is slowly and occasionally incompletely reversible on discontinuation of drug but is of cosmetic importance only.

Cardiovascular adverse reactions, other than exacerbation of the arrhythmias, include the uncommon occurrence of congestive heart failure (3%) and bradycardia. Bradycardia usually responds to dosage reduction but may require a pacemaker for control. CHF rarely requires drug discontinuation. Cardiac conduction abnormalities occur infrequently and are reversible on discontinuation of drug.

The following side-effect rates are based on a retrospective study of 241 patients treated for 2 to 1,515 days (mean 441.3 days).

The following side effects were each reported in 10 to 33% of patients:

Gastrointestinal: Nausea and vomiting.

The following side effects were each reported in 4 to 9% of patients:

Dermatologic: Solar dermatitis/photosensitivity.

Neurologic: Malaise and fatigue, tremor/abnormal involuntary movements, lack of coordination, abnormal gait/ataxia, dizziness, paresthesias.

Gastrointestinal: Constipation, anorexia.

Ophthalmologic: Visual disturbances.

Hepatic: Abnormal liver-function tests.

Respiratory: Pulmonary inflammation or fibrosis.

The following side effects were each reported in 1 to 3% of patients:

Thyroid: Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism.

Neurologic: Decreased libido, insomnia, headache, sleep disturbances.

Cardiovascular: Congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, SA node dysfunction.

Gastrointestinal: Abdominal pain.

Hepatic: Nonspecific hepatic disorders.

Other: Flushing, abnormal taste and smell, edema, abnormal salivation, coagulation abnormalities.

The following side effects were each reported in less than 1% of patients:

Blue skin discoloration, rash, spontaneous ecchymosis, alopecia, hypotension, and cardiac conduction abnormalities.

In surveys of almost 5,000 patients treated in open U.S. studies and in published reports of treatment with amiodarone, the adverse reactions most frequently requiring discontinuation of amiodarone included pulmonary infiltrates or fibrosis, paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and elevation of liver enzymes. Other symptoms causing discontinuations less often included visual disturbances, solar dermatitis, blue skin discoloration, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism.

Postmarketing Reports:

In postmarketing surveillance, hypotension (sometimes fatal), sinus arrest, anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction (including shock), angioedema, urticaria, eosinophilic pneumonia, hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis, cirrhosis, pancreatitis, renal impairment, renal insufficiency, acute renal failure, bronchospasm, possibly fatal respiratory disorders (including distress, failure, arrest, and ARDS), bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (possibly fatal), fever, dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, wheezing, hypoxia, pulmonary infiltrates and/or mass, pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage, pleural effusion, pleuritis, pseudotumor cerebri, parkinsonian symptoms such as akinesia and bradykinesia (sometimes reversible with discontinuation of therapy), syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), thyroid nodules/thyroid cancer, toxic epidermal necrolysis (sometimes fatal), erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, exfoliative dermatitis, eczema, skin cancer, vasculitis, pruritus, hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, pancytopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, agranulocytosis, granuloma, myopathy, muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis, demyelinating polyneuropathy, hallucination, confusional state, disorientation, delirium, epididymitis, and impotence, also have been reported with amiodarone therapy.

OVERDOSAGE

There have been cases, some fatal, of amiodarone overdose.

In addition to general supportive measures, the patient’s cardiac rhythm and blood pressure should be monitored, and if bradycardia ensues, a β-adrenergic agonist or a pacemaker may be used. Hypotension with inadequate tissue perfusion should be treated with positive inotropic and/or vasopressor agents. Neither amiodarone nor its metabolite is dialyzable.

The acute oral LD50 of amiodarone hydrochloride in mice and rats is greater than 3,000 mg/kg.

DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

BECAUSE OF THE UNIQUE PHARMACOKINETIC PROPERTIES, DIFFICULT DOSING SCHEDULE, AND SEVERITY OF THE SIDE EFFECTS IF PATIENTS ARE IMPROPERLY MONITORED, AMIODARONE SHOULD BE ADMINISTERED ONLY BY PHYSICIANS WHO ARE EXPERIENCED IN THE TREATMENT OF LIFE-THREATENING ARRHYTHMIAS WHO ARE THOROUGHLY FAMILIAR WITH THE RISKS AND BENEFITS OF AMIODARONE THERAPY, AND WHO HAVE ACCESS TO LABORATORY FACILITIES CAPABLE OF ADEQUATELY MONITORING THE EFFECTIVENESS AND SIDE EFFECTS OF TREATMENT.

In order to insure that an antiarrhythmic effect will be observed without waiting several months, loading doses are required. A uniform, optimal dosage schedule for administration of amiodarone has not been determined. Because of the food effect on absorption, amiodarone should be administered consistently with regard to meals (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). Individual patient titration is suggested according to the following guidelines:

For life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, such as ventricular fibrillation or hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia:

Close monitoring of the patients is indicated during the loading phase, particularly until risk of recurrent ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation has abated. Because of the serious nature of the arrhythmia and the lack of predictable time course of effect, loading should be performed in a hospital setting. Loading doses of 800 to 1,600 mg/day are required for 1 to 3 weeks (occasionally longer) until initial therapeutic response occurs. (Administration of amiodarone in divided doses with meals is suggested for total daily doses of 1,000 mg or higher, or when gastrointestinal intolerance occurs.) If side effects become excessive, the dose should be reduced. Elimination of recurrence of ventricular fibrillation and tachycardia usually occurs within 1 to 3 weeks, along with reduction in complex and total ventricular ectopic beats.

Since grapefruit juice is known to inhibit CYP3A4-mediated metabolism of oral amiodarone in the intestinal mucosa, resulting in increased plasma levels of amiodarone, grapefruit juice should not be taken during treatment with oral amiodarone (see PRECAUTIONS, Drug Interactions).

Upon starting amiodarone therapy, an attempt should be made to gradually discontinue prior antiarrhythmic drugs (see section on Drug Interactions). When adequate arrhythmia control is achieved, or if side effects become prominent, amiodarone dose should be reduced to 600 to 800 mg/day for one month and then to the maintenance dose, usually 400 mg/day (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Monitoring Effectiveness). Some patients may require larger maintenance doses, up to 600 mg/day, and some can be controlled on lower doses. Amiodarone may be administered as a single daily dose, or in patients with severe gastrointestinal intolerance, as a b.i.d. dose. In each patient, the chronic maintenance dose should be determined according to antiarrhythmic effect as assessed by symptoms, Holter recordings, and/or programmed electrical stimulation and by patient tolerance. Plasma concentrations may be helpful in evaluating nonresponsiveness or unexpectedly severe toxicity (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY).

The lowest effective dose should be used to prevent the occurrence of side effects. In all instances, the physician must be guided by the severity of the individual patient’s arrhythmia and response to therapy.

When dosage adjustments are necessary, the patient should be closely monitored for an extended period of time because of the long and variable half-life of amiodarone and the difficulty in predicting the time required to attain a new steady-state level of drug. Dosage suggestions are summarized below:

|

| Loading Dose (Daily)

| Adjustment and Maintenance Dose (Daily)

|

|

| Ventricular Arrhythmias | 1 to 3 weeks | ~1 month | usual maintenance |

|

| 800 to 1,600 mg | 600 to 800 mg | 400 mg |

HOW SUPPLIED

Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets, 200 mg are white to off-white, round-shaped, flat beveled-edge, uncoated tablets with bisect on one side and other side is plain; one side of bisect is debossed with ‘ZE’ and other side is debossed with ‘65’ and are supplied as follows:

| Bottle of 30 | NDC 54868-4618-1 |

| Bottles of 60 | NDC 54868-4618-0 |

| Bottles of 90 | NDC 54868-4618-3 |

| Bottles of 100 | NDC 54868-4618-2 |

STORAGE AND HANDLING

Store at 20° to 25°C (68° to 77°F) [See USP Controlled Room Temperature]. Protect from light.

Dispense in a tight, light-resistant container.

