FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

WARNING: SEVERE HYPOCALCEMIA IN PATIENTS WITH ADVANCED KIDNEY DISEASE

- Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), including dialysis-dependent patients, are at greater risk of severe hypocalcemia following Prolia administration. Severe hypocalcemia resulting in hospitalization, life-threatening events and fatal cases have been reported [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- The presence of chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) markedly increases the risk of hypocalcemia in these patients [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- Prior to initiating Prolia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, evaluate for the presence of CKD-MBD. Treatment with Prolia in these patients should be supervised by a healthcare provider with expertise in the diagnosis and management of CKD-MBD [see Dosage and Administration (2.2) and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

1.1 Treatment of Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis at High Risk for Fracture

Prolia is indicated for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture, defined as a history of osteoporotic fracture, or multiple risk factors for fracture; or patients who have failed or are intolerant to other available osteoporosis therapy. In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, Prolia reduces the incidence of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures [see Clinical Studies (14.1)].

1.2 Treatment to Increase Bone Mass in Men with Osteoporosis

Prolia is indicated for treatment to increase bone mass in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture, defined as a history of osteoporotic fracture, or multiple risk factors for fracture; or patients who have failed or are intolerant to other available osteoporosis therapy [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

1.3 Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis

Prolia is indicated for the treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in men and women at high risk of fracture who are either initiating or continuing systemic glucocorticoids in a daily dosage equivalent to 7.5 mg or greater of prednisone and expected to remain on glucocorticoids for at least 6 months. High risk of fracture is defined as a history of osteoporotic fracture, multiple risk factors for fracture, or patients who have failed or are intolerant to other available osteoporosis therapy [see Clinical Studies (14.3)].

1.4 Treatment of Bone Loss in Men Receiving Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer

Prolia is indicated as a treatment to increase bone mass in men at high risk for fracture receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. In these patients Prolia also reduced the incidence of vertebral fractures [see Clinical Studies (14.4)].

1.5 Treatment of Bone Loss in Women Receiving Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy for Breast Cancer

Prolia is indicated as a treatment to increase bone mass in women at high risk for fracture receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer [see Clinical Studies (14.5)].

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Pregnancy Testing Prior to Initiation of Prolia

Pregnancy must be ruled out prior to administration of Prolia. Perform pregnancy testing in all females of reproductive potential prior to administration of Prolia. Based on findings in animals, Prolia can cause fetal harm when administered to pregnant women [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1, 8.3)].

2.2 Laboratory Testing in Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease Prior to Initiation of Prolia

In patients with advanced chronic kidney disease [i.e., estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2], including dialysis-dependent patients, evaluate for the presence of chronic kidney disease mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) with intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), serum calcium, 25(OH) vitamin D, and 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D prior to decisions regarding Prolia treatment. Consider also assessing bone turnover status (serum markers of bone turnover or bone biopsy) to evaluate the underlying bone disease that may be present [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

2.3 Recommended Dosage

Prolia should be administered by a healthcare professional.

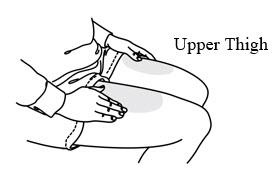

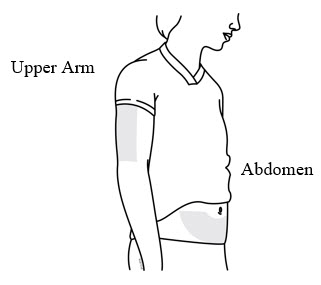

The recommended dose of Prolia is 60 mg administered as a single subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. Administer Prolia via subcutaneous injection in the upper arm, the upper thigh, or the abdomen. All patients should receive calcium 1000 mg daily and at least 400 IU vitamin D daily [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

If a dose of Prolia is missed, administer the injection as soon as the patient is available. Thereafter, schedule injections every 6 months from the date of the last injection.

2.4 Preparation and Administration

Parenteral drug products should be inspected visually for particulate matter and discoloration prior to administration whenever solution and container permit. Prolia is a clear, colorless to pale yellow solution that may contain trace amounts of translucent to white proteinaceous particles. Do not use if the solution is discolored or cloudy or if the solution contains many particles or foreign particulate matter.

Prior to administration, Prolia may be removed from the refrigerator and brought to room temperature (up to 25°C/77°F) by standing in the original container. This generally takes 15 to 30 minutes. Do not warm Prolia in any other way [see How Supplied/Storage and Handling (16)].

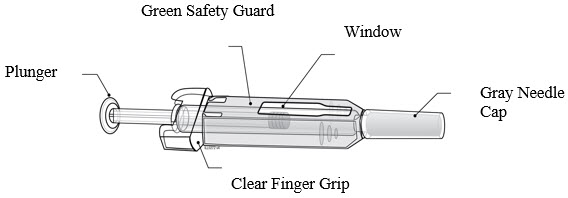

Instructions for Administration of Prolia Prefilled Syringe with Needle Safety Guard

IMPORTANT: In order to minimize accidental needlesticks, the Prolia single-dose prefilled syringe will have a green safety guard; manually activate the safety guard after the injection is given.

DO NOT slide the green safety guard forward over the needle before administering the injection; it will lock in place and prevent injection.

Activate the green safety guard (slide over the needle) after the injection.

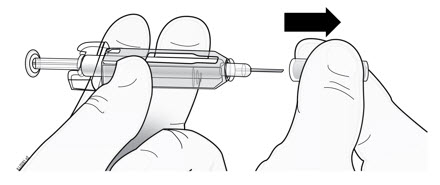

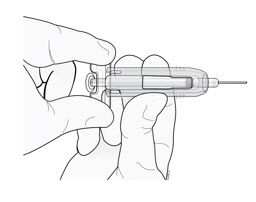

Step 1: Remove Gray Needle Cap

| Remove needle cap. |  |

Step 2: Administer Subcutaneous Injection

| Choose an injection site. The recommended injection sites for Prolia include: the upper arm OR the upper thigh OR the abdomen. |  |

|

|

| Insert needle and inject all the liquid subcutaneously.

Do not administer into muscle or blood vessel. |  |

DO NOT put gray needle cap back on needle.

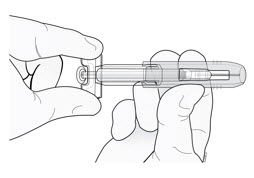

Step 3: Immediately Slide Green Safety Guard Over Needle

With the needle pointing away from you.

Hold the prefilled syringe by the clear finger grip with one hand. Then, with the other hand, grasp the green safety guard by its base and gently slide it towards the needle until the green safety guard locks securely in place and/or you hear a "click". DO NOT grip the green safety guard too firmly - it will move easily if you hold and slide it gently.

| Hold clear finger grip. |  |

|

| Gently slide green safety guard over needle and lock securely in place. Do not grip green safety guard too firmly when sliding over needle. |  |

Immediately dispose of the syringe and needle cap in the nearest sharps container. DO NOT put the needle cap back on the used syringe.

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

- Injection: 1 mL of a 60 mg/mL clear, colorless to pale yellow denosumab solution in a single-dose prefilled syringe.

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

Prolia is contraindicated in:

- Patients with hypocalcemia: Pre-existing hypocalcemia must be corrected prior to initiating therapy with Prolia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

- Pregnant women: Prolia may cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. In women of reproductive potential, pregnancy testing should be performed prior to initiating treatment with Prolia [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

- Patients with hypersensitivity to Prolia: Prolia is contraindicated in patients with a history of systemic hypersensitivity to any component of the product. Reactions have included anaphylaxis, facial swelling, and urticaria [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Adverse Reactions (6.2)].

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Severe Hypocalcemia and Mineral Metabolism Changes

Prolia can cause severe hypocalcemia and fatal cases have been reported. Pre-existing hypocalcemia must be corrected prior to initiating therapy with Prolia. Adequately supplement all patients with calcium and vitamin D [see Dosage and Administration (2.1), Contraindications (4), and Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

In patients without advanced chronic kidney disease who are predisposed to hypocalcemia and disturbances of mineral metabolism (e.g. history of hypoparathyroidism, thyroid surgery, parathyroid surgery, malabsorption syndromes, excision of small intestine, treatment with other calcium-lowering drugs), assess serum calcium and mineral levels (phosphorus and magnesium) 10 to14 days after Prolia injection. In some postmarketing cases, hypocalcemia persisted for weeks or months and required frequent monitoring and intravenous and/or oral calcium replacement, with or without vitamin D.

Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease

Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease [i.e., eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2] including dialysis-dependent patients are at greater risk for severe hypocalcemia following Prolia administration. Severe hypocalcemia resulting in hospitalization, life-threatening events and fatal cases have been reported. The presence of underlying chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD, renal osteodystrophy) markedly increases the risk of hypocalcemia. Concomitant use of calcimimetic drugs may also worsen hypocalcemia risk.

To minimize the risk of hypocalcemia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, evaluate for the presence of chronic kidney disease mineral and bone disorder with intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), serum calcium, 25(OH) vitamin D, and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D prior to decisions regarding Prolia treatment. Consider also assessing bone turnover status (serum markers of bone turnover or bone biopsy) to evaluate the underlying bone disease that may be present. Monitor serum calcium weekly for the first month after Prolia administration and monthly thereafter. Instruct all patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, including those who are dialysis-dependent, about the symptoms of hypocalcemia and the importance of maintaining serum calcium levels with adequate calcium and activated vitamin D supplementation. Treatment with Prolia in these patients should be supervised by a healthcare provider who is experienced in diagnosis and management of CKD-MBD.

5.2 Drug Products with Same Active Ingredient

Prolia contains the same active ingredient (denosumab) found in Xgeva. Patients receiving Prolia should not receive Xgeva.

5.3 Hypersensitivity

Clinically significant hypersensitivity including anaphylaxis has been reported with Prolia. Symptoms have included hypotension, dyspnea, throat tightness, facial and upper airway edema, pruritus, and urticaria. If an anaphylactic or other clinically significant allergic reaction occurs, initiate appropriate therapy, and discontinue further use of Prolia [see Contraindications (4), Adverse Reactions (6.2)].

5.4 Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), which can occur spontaneously, is generally associated with tooth extraction and/or local infection with delayed healing. ONJ has been reported in patients receiving denosumab [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)]. A routine oral exam should be performed by the prescriber prior to initiation of Prolia treatment. A dental examination with appropriate preventive dentistry is recommended prior to treatment with Prolia in patients with risk factors for ONJ such as invasive dental procedures (e.g. tooth extraction, dental implants, oral surgery), diagnosis of cancer, concomitant therapies (e.g. chemotherapy, corticosteroids, angiogenesis inhibitors), poor oral hygiene, and comorbid disorders (e.g. periodontal and/or other pre-existing dental disease, anemia, coagulopathy, infection, ill-fitting dentures). Good oral hygiene practices should be maintained during treatment with Prolia. Concomitant administration of drugs associated with ONJ may increase the risk of developing ONJ. The risk of ONJ may increase with duration of exposure to Prolia.

For patients requiring invasive dental procedures, clinical judgment of the treating physician and/or oral surgeon should guide the management plan of each patient based on individual benefit-risk assessment.

Patients who are suspected of having or who develop ONJ while on Prolia should receive care by a dentist or an oral surgeon. In these patients, extensive dental surgery to treat ONJ may exacerbate the condition. Discontinuation of Prolia therapy should be considered based on individual benefit-risk assessment.

5.5 Atypical Subtrochanteric and Diaphyseal Femoral Fractures

Atypical low energy or low trauma fractures of the shaft have been reported in patients receiving Prolia [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)]. These fractures can occur anywhere in the femoral shaft from just below the lesser trochanter to above the supracondylar flare and are transverse or short oblique in orientation without evidence of comminution. Causality has not been established as these fractures also occur in osteoporotic patients who have not been treated with antiresorptive agents.

Atypical femoral fractures most commonly occur with minimal or no trauma to the affected area. They may be bilateral, and many patients report prodromal pain in the affected area, usually presenting as dull, aching thigh pain, weeks to months before a complete fracture occurs. A number of reports note that patients were also receiving treatment with glucocorticoids (e.g. prednisone) at the time of fracture.

During Prolia treatment, patients should be advised to report new or unusual thigh, hip, or groin pain. Any patient who presents with thigh or groin pain should be suspected of having an atypical fracture and should be evaluated to rule out an incomplete femur fracture. Patient presenting with an atypical femur fracture should also be assessed for symptoms and signs of fracture in the contralateral limb. Interruption of Prolia therapy should be considered, pending a benefit-risk assessment, on an individual basis.

5.6 Multiple Vertebral Fractures (MVF) Following Discontinuation of Prolia Treatment

Following discontinuation of Prolia treatment, fracture risk increases, including the risk of multiple vertebral fractures. Treatment with Prolia results in significant suppression of bone turnover and cessation of Prolia treatment results in increased bone turnover above pretreatment values 9 months after the last dose of Prolia. Bone turnover then returns to pretreatment values 24 months after the last dose of Prolia. In addition, bone mineral density (BMD) returns to pretreatment values within 18 months after the last injection [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2), Clinical Studies (14.1)].

New vertebral fractures occurred as early as 7 months (on average 19 months) after the last dose of Prolia. Prior vertebral fracture was a predictor of multiple vertebral fractures after Prolia discontinuation. Evaluate an individual's benefit-risk before initiating treatment with Prolia.

If Prolia treatment is discontinued, patients should be transitioned to an alternative antiresorptive therapy [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)].

5.7 Serious Infections

In a clinical trial of over 7800 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, serious infections leading to hospitalization were reported more frequently in the Prolia group than in the placebo group [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)]. Serious skin infections, as well as infections of the abdomen, urinary tract, and ear, were more frequent in patients treated with Prolia. Endocarditis was also reported more frequently in Prolia-treated patients. The incidence of opportunistic infections was similar between placebo and Prolia groups, and the overall incidence of infections was similar between the treatment groups. Advise patients to seek prompt medical attention if they develop signs or symptoms of severe infection, including cellulitis.

Patients on concomitant immunosuppressant agents or with impaired immune systems may be at increased risk for serious infections. Consider the benefit-risk profile in such patients before treating with Prolia. In patients who develop serious infections while on Prolia, prescribers should assess the need for continued Prolia therapy.

5.8 Dermatologic Adverse Reactions

In a large clinical trial of over 7800 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, epidermal and dermal adverse events such as dermatitis, eczema, and rashes occurred at a significantly higher rate in the Prolia group compared to the placebo group. Most of these events were not specific to the injection site [see Adverse Reactions (6.1)]. Consider discontinuing Prolia if severe symptoms develop.

5.9 Musculoskeletal Pain

In postmarketing experience, severe and occasionally incapacitating bone, joint, and/or muscle pain has been reported in patients taking Prolia [see Adverse Reactions (6.2)]. The time to onset of symptoms varied from one day to several months after starting Prolia. Consider discontinuing use if severe symptoms develop [see Patient Counseling Information (17)].

5.10 Suppression of Bone Turnover

In clinical trials in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, treatment with Prolia resulted in significant suppression of bone remodeling as evidenced by markers of bone turnover and bone histomorphometry [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.2), Clinical Studies (14.1)]. The significance of these findings and the effect of long-term treatment with Prolia are unknown. The long-term consequences of the degree of suppression of bone remodeling observed with Prolia may contribute to adverse outcomes such as osteonecrosis of the jaw, atypical fractures, and delayed fracture healing. Monitor patients for these consequences.

5.11 Hypercalcemia in Pediatric Patients with Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Prolia is not approved for use in pediatric patients. Hypercalcemia has been reported in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta treated with denosumab products, including Prolia. Some cases required hospitalization [see Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following serious adverse reactions are discussed below and also elsewhere in the labeling:

- Hypocalcemia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Serious Infections [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Dermatologic Adverse Reactions [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

- Osteonecrosis of the Jaw [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Atypical Subtrochanteric and Diaphyseal Femoral Fractures [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Multiple Vertebral Fractures (MVF) Following Discontinuation of Prolia Treatment [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

The most common adverse reactions reported with Prolia in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis are back pain, pain in extremity, musculoskeletal pain, hypercholesterolemia, and cystitis.

The most common adverse reactions reported with Prolia in men with osteoporosis are back pain, arthralgia, and nasopharyngitis.

The most common adverse reactions reported with Prolia in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis are back pain, hypertension, bronchitis, and headache.

The most common (per patient incidence ≥ 10%) adverse reactions reported with Prolia in patients with bone loss receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer or adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer are arthralgia and back pain. Pain in extremity and musculoskeletal pain have also been reported in clinical trials.

The most common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation of Prolia in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis are back pain and constipation.

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical studies are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical studies of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical studies of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in clinical practice.

Treatment of Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis

The safety of Prolia in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis was assessed in a 3-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study of 7808 postmenopausal women aged 60 to 91 years. A total of 3876 women were exposed to placebo and 3886 women were exposed to Prolia administered subcutaneously once every 6 months as a single 60 mg dose. All women were instructed to take at least 1000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation per day.

The incidence of all-cause mortality was 2.3% (n = 90) in the placebo group and 1.8% (n = 70) in the Prolia group. The incidence of nonfatal serious adverse events was 24.2% in the placebo group and 25.0% in the Prolia group. The percentage of patients who withdrew from the study due to adverse events was 2.1% and 2.4% for the placebo and Prolia groups, respectively. The most common adverse reactions reported with Prolia in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis are back pain, pain in extremity, musculoskeletal pain, hypercholesterolemia, and cystitis.

Adverse reactions reported in ≥ 2% of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and more frequently in the Prolia-treated women than in the placebo-treated women are shown in the table below.

| Preferred Term | Prolia (N = 3886) n (%) | Placebo (N = 3876) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Back pain | 1347 (34.7) | 1340 (34.6) |

| Pain in extremity | 453 (11.7) | 430 (11.1) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 297 (7.6) | 291 (7.5) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 280 (7.2) | 236 (6.1) |

| Cystitis | 228 (5.9) | 225 (5.8) |

| Vertigo | 195 (5.0) | 187 (4.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 190 (4.9) | 167 (4.3) |

| Edema peripheral | 189 (4.9) | 155 (4.0) |

| Sciatica | 178 (4.6) | 149 (3.8) |

| Bone pain | 142 (3.7) | 117 (3.0) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 129 (3.3) | 111 (2.9) |

| Anemia | 129 (3.3) | 107 (2.8) |

| Insomnia | 126 (3.2) | 122 (3.1) |

| Myalgia | 114 (2.9) | 94 (2.4) |

| Angina pectoris | 101 (2.6) | 87 (2.2) |

| Rash | 96 (2.5) | 79 (2.0) |

| Pharyngitis | 91 (2.3) | 78 (2.0) |

| Asthenia | 90 (2.3) | 73 (1.9) |

| Pruritus | 87 (2.2) | 82 (2.1) |

| Flatulence | 84 (2.2) | 53 (1.4) |

| Spinal osteoarthritis | 82 (2.1) | 64 (1.7) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 80 (2.1) | 66 (1.7) |

| Herpes zoster | 79 (2.0) | 72 (1.9) |

Hypocalcemia

Decreases in serum calcium levels to less than 8.5 mg/dL at any visit were reported in 0.4% women in the placebo group and 1.7% women in the Prolia group. The nadir in serum calcium level occurred at approximately day 10 after Prolia dosing in subjects with normal renal function.

In clinical studies, subjects with impaired renal function were more likely to have greater reductions in serum calcium levels compared to subjects with normal renal function. In a study of 55 subjects with varying degrees of renal function, serum calcium levels < 7.5 mg/dL or symptomatic hypocalcemia were observed in 5 subjects. These included no subjects in the normal renal function group, 10% of subjects in the creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min group, 29% of subjects in the creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min group, and 29% of subjects in the hemodialysis group. These subjects did not receive calcium and vitamin D supplementation. In a study of 4550 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, the mean change from baseline in serum calcium level 10 days after Prolia dosing was -5.5% in subjects with creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min vs. -3.1% in subjects with creatinine clearance ≥ 30 mL/min.

Serious Infections

Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) is expressed on activated T and B lymphocytes and in lymph nodes. Therefore, a RANKL inhibitor such as Prolia may increase the risk of infection.

In the clinical study of 7808 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, the incidence of infections resulting in death was 0.2% in both placebo and Prolia treatment groups. However, the incidence of nonfatal serious infections was 3.3% in the placebo and 4.0% in the Prolia groups. Hospitalizations due to serious infections in the abdomen (0.7% placebo vs. 0.9% Prolia), urinary tract (0.5% placebo vs. 0.7% Prolia), and ear (0.0% placebo vs. 0.1% Prolia) were reported. Endocarditis was reported in no placebo patients and 3 patients receiving Prolia.

Skin infections, including erysipelas and cellulitis, leading to hospitalization were reported more frequently in patients treated with Prolia (< 0.1% placebo vs. 0.4% Prolia).

The incidence of opportunistic infections was similar to that reported with placebo.

Dermatologic Adverse Reactions

A significantly higher number of patients treated with Prolia developed epidermal and dermal adverse events (such as dermatitis, eczema, and rashes), with these events reported in 8.2% of the placebo and 10.8% of the Prolia groups (p < 0.0001). Most of these events were not specific to the injection site [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

ONJ has been reported in the osteoporosis clinical trial program in patients treated with Prolia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

Atypical Subtrochanteric and Diaphyseal Femoral Fractures

In the osteoporosis clinical trial program, atypical femoral fractures were reported in patients treated with Prolia. The duration of Prolia exposure to time of atypical femoral fracture diagnosis was as early as 2½ years [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)].

Multiple Vertebral Fractures (MVF) Following Discontinuation of Prolia Treatment

In the osteoporosis clinical trial program, multiple vertebral fractures were reported in patients after discontinuation of Prolia. In the phase 3 trial in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, 6% of women who discontinued Prolia and remained in the study developed new vertebral fractures, and 3% of women who discontinued Prolia and remained in the study developed multiple new vertebral fractures. The mean time to onset of multiple vertebral fractures was 17 months (range: 7-43 months) after the last injection of Prolia. Prior vertebral fracture was a predictor of multiple vertebral fractures after discontinuation [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis was reported in 4 patients (0.1%) in the placebo and 8 patients (0.2%) in the Prolia groups. Of these reports, 1 patient in the placebo group and all 8 patients in the Prolia group had serious events, including one death in the Prolia group. Several patients had a prior history of pancreatitis. The time from product administration to event occurrence was variable.

New Malignancies

The overall incidence of new malignancies was 4.3% in the placebo and 4.8% in the Prolia groups. New malignancies related to the breast (0.7% placebo vs. 0.9% Prolia), reproductive system (0.2% placebo vs. 0.5% Prolia), and gastrointestinal system (0.6% placebo vs. 0.9% Prolia) were reported. A causal relationship to drug exposure has not been established.

Treatment to Increase Bone Mass in Men with Osteoporosis

The safety of Prolia in the treatment of men with osteoporosis was assessed in a 1-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. A total of 120 men were exposed to placebo and 120 men were exposed to Prolia administered subcutaneously once every 6 months as a single 60 mg dose. All men were instructed to take at least 1000 mg of calcium and 800 IU of vitamin D supplementation per day.

The incidence of all-cause mortality was 0.8% (n = 1) in the placebo group and 0.8% (n = 1) in the Prolia group. The incidence of nonfatal serious adverse events was 7.5% in the placebo group and 8.3% in the Prolia group. The percentage of patients who withdrew from the study due to adverse events was 0% and 2.5% for the placebo and Prolia groups, respectively.

Adverse reactions reported in ≥ 5% of men with osteoporosis and more frequently with Prolia than in the placebo-treated patients were: back pain (6.7% placebo vs. 8.3% Prolia), arthralgia (5.8% placebo vs. 6.7% Prolia), and nasopharyngitis (5.8% placebo vs. 6.7% Prolia).

Serious Infections

Serious infection was reported in 1 patient (0.8%) in the placebo group and no patients in the Prolia group.