SPL MEDGUIDE

Read the Medication Guide that comes with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets before you start taking them and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This Medication Guide does not take the place of talking with your doctor about your medical condition or your treatment.

What is the most important information I should know about Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause serious side effects that can lead to death including:

- lung damage

- liver damage

- worse heartbeat problems

- thyroid problems

Call your doctor or get medical help right away if you have any symptoms such as the following:

- shortness of breath, wheezing, or any other trouble breathing; coughing, chest pain, or spitting up of blood

- nausea or vomiting; passing brown or dark-colored urine; feel more tired than usual; your skin and whites of your eyes get yellow; or have stomach pain

- heart pounding, skipping a beat, beating very fast or very slowly; feel light-headed or faint

- weakness, weight loss or weight gain, heat or cold intolerance, hair thinning, sweating, changes in your menses, swelling of your neck (goiter), nervousness, irritability, restlessness, decreased concentration, depression in the elderly, or tremor.

Because of these possible side effects, amiodarone hydrochloride tablets should only be used in adults with life-threatening heartbeat problems called ventricular arrhythmias, for which other treatments did not work or were not tolerated.

Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause other serious side effects. See "What are the possible or reasonably likely side effects of Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?" for more information.

If you get serious side effects during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets you may need to stop amiodarone hydrochloride tablets, have your dose changed, or get medical treatment. Talk with your doctor before you stop taking amiodarone hydrochloride tablets.

You may still have side effects after stopping amiodarone hydrochloride tablets because the medicine stays in your body months after treatment is stopped.

Tell all your healthcare providers that you take or took amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. This information is very important for other medical treatments or surgeries you may have.

What are Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

Amiodarone is a medicine used in adults to treat life-threatening heartbeat problems called ventricular arrhythmias, for which other treatment did not work or was not tolerated. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets have not been shown to help people with life-threatening heartbeat problems live longer. Treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets should be started in a hospital to monitor your condition. You should have regular check-ups, blood tests, chest x-rays, and eye exams before and during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets to check for serious side effects.

Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets have not been studied in children.

Who should not take Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

Do not take amiodarone hydrochloride tablets if you:

- have certain heart conditions (heart block, very slow heart rate, or slow heart rate with dizziness or lightheadedness)

- have an allergy to amiodarone, iodine, or any of the other ingredients in amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. See the end of this Medication Guide for a complete list of ingredients in amiodarone hydrochloride tablets.

What should I tell my doctor before starting Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

Tell your doctor about all of your medical conditions including if you:

- have lung or breathing problems

- have liver problems

- have or had thyroid problems

- have blood pressure problems

- are pregnant or planning to become pregnant. Amiodarone can harm your unborn baby. Amiodarone can stay in your body for months after treatment is stopped. Therefore, talk with your doctor before you plan to get pregnant.

- are breastfeeding. Amiodarone passes into your milk and can harm your baby. You should not breast-feed while taking amiodarone. Also, amiodarone can stay in your body for months after treatment is stopped.

Tell your doctor about all the medicines you take including prescription and nonprescription medicines, vitamins and herbal supplements. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets and certain other medicines can interact with each other causing serious side effects. Sometimes the dose of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets or other medicines must be changed when they are used together. Especially, tell your doctor if you are taking:

- antibiotic medicines used to treat infections

- depression medicines

- blood thinner medicines

- HIV or AIDS medicines

- cimetidine (Tagamet®), a medicine for stomach ulcers or indigestion

- loratadine (for example: Claritin®, Alavert®), a medicine for allergy symptoms

- seizure medicines

- diabetes medicines

- cyclosporine, an immunosuppressive medicine

- dextromethorphan, a cough medicine

- medicines for your heart, circulation, or blood pressure

- water pills (diuretics)

- high cholesterol or bile medicines

- narcotic pain medicines

- St. John’s Wort

Know the medicines you take. Keep a list of them with you at all times and show it to your doctor and pharmacist each time you get a new medicine. Do not take any new medicines while you are taking amiodarone hydrochloride tablets unless you have talked with your doctor.