Dermatologic Adverse Reactions

Epidermal and dermal adverse events (such as dermatitis, eczema, and rashes) were reported in 4 patients (3.3%) in the placebo group and 5 patients (4.2%) in the Prolia group.

Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis

The safety of Prolia in the treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis was assessed in the 1-year, primary analysis of a 2-year randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, active-controlled study of 795 patients (30% men and 70% women) aged 20 to 94 (mean age of 63 years) treated with greater than or equal to 7.5 mg/day oral prednisone (or equivalent). A total of 384 patients were exposed to 5 mg oral daily bisphosphonate (active-control) and 394 patients were exposed to Prolia administered once every 6 months as a 60 mg subcutaneous dose. All patients were instructed to take at least 1000 mg of calcium and 800 IU of vitamin D supplementation per day.

The incidence of all-cause mortality was 0.5% (n = 2) in the active-control group and 1.5% (n = 6) in the Prolia group. The incidence of serious adverse events was 17% in the active-control group and 16% in the Prolia group. The percentage of patients who withdrew from the study due to adverse events was 3.6% and 3.8% for the active-control and Prolia groups, respectively.

Adverse reactions reported in ≥ 2% of patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and more frequently with Prolia than in the active-control-treated patients are shown in the table below.

| Preferred Term | Prolia (N = 394) n (%) | Oral Daily Bisphosphonate (Active-Control) (N = 384) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Back pain | 18 (4.6) | 17 (4.4) |

| Hypertension | 15 (3.8) | 13 (3.4) |

| Bronchitis | 15 (3.8) | 11 (2.9) |

| Headache | 14 (3.6) | 7 (1.8) |

| Dyspepsia | 12 (3.0) | 10 (2.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 12 (3.0) | 8 (2.1) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 12 (3.0) | 7 (1.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 11 (2.8) | 10 (2.6) |

| Constipation | 11 (2.8) | 6 (1.6) |

| Vomiting | 10 (2.5) | 6 (1.6) |

| Dizziness | 9 (2.3) | 8 (2.1) |

| Fall | 8 (2.0) | 7 (1.8) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica* | 8 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) |

Atypical Subtrochanteric and Diaphyseal Femoral Fractures

Atypical femoral fractures were reported in 1 patient treated with Prolia. The duration of Prolia exposure to time of atypical femoral fracture diagnosis was at 8.0 months [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)].

Treatment of Bone Loss in Patients Receiving Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer or Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy for Breast Cancer

The safety of Prolia in the treatment of bone loss in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was assessed in a 3-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study of 1468 men aged 48 to 97 years. A total of 725 men were exposed to placebo and 731 men were exposed to Prolia administered once every 6 months as a single 60 mg subcutaneous dose. All men were instructed to take at least 1000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation per day.

The incidence of serious adverse events was 30.6% in the placebo group and 34.6% in the Prolia group. The percentage of patients who withdrew from the study due to adverse events was 6.1% and 7.0% for the placebo and Prolia groups, respectively.

The safety of Prolia in the treatment of bone loss in women with nonmetastatic breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy was assessed in a 2-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study of 252 postmenopausal women aged 35 to 84 years. A total of 120 women were exposed to placebo and 129 women were exposed to Prolia administered once every 6 months as a single 60 mg subcutaneous dose. All women were instructed to take at least 1000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation per day.

The incidence of serious adverse events was 9.2% in the placebo group and 14.7% in the Prolia group. The percentage of patients who withdrew from the study due to adverse events was 4.2% and 0.8% for the placebo and Prolia groups, respectively.

Adverse reactions reported in ≥ 10% of Prolia-treated patients receiving ADT for prostate cancer or adjuvant AI therapy for breast cancer, and more frequently than in the placebo-treated patients were: arthralgia (13.0% placebo vs. 14.3% Prolia) and back pain (10.5% placebo vs. 11.5% Prolia). Pain in extremity (7.7% placebo vs. 9.9% Prolia) and musculoskeletal pain (3.8% placebo vs. 6.0% Prolia) have also been reported in clinical trials. Additionally, in Prolia-treated men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer receiving ADT, a greater incidence of cataracts was observed (1.2% placebo vs. 4.7% Prolia). Hypocalcemia (serum calcium < 8.4 mg/dL) was reported only in Prolia-treated patients (2.4% vs. 0.0%) at the month 1 visit.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

Because postmarketing reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post approval use of Prolia:

- Drug-related hypersensitivity reactions: anaphylaxis, rash, urticaria, facial swelling, and erythema

- Hypocalcemia: severe symptomatic hypocalcemia resulting in hospitalization, life-threatening events, and fatal cases

- Musculoskeletal pain, including severe cases

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH): Marked elevation in serum PTH in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) or receiving dialysis

- Multiple vertebral fractures following discontinuation of Prolia

- Cutaneous and mucosal lichenoid drug eruptions (e.g., lichen planus-like reactions)

- Alopecia

- Vasculitis (e.g. ANCA positive vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis)

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Risk Summary

Prolia is contraindicated for use in pregnant women because it may cause harm to a fetus. There are insufficient data with denosumab use in pregnant women to inform any drug-associated risks for adverse developmental outcomes. In utero denosumab exposure from cynomolgus monkeys dosed monthly with denosumab throughout pregnancy at a dose 50-fold higher than the recommended human dose based on body weight resulted in increased fetal loss, stillbirths, and postnatal mortality, and absent lymph nodes, abnormal bone growth, and decreased neonatal growth [see Data].

Data

Animal Data

The effects of denosumab on prenatal development have been studied in both cynomolgus monkeys and genetically engineered mice in which RANK ligand (RANKL) expression was turned off by gene removal (a "knockout mouse"). In cynomolgus monkeys dosed subcutaneously with denosumab throughout pregnancy starting at gestational day 20 and at a pharmacologically active dose 50-fold higher than the recommended human dose based on body weight, there was increased fetal loss during gestation, stillbirths, and postnatal mortality. Other findings in offspring included absence of axillary, inguinal, mandibular, and mesenteric lymph nodes; abnormal bone growth, reduced bone strength, reduced hematopoiesis, dental dysplasia, and tooth malalignment; and decreased neonatal growth. At birth out to 1 month of age, infants had measurable blood levels of denosumab (22-621% of maternal levels).

Following a recovery period from birth out to 6 months of age, the effects on bone quality and strength returned to normal; there were no adverse effects on tooth eruption, though dental dysplasia was still apparent; axillary and inguinal lymph nodes remained absent, while mandibular and mesenteric lymph nodes were present, though small; and minimal to moderate mineralization in multiple tissues was seen in one recovery animal. There was no evidence of maternal harm prior to labor; adverse maternal effects occurred infrequently during labor. Maternal mammary gland development was normal. There was no fetal NOAEL (no observable adverse effect level) established for this study because only one dose of 50 mg/kg was evaluated. Mammary gland histopathology at 6 months of age was normal in female offspring exposed to denosumab in utero; however, development and lactation have not been fully evaluated.

In RANKL knockout mice, absence of RANKL (the target of denosumab) also caused fetal lymph node agenesis and led to postnatal impairment of dentition and bone growth. Pregnant RANKL knockout mice showed altered maturation of the maternal mammary gland, leading to impaired lactation [see Use in Specific Populations (8.2), Nonclinical Toxicology (13.2)].

The no effect dose for denosumab-induced teratogenicity is unknown. However, a Cmax of 22.9 ng/mL was identified in cynomolgus monkeys as a level in which no biologic effects (NOEL) of denosumab were observed (no inhibition of RANKL) [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

There is no information regarding the presence of denosumab in human milk, the effects on the breastfed infant, or the effects on milk production. Denosumab was detected in the maternal milk of cynomolgus monkeys up to 1 month after the last dose of denosumab (≤ 0.5% milk:serum ratio) and maternal mammary gland development was normal, with no impaired lactation. However, pregnant RANKL knockout mice showed altered maturation of the maternal mammary gland, leading to impaired lactation [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1), Nonclinical Toxicology (13.2)].

8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Based on findings in animals, Prolia can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

Pregnancy Testing

Verify the pregnancy status of females of reproductive potential prior to initiating Prolia treatment.

Contraception

Females

Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during therapy, and for at least 5 months after the last dose of Prolia.

Males

Denosumab was present at low concentrations (approximately 2% of serum exposure) in the seminal fluid of male subjects given Prolia. Following vaginal intercourse, the maximum amount of denosumab delivered to a female partner would result in exposures approximately 11000 times lower than the prescribed 60 mg subcutaneous dose, and at least 38 times lower than the NOEL in monkeys.

Therefore, male condom use would not be necessary as it is unlikely that a female partner or fetus would be exposed to pharmacologically relevant concentrations of denosumab via seminal fluid [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.4 Pediatric Use

The safety and effectiveness of Prolia have not been established in pediatric patients.

In one multicenter, open-label study conducted in 153 pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta, aged 2 to 17 years, evaluating fracture risk reduction, efficacy was not established.

Hypercalcemia has been reported in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta treated with denosumab products, including Prolia. Some cases required hospitalization and were complicated by acute renal injury [see Warnings and Precautions (5.11)]. Clinical studies in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta were terminated early due to the occurrence of life-threatening events and hospitalizations due to hypercalcemia.

Based on results from animal studies, Prolia may negatively affect long-bone growth and dentition in pediatric patients below the age of 4 years.

Juvenile Animal Toxicity Data

Treatment with Prolia may impair long-bone growth in children with open growth plates and may inhibit eruption of dentition. In neonatal rats, inhibition of RANKL (the target of Prolia therapy) with a construct of osteoprotegerin bound to Fc (OPG-Fc) at doses ≤ 10 mg/kg was associated with inhibition of bone growth and tooth eruption. Adolescent primates treated with denosumab at doses 10 and 50 times (10 and 50 mg/kg dose) higher than the recommended human dose of 60 mg administered every 6 months, based on body weight (mg/kg), had abnormal growth plates, considered to be consistent with the pharmacological activity of denosumab [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.2)].

Cynomolgus monkeys exposed in utero to denosumab exhibited bone abnormalities, an absence of axillary, inguinal, mandibular, and mesenteric lymph nodes, reduced hematopoiesis, tooth malalignment, and decreased neonatal growth. Some bone abnormalities recovered once exposure was ceased following birth; however, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes remained absent 6 months post-birth [see Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

8.5 Geriatric Use

Of the total number of patients in clinical studies of Prolia, 9943 patients (76%) were ≥ 65 years old, while 3576 (27%) were ≥ 75 years old. Of the patients in the osteoporosis study in men, 133 patients (55%) were ≥ 65 years old, while 39 patients (16%) were ≥ 75 years old. Of the patients in the glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis study, 355 patients (47%) were ≥ 65 years old, while 132 patients (17%) were ≥ 75 years old. No overall differences in safety or efficacy were observed between these patients and younger patients, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out.

8.6 Renal Impairment

No dose adjustment is necessary in patients with renal impairment.

Severe hypocalcemia resulting in hospitalization, life-threatening events and fatal cases have been reported postmarketing. In clinical studies, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (i.e., eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), including dialysis-dependent patients, were at greater risk of developing hypocalcemia. The presence of underlying chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD, renal osteodystrophy) markedly increases the risk of hypocalcemia. Concomitant use of calcimimetic drugs may also worsen hypocalcemia risk. Consider the benefits and risks to the patient when administering Prolia to patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Monitor calcium and mineral levels (phosphorus and magnesium). Adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D is important in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease including dialysis-dependent patients [see Dosage and Administration (2.2),Warnings and Precautions (5.1), Adverse Reactions (6.1) and Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

11 DESCRIPTION

Denosumab is a human IgG2 monoclonal antibody with affinity and specificity for human RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand). Denosumab has an approximate molecular weight of 147 kDa and is produced in genetically engineered mammalian (Chinese hamster ovary) cells.

Prolia (denosumab) injection is a sterile, preservative-free, clear, colorless to pale yellow solution for subcutaneous use.

Each 1 mL single-dose prefilled syringe of Prolia contains 60 mg denosumab (60 mg/mL solution), 4.7% sorbitol, 17 mM acetate, 0.01% polysorbate 20, Water for Injection (USP), and sodium hydroxide to a pH of 5.2.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

Prolia binds to RANKL, a transmembrane or soluble protein essential for the formation, function, and survival of osteoclasts, the cells responsible for bone resorption. Prolia prevents RANKL from activating its receptor, RANK, on the surface of osteoclasts and their precursors. Prevention of the RANKL/RANK interaction inhibits osteoclast formation, function, and survival, thereby decreasing bone resorption and increasing bone mass and strength in both cortical and trabecular bone.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

In clinical studies, treatment with 60 mg of Prolia resulted in reduction in the bone resorption marker serum type 1 C-telopeptide (CTX) by approximately 85% by 3 days, with maximal reductions occurring by 1 month. CTX levels were below the limit of assay quantitation (0.049 ng/mL) in 39% to 68% of patients 1 to 3 months after dosing of Prolia. At the end of each dosing interval, CTX reductions were partially attenuated from a maximal reduction of ≥ 87% to ≥ 45% (range: 45% to 80%), as serum denosumab levels diminished, reflecting the reversibility of the effects of Prolia on bone remodeling. These effects were sustained with continued treatment. Upon reinitiation, the degree of inhibition of CTX by Prolia was similar to that observed in patients initiating Prolia treatment.

Consistent with the physiological coupling of bone formation and resorption in skeletal remodeling, subsequent reductions in bone formation markers (i.e., osteocalcin and procollagen type 1 N-terminal peptide [P1NP]) were observed starting 1 month after the first dose of Prolia. After discontinuation of Prolia therapy, markers of bone resorption increased to levels 40% to 60% above pretreatment values but returned to baseline levels within 12 months.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

In a study conducted in healthy male and female volunteers (n = 73, age range: 18 to 64 years) following a single subcutaneously administered Prolia dose of 60 mg, the mean area-under-the-concentration-time curve up to 16 weeks (AUC0-16 weeks) of denosumab was 316 mcg∙day/mL (SD = 101 mcg∙day/mL). The mean maximum denosumab concentration (Cmax) was 6.75 mcg/mL (SD = 1.89 mcg/mL). No accumulation or change in denosumab pharmacokinetics with time is observed with multiple dosing of 60 mg subcutaneously administered once every 6 months.

Absorption

Following subcutaneous administration, the median time to maximum denosumab concentration (Tmax) was 10 days (range: 3 to 21 days).

Elimination

Serum denosumab concentrations declined over a period of 4 to 5 months with a mean half-life of 25.4 days (SD = 8.5 days; n = 46).

A population pharmacokinetic analysis was performed to evaluate the effects of demographic characteristics. This analysis showed no notable differences in pharmacokinetics with age (in postmenopausal women), race, or body weight (36 to 140 kg).

Seminal Fluid Pharmacokinetic Study

Serum and seminal fluid concentrations of denosumab were measured in 12 healthy male volunteers (age range: 43-65 years). After a single 60 mg subcutaneous administration of denosumab, the mean (± SD) Cmax values in the serum and seminal fluid samples were 6170 (± 2070) and 100 (± 81.9) ng/mL, respectively, resulting in a maximum seminal fluid concentration of approximately 2% of serum levels. The median (range) Tmax values in the serum and seminal fluid samples were 8.0 (7.9 to 21) and 21 (8.0 to 49) days, respectively. Among the subjects, the highest denosumab concentration in seminal fluid was 301 ng/mL at 22 days post-dose. On the first day of measurement (10 days post-dose), nine of eleven subjects had quantifiable concentrations in semen. On the last day of measurement (106 days post-dose), five subjects still had quantifiable concentrations of denosumab in seminal fluid, with a mean (± SD) seminal fluid concentration of 21.1 (± 36.5) ng/mL across all subjects (n = 12).

Drug Interactions

In a study of 19 postmenopausal women with low BMD and rheumatoid arthritis treated with etanercept (50 mg subcutaneous injection once weekly), a single-dose of denosumab (60 mg subcutaneous injection) was administered 7 days after the previous dose of etanercept. No clinically significant changes in the pharmacokinetics of etanercept were observed.