How should I take Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

- Take amiodarone hydrochloride tablets exactly as prescribed by your doctor.

- The dose of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets you take has been specially chosen for you by your doctor and may change during treatment. Keep taking your medicine until your doctor tells you to stop. Do not stop taking it because you feel better. Your condition may get worse. Talk with your doctor if you have side effects.

- Your doctor will tell you to take your dose of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets with or without meals. Make sure you take amiodarone hydrochloride tablets the same way each time.

- Do not drink grapefruit juice during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. Grapefruit juice affects how amiodarone hydrochloride tablets are absorbed in the stomach.

- Taking too many amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can be dangerous. If you take too many amiodarone hydrochloride tablets, call your doctor or go to the nearest hospital right away. You may need medical care right away.

- If you miss a dose, do not take a double dose to make up for the dose you missed. Continue with your next regularly scheduled dose.

What should I avoid while taking Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

- Do not drink grapefruit juice during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. Grapefruit juice affects how amiodarone hydrochloride tablets are absorbed in the stomach.

- Avoid exposing your skin to the sun or sun lamps. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause a photosensitive reaction. Wear sun-block cream or protective clothing when out in the sun.

- Avoid pregnancy during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can harm your unborn baby.

- Do not breastfeed while taking amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. Amiodarone passes into your milk and can harm your baby.

What are the possible or reasonably likely side effects of Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause serious side effects that lead to death including lung damage, liver damage, and worse heartbeat problems and thyroid problems. See "What is the most important information I should know about amiodarone hydrochloride tablets?"

Some other serious side effects of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets include:

- vision problems that may lead to permanent blindness. You should have regular eye exams before and during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. Call your doctor if you have blurred vision, see halos, or your eyes become sensitive to light.

- nerve problems. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause a feeling of "pins and needles" or numbness in the hands, legs, or feet, muscle weakness, uncontrolled movements, poor coordination, and trouble walking.

- thyroid problems. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause thyroid problems, including low thyroid function or overactive thyroid function. Your doctor may arrange regular blood tests to check your thyroid function during treatment with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. Call your doctor if you have weakness, weight loss or weight gain, heat or cold intolerance, hair thinning, sweating, changes in your menses, swelling of your neck (goiter), nervousness, irritability, restlessness, decreased concentration, depression in the elderly, or tremor.

- skin problems. Amiodarone hydrochloride tablets can cause your skin to be more sensitive to the sun or to turn a bluish-gray color. In most patients, skin color slowly returns to normal after stopping amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. In some patients, skin color does not return to normal.

Other side effects of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets include nausea, vomiting, constipation, and loss of appetite.

Call your doctor about any side effect that bothers you.

These are not all the side effects with amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. For more information, ask your doctor or pharmacist.

Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088.

How should I store Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

- Store amiodarone hydrochloride tablets at room temperature. Protect from light. Keep amiodarone hydrochloride tablets in a tightly closed container.

- Safely dispose of amiodarone hydrochloride tablets that are out-of-date or no longer needed.

- Keep amiodarone hydrochloride tablets and all medicines out of the reach of children.

General information about Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use amiodarone hydrochloride tablets for a condition for which it was not prescribed. Do not share amiodarone hydrochloride tablets with other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. It may harm them.

If you have any questions or concerns about amiodarone hydrochloride tablets, ask your doctor or healthcare provider. This Medication Guide summarizes the most important information about amiodarone hydrochloride tablets. If you would like more information, talk with your doctor. You can ask your doctor or pharmacist for information about amiodarone hydrochloride tablets that was written for healthcare professionals. Please address medical inquiries to, (MedicalAffairs@zydususa.com) Tel.: 1-877-993-8779.

What are the ingredients in Amiodarone Hydrochloride Tablets?

Active Ingredient: Amiodarone hydrochloride

Inactive Ingredients: Colloidal silicon dioxide, corn starch, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, povidone and sodium starch glycolate.

This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Tagamet® is a registered trademark of SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals Co.

Claritin® is a registered trademark of Schering Corporation.

Alavert® is a registered trademark of Wyeth.