Cytochrome P450 substrates

In a study of 17 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, midazolam (2 mg oral) was administered 2 weeks after a single-dose of denosumab (60 mg subcutaneous injection), which approximates the Tmax of denosumab. Denosumab did not affect the pharmacokinetics of midazolam, which is metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). This indicates that denosumab should not alter the pharmacokinetics of drugs metabolized by CYP3A4 in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Specific Populations

Gender: Mean serum denosumab concentration-time profiles observed in a study conducted in healthy men ≥ 50 years were similar to those observed in a study conducted in postmenopausal women using the same dose regimen.

Age: The pharmacokinetics of denosumab were not affected by age across all populations studied whose ages ranged from 28 to 87 years.

12.6 Immunogenicity

The observed incidence of anti-drug antibody is highly dependent on the sensitivity and specificity of the assay. Differences in assay methods preclude meaningful comparisons of the incidence of anti-drug antibodies in the studies described below with the incidence of anti-drug antibodies in other studies, including those of Prolia or denosumab products.

Using an electrochemiluminescent bridging immunoassay, less than 1% (55 out of 8113) of patients treated with Prolia for up to 5 years tested positive for binding antibodies (including pre-existing, transient, and developing antibodies). None of the patients tested positive for neutralizing antibodies, as was assessed using a chemiluminescent cell-based in vitro biological assay.

There was no identified clinically significant effect of anti-drug antibodies on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, or effectiveness of denosumab.

13 NONCLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

13.2 Animal Toxicology and/or Pharmacology

Denosumab is an inhibitor of osteoclastic bone resorption via inhibition of RANKL.

In ovariectomized monkeys, once-monthly treatment with denosumab suppressed bone turnover and increased BMD and strength of cancellous and cortical bone at doses 50-fold higher than the recommended human dose of 60 mg administered once every 6 months, based on body weight (mg/kg). Bone tissue was normal with no evidence of mineralization defects, accumulation of osteoid, or woven bone.

Because the biological activity of denosumab in animals is specific to nonhuman primates, evaluation of genetically engineered ("knockout") mice or use of other biological inhibitors of the RANK/RANKL pathway, namely OPG-Fc, provided additional information on the pharmacodynamic properties of denosumab. RANK/RANKL knockout mice exhibited absence of lymph node formation, as well as an absence of lactation due to inhibition of mammary gland maturation (lobulo-alveolar gland development during pregnancy). Neonatal RANK/RANKL knockout mice exhibited reduced bone growth and lack of tooth eruption. A corroborative study in 2-week-old rats given the RANKL inhibitor OPG-Fc also showed reduced bone growth, altered growth plates, and impaired tooth eruption. These changes were partially reversible in this model when dosing with the RANKL inhibitors was discontinued.

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

14.1 Treatment of Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis

The efficacy and safety of Prolia in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis was demonstrated in a 3-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Enrolled women had a baseline BMD T-score between -2.5 and -4.0 at either the lumbar spine or total hip. Women with other diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Paget's disease) or on therapies that affect bone were excluded from this study. The 7808 enrolled women were aged 60 to 91 years with a mean age of 72 years. Overall, the mean baseline lumbar spine BMD T-score was -2.8, and 23% of women had a vertebral fracture at baseline. Women were randomized to receive subcutaneous injections of either placebo (N = 3906) or Prolia 60 mg (N = 3902) once every 6 months. All women received at least 1000 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D supplementation daily.

The primary efficacy variable was the incidence of new morphometric (radiologically-diagnosed) vertebral fractures at 3 years. Vertebral fractures were diagnosed based on lateral spine radiographs (T4-L4) using a semiquantitative scoring method. Secondary efficacy variables included the incidence of hip fracture and nonvertebral fracture, assessed at 3 years.

Effect on Vertebral Fractures

Prolia significantly reduced the incidence of new morphometric vertebral fractures at 1, 2, and 3 years (p < 0.0001), as shown in Table 3. The incidence of new vertebral fractures at year 3 was 7.2% in the placebo-treated women compared to 2.3% for the Prolia-treated women. The absolute risk reduction was 4.8% and relative risk reduction was 68% for new morphometric vertebral fractures at year 3.

| Proportion of Women with Fracture (%)* | Absolute Risk Reduction (%)†

(95% CI) | Relative Risk Reduction (%)†

(95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo N = 3691 (%) | Prolia N = 3702 (%) |

|||

| 0-1 Year | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.4 (0.8, 1.9) | 61 (42, 74) |

| 0-2 Years | 5.0 | 1.4 | 3.5 (2.7, 4.3) | 71 (61, 79) |

| 0-3 Years | 7.2 | 2.3 | 4.8 (3.9, 5.8) | 68 (59, 74) |

Prolia was effective in reducing the risk for new morphometric vertebral fractures regardless of age, baseline rate of bone turnover, baseline BMD, baseline history of fracture, or prior use of a drug for osteoporosis.

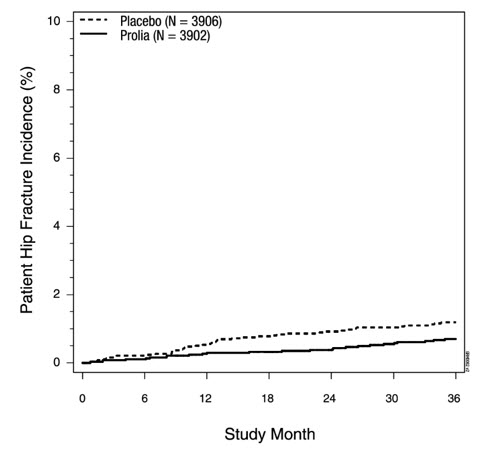

Effect on Hip Fractures

The incidence of hip fracture was 1.2% for placebo-treated women compared to 0.7% for Prolia-treated women at year 3. The age-adjusted absolute risk reduction of hip fractures was 0.3% with a relative risk reduction of 40% at 3 years (p = 0.04) ( see Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Hip Fractures Over 3 Years |

|

| N = number of subjects randomized |

Effect on Nonvertebral Fractures

Treatment with Prolia resulted in a significant reduction in the incidence of nonvertebral fractures (see Table 4).

| Proportion of Women with Fracture (%)* | Absolute Risk Reduction (%) (95% CI) | Relative Risk Reduction (%) (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo N = 3906 (%) | Prolia N = 3902 (%) |

|||

| Nonvertebral fracture† | 8.0 | 6.5 | 1.5 (0.3, 2.7) | 20 (5, 33)‡ |

Effect on Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Treatment with Prolia significantly increased BMD at all anatomic sites measured at 3 years. The treatment differences in BMD at 3 years were 8.8% at the lumbar spine, 6.4% at the total hip, and 5.2% at the femoral neck. Consistent effects on BMD were observed at the lumbar spine, regardless of baseline age, race, weight/body mass index (BMI), baseline BMD, and level of bone turnover.

After Prolia discontinuation, BMD returned to approximately baseline levels within 12 months.

Bone Histology and Histomorphometry

A total of 115 transiliac crest bone biopsy specimens were obtained from 92 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at either month 24 and/or month 36 (53 specimens in Prolia group, 62 specimens in placebo group). Of the biopsies obtained, 115 (100%) were adequate for qualitative histology and 7 (6%) were adequate for full quantitative histomorphometry assessment.

Qualitative histology assessments showed normal architecture and quality with no evidence of mineralization defects, woven bone, or marrow fibrosis in patients treated with Prolia.

The presence of double tetracycline labeling in a biopsy specimen provides an indication of active bone remodeling, while the absence of tetracycline label suggests suppressed bone formation. In patients treated with Prolia, 35% had no tetracycline label present at the month 24 biopsy and 38% had no tetracycline label present at the month 36 biopsy, while 100% of placebo-treated patients had double label present at both time points. When compared to placebo, treatment with Prolia resulted in virtually absent activation frequency and markedly reduced bone formation rates. However, the long-term consequences of this degree of suppression of bone remodeling are unknown.

14.2 Treatment to Increase Bone Mass in Men with Osteoporosis

The efficacy and safety of Prolia in the treatment to increase bone mass in men with osteoporosis was demonstrated in a 1-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Enrolled men had a baseline BMD T-score between -2.0 and -3.5 at the lumbar spine or femoral neck. Men with a BMD T-score between -1.0 and -3.5 at the lumbar spine or femoral neck were also enrolled if there was a history of prior fragility fracture. Men with other diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Paget's disease) or on therapies that may affect bone were excluded from this study. The 242 men enrolled in the study ranged in age from 31 to 84 years with a mean age of 65 years. Men were randomized to receive SC injections of either placebo (n = 121) or Prolia 60 mg (n = 121) once every 6 months. All men received at least 1000 mg calcium and at least 800 IU vitamin D supplementation daily.

Effect on Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

The primary efficacy variable was percent change in lumbar spine BMD from baseline to 1-year. Secondary efficacy variables included percent change in total hip, and femoral neck BMD from baseline to 1-year.

Treatment with Prolia significantly increased BMD at 1-year. The treatment differences in BMD at 1-year were 4.8% (+0.9% placebo, +5.7% Prolia; (95% CI: 4.0, 5.6); p < 0.0001) at the lumbar spine, 2.0% (+0.3% placebo, +2.4% Prolia) at the total hip, and 2.2% (0.0% placebo, +2.1% Prolia) at femoral neck. Consistent effects on BMD were observed at the lumbar spine regardless of baseline age, race, BMD, testosterone concentrations, and level of bone turnover.

Bone Histology and Histomorphometry

A total of 29 transiliac crest bone biopsy specimens were obtained from men with osteoporosis at 12 months (17 specimens in Prolia group, 12 specimens in placebo group). Of the biopsies obtained, 29 (100%) were adequate for qualitative histology and, in Prolia patients, 6 (35%) were adequate for full quantitative histomorphometry assessment. Qualitative histology assessments showed normal architecture and quality with no evidence of mineralization defects, woven bone, or marrow fibrosis in patients treated with Prolia. The presence of double tetracycline labeling in a biopsy specimen provides an indication of active bone remodeling, while the absence of tetracycline label suggests suppressed bone formation. In patients treated with Prolia, 6% had no tetracycline label present at the month 12 biopsy, while 100% of placebo-treated patients had double label present. When compared to placebo, treatment with Prolia resulted in markedly reduced bone formation rates. However, the long-term consequences of this degree of suppression of bone remodeling are unknown.

14.3 Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis

The efficacy and safety of Prolia in the treatment of patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis was assessed in the 12-month primary analysis of a 2-year, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, active-controlled study (NCT 01575873) of 795 patients (70% women and 30% men) aged 20 to 94 years (mean age of 63 years) treated with greater than or equal to 7.5 mg/day oral prednisone (or equivalent) for < 3 months prior to study enrollment and planning to continue treatment for a total of at least 6 months (glucocorticoid-initiating subpopulation; n = 290) or ≥ 3 months prior to study enrollment and planning to continue treatment for a total of at least 6 months (glucocorticoid-continuing subpopulation, n = 505). Enrolled patients < 50 years of age were required to have a history of osteoporotic fracture. Enrolled patients ≥ 50 years of age who were in the glucocorticoid-continuing subpopulation were required to have a baseline BMD T-score of ≤ -2.0 at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck; or a BMD T-score ≤ -1.0 at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck and a history of osteoporotic fracture.

Patients were randomized (1:1) to receive either an oral daily bisphosphonate (active-control, risedronate 5 mg once daily) (n = 397) or Prolia 60 mg subcutaneously once every 6 months (n = 398) for one year. Randomization was stratified by gender within each subpopulation. Patients received at least 1000 mg calcium and 800 IU vitamin D supplementation daily.

Effect on Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

In the glucocorticoid-initiating subpopulation, Prolia significantly increased lumbar spine BMD compared to the active-control at one year (Active-control 0.8%, Prolia 3.8%) with a treatment difference of 2.9% (p < 0.001). In the glucocorticoid-continuing subpopulation, Prolia significantly increased lumbar spine BMD compared to active-control at one year (Active-control 2.3%, Prolia 4.4%) with a treatment difference of 2.2% (p < 0.001). Consistent effects on lumbar spine BMD were observed regardless of gender; race; geographic region; menopausal status; and baseline age, lumbar spine BMD T-score, and glucocorticoid dose within each subpopulation.

Bone Histology

Bone biopsy specimens were obtained from 17 patients (11 in the active-control treatment group and 6 in the Prolia treatment group) at Month 12. Of the biopsies obtained, 17 (100%) were adequate for qualitative histology. Qualitative assessments showed bone of normal architecture and quality without mineralization defects or bone marrow abnormality. The presence of double tetracycline labeling in a biopsy specimen provides an indication of active bone remodeling, while the absence of tetracycline label suggests suppressed bone formation. In patients treated with active-control, 100% of biopsies had tetracycline label. In patients treated with Prolia, 1 (33%) had tetracycline label and 2 (67%) had no tetracycline label present at the 12-month biopsy. Evaluation of full quantitative histomorphometry including bone remodeling rates was not possible in the glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis population treated with Prolia. The long-term consequences of this degree of suppression of bone remodeling in glucocorticoid-treated patients is unknown.

14.4 Treatment of Bone Loss in Men with Prostate Cancer

The efficacy and safety of Prolia in the treatment of bone loss in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were demonstrated in a 3-year, randomized (1:1), double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study. Men less than 70 years of age had either a BMD T-score at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck between -1.0 and -4.0, or a history of an osteoporotic fracture. The mean baseline lumbar spine BMD T-score was -0.4, and 22% of men had a vertebral fracture at baseline. The 1468 men enrolled ranged in age from 48 to 97 years (median 76 years). Men were randomized to receive subcutaneous injections of either placebo (n = 734) or Prolia 60 mg (n = 734) once every 6 months for a total of 6 doses. Randomization was stratified by age (< 70 years vs. ≥ 70 years) and duration of ADT at trial entry (≤ 6 months vs. > 6 months). Seventy-nine percent of patients received ADT for more than 6 months at study entry. All men received at least 1000 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D supplementation daily.

Effect on Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

The primary efficacy variable was percent change in lumbar spine BMD from baseline to month 24. An additional key secondary efficacy variable was the incidence of new vertebral fracture through month 36 diagnosed based on x-ray evaluation by two independent radiologists. Lumbar spine BMD was higher at 2 years in Prolia-treated patients as compared to placebo-treated patients [-1.0% placebo, +5.6% Prolia; treatment difference 6.7% (95% CI: 6.2, 7.1); p < 0.0001].

With approximately 62% of patients followed for 3 years, treatment differences in BMD at 3 years were 7.9% (-1.2% placebo, +6.8% Prolia) at the lumbar spine, 5.7% (-2.6% placebo, +3.2% Prolia) at the total hip, and 4.9% (-1.8% placebo, +3.0% Prolia) at the femoral neck. Consistent effects on BMD were observed at the lumbar spine in relevant subgroups defined by baseline age, BMD, and baseline history of vertebral fracture.

Effect on Vertebral Fractures

Prolia significantly reduced the incidence of new vertebral fractures at 3 years (p = 0.0125), as shown in Table 5.

| Proportion of Men with Fracture (%)* | Absolute Risk Reduction (%)†

(95% CI) | Relative Risk Reduction (%)†

(95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo N = 673 (%) | Prolia N = 679 (%) |

|||

| 0-1 Year | 1.9 | 0.3 | 1.6 (0.5, 2.8) | 85 (33, 97) |

| 0-2 Years | 3.3 | 1.0 | 2.2 (0.7, 3.8) | 69 (27, 86) |

| 0-3 Years | 3.9 | 1.5 | 2.4 (0.7, 4.1) | 62 (22, 81) |

14.5 Treatment of Bone Loss in Women with Breast Cancer

The efficacy and safety of Prolia in the treatment of bone loss in women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy for breast cancer was assessed in a 2-year, randomized (1:1), double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study. Women had baseline BMD T-scores between -1.0 to -2.5 at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck, and had not experienced fracture after age 25. The mean baseline lumbar spine BMD T-score was -1.1, and 2.0% of women had a vertebral fracture at baseline. The 252 women enrolled ranged in age from 35 to 84 years (median 59 years). Women were randomized to receive subcutaneous injections of either placebo (n = 125) or Prolia 60 mg (n = 127) once every 6 months for a total of 4 doses. Randomization was stratified by duration of adjuvant AI therapy at trial entry (≤ 6 months vs. > 6 months). Sixty-two percent of patients received adjuvant AI therapy for more than 6 months at study entry. All women received at least 1000 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D supplementation daily.

Effect on Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

The primary efficacy variable was percent change in lumbar spine BMD from baseline to month 12. Lumbar spine BMD was higher at 12 months in Prolia-treated patients as compared to placebo-treated patients [-0.7% placebo, +4.8% Prolia; treatment difference 5.5% (95% CI: 4.8, 6.3); p < 0.0001].

With approximately 81% of patients followed for 2 years, treatment differences in BMD at 2 years were 7.6% (-1.4% placebo, +6.2% Prolia) at the lumbar spine, 4.7% (-1.0% placebo, +3.8% Prolia) at the total hip, and 3.6% (-0.8% placebo, +2.8% Prolia) at the femoral neck.

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

How Supplied

Prolia injection is a clear, colorless to pale yellow solution supplied in a single-dose prefilled syringe with a safety guard. The prefilled syringe is not made with natural rubber latex.

| 60 mg/mL in a single-dose prefilled syringe | 1 per carton | NDC 55513-710-01 NDC 55513-710-21 |

Storage and Handling

Store Prolia in a refrigerator at 2°C to 8°C (36°F to 46°F) in the original carton. Do not freeze. Prior to administration, Prolia may be allowed to reach room temperature (up to 25°C/77°F) in the original container. Once removed from the refrigerator, Prolia must not be exposed to temperatures above 25°C/77°F and must be used within 14 days. If not used within the 14 days, Prolia should be discarded. Do not use Prolia after the expiry date printed on the label. Protect Prolia from direct light and heat.

Avoid vigorous shaking of Prolia.

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Advise the patient to read the FDA-approved patient labeling (Medication Guide).

Hypocalcemia

Advise the patient to adequately supplement with calcium and vitamin D and instruct them on the importance of maintaining serum calcium levels while receiving Prolia [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1), Use in Specific Populations (8.6)]. Advise patients to seek prompt medical attention if they develop signs or symptoms of hypocalcemia.

Severe Hypocalcemia in Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease

Advise patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, including those who are dialysis-dependent, about the symptoms of hypocalcemia and the importance of maintaining serum calcium levels with adequate calcium and activated vitamin D supplementation. Advise these patients to have their serum calcium measured weekly for the first month after Prolia administration and monthly thereafter [see Dosage and Administration (2.2), Warnings and Precautions (5.1), Use in Specific Populations (8.6)]

Drug Products with Same Active Ingredient

Advise patients that denosumab is also marketed as Xgeva, and if taking Prolia, they should not receive Xgeva [see Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

Hypersensitivity

Advise patients to seek prompt medical attention if signs or symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions occur. Advise patients who have had signs or symptoms of systemic hypersensitivity reactions that they should not receive denosumab (Prolia or Xgeva) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), Contraindications (4)].

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

Advise patients to maintain good oral hygiene during treatment with Prolia and to inform their dentist prior to dental procedures that they are receiving Prolia. Patients should inform their physician or dentist if they experience persistent pain and/or slow healing of the mouth or jaw after dental surgery [see Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

Atypical Subtrochanteric and Diaphyseal Femoral Fractures

Advise patients to report new or unusual thigh, hip, or groin pain [see Warnings and Precautions (5.5)].

Multiple Vertebral Fractures (MVF) Following Discontinuation of Prolia Treatment

Advise patients not to interrupt Prolia therapy without talking to their physician [see Warnings and Precautions (5.6)].

Serious Infections

Advise patients to seek prompt medical attention if they develop signs or symptoms of infections, including cellulitis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.7)].

Dermatologic Adverse Reactions

Advise patients to seek prompt medical attention if they develop signs or symptoms of dermatological reactions (such as dermatitis, rashes, and eczema) [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

Musculoskeletal Pain

Inform patients that severe bone, joint, and/or muscle pain have been reported in patients taking Prolia. Patients should report severe symptoms if they develop [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)].

Pregnancy/Nursing

Counsel females of reproductive potential to use effective contraceptive measure to prevent pregnancy during treatment and for at least 5 months after the last dose of Prolia. Advise the patient to contact their physician immediately if pregnancy does occur during these times. Advise patients not to take Prolia while pregnant or breastfeeding. If a patient wishes to start breastfeeding after treatment, advise her to discuss the appropriate timing with her physician [see Contraindications (4), Use in Specific Populations (8.1)].

Prolia® (denosumab)

Manufactured by:

Amgen Inc.

One Amgen Center Drive

Thousand Oaks, California 91320-1799

U.S. License No. 1080

Patent: http://pat.amgen.com/prolia/

© 2010-2024 Amgen Inc. All rights reserved.

1xxxxxx – v26

| This Medication Guide has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. | Revised: 01/2024 | ||

| Medication Guide Prolia® (PRÓ-lee-a) (denosumab) Injection, for subcutaneous use |

|||

| What is the most important information I should know about Prolia?

If you receive Prolia, you should not receive XGEVA®. Prolia contains the same medicine as Xgeva (denosumab). Prolia can cause serious side effects including:

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|||

| What is Prolia?

Prolia is a prescription medicine used to:

|

|||

Do not take Prolia if you:

|

|||

Before taking Prolia, tell your doctor about all of your medical conditions, including if you:

Know the medicines you take. Keep a list of medicines with you to show to your doctor or pharmacist when you get a new medicine. |

|||

How will I receive Prolia?

|

|||

| What are the possible side effects of Prolia?

Prolia may cause serious side effects.

|

|||

|

|

||

| The most common side effects of Prolia in men with osteoporosis are: | |||

|

|

||

| The most common side effects of Prolia in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis are: | |||

|

|

||

| The most common side effects of Prolia in patients receiving certain treatments for prostate or breast cancer are: | |||

|

|

||

| Tell your doctor if you have any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away. These are not all the possible side effects of Prolia. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088. |

|||

How should I store Prolia if I need to pick it up from a pharmacy?

|

|||

| General information about the safe and effective use of Prolia.

Medicines are sometimes prescribed for purposes other than those listed in a Medication Guide. Do not use Prolia for a condition for which it was not prescribed. Do not give Prolia to other people, even if they have the same symptoms that you have. It may harm them. You can ask your doctor or pharmacist for information about Prolia that is written for health professionals. |

|||

| What are the ingredients in Prolia? Active ingredient: denosumab Inactive ingredients: sorbitol, acetate, polysorbate 20, Water for Injection (USP), and sodium hydroxide Amgen Inc. One Amgen Center Drive Thousand Oaks, California 91320-1799 1xxxxxx – v17 For more information, go to www.Prolia.com or call Amgen at 1-800-772-6436. |

|||

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 60 mg/mL Syringe Carton

1 x 60 mg Single-Dose Prefilled Syringe

NDC 55513-710-01

AMGEN®

prolia®

(denosumab)

60

mg/mL

60 mg/mL

Injection – For Subcutaneous Use Only.

Single-dose Prefilled Syringe. Discard unused portion.

Sterile Solution – No Preservative.

Rx Only

Refrigerate at 2° to 8°C (36° to 46°F). Do not freeze. Avoid excessive shaking. Protect from direct light and heat.

Manufactured by: Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA 91320-1799

Product of Singapore

PRINCIPAL DISPLAY PANEL - 60 mg/mL Syringe Carton

1 x 60 mg Single-Dose Prefilled Syringe

NDC 55513-710-21

AMGEN®

prolia®

(denosumab)

60

mg/mL

60 mg/mL

Injection – For Subcutaneous Use Only.

Single-dose Prefilled Syringe. Discard unused portion.

Sterile Solution – No Preservative.

Rx Only

Refrigerate at 2° to 8°C (36° to 46°F). Do not freeze. Avoid excessive shaking. Protect from direct light and heat.

Manufactured by: Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA 91320-1799

Product of Singapore