FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS

Antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in pediatric and young adult patients in short-term studies. Closely monitor all antidepressant-treated patients for clinical worsening, and for emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors [See Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Sertraline tablets are indicated for the treatment of the following [See Clinical Studies (14)]:

- Major depressive disorder (MDD)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Panic disorder (PD)

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Social anxiety disorder (SAD)

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD)

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Dosage in Patients with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, and SAD

The recommended initial dosage and maximum sertraline dosage in patients with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, and SAD are displayed in Table 1 below. A dosage of 25 mg or 50 mg per day is the initial therapeutic dosage.

For adults and pediatric patients, subsequent dosages may be increased in case of an inadequate response in 25 mg to 50 mg per day increments once a week, depending on tolerability, up to a maximum of 200 mg per day. Given the 24-hour elimination half-life of sertraline, the recommended interval between dose changes is one week.

| Table 1: Recommended Daily Dosage of Sertraline in Patients with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, and SAD

|

||

| Indication

| Starting Dose

| Therapeutic Range

|

| Adults

|

||

| MDD | 50 mg | 50 to 200 mg |

| OCD | 50 mg |

|

| PD, PTSD, SAD | 25 mg |

|

| Pediatric Patients

|

||

| OCD (ages 6-12 years old) | 25 mg | 50 to 200 mg |

| OCD (ages 13-17 years old) | 50 mg |

|

2.2 Dosage in Patients with PMDD

The recommended starting sertraline dosage in adult women with PMDD is 50 mg per day. Sertraline may be administered either continuously (every day throughout the menstrual cycle) or intermittently (only during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, i.e., starting the daily dosage 14 days prior to the anticipated onset of menstruation and continuing through the onset of menses). Intermittent dosing would be repeated with each new cycle.

- When dosing continuously, patients not responding to a 50 mg dosage may benefit from dosage increases at 50 mg increments per menstrual cycle up to 150 mg per day.

- When dosing intermittently, patients not responding to a 50 mg dosage may benefit from increasing the dosage up to a maximum of 100 mg per day during the next menstrual cycle (and subsequent cycles) as follows: 50 mg per day during the first 3 days of dosing followed by 100 mg per day during the remaining days in the dosing cycle.

2.3 Screen for Bipolar Disorder Prior to Starting Sertraline

Prior to initiating treatment with sertraline or another antidepressant, screen patients for a personal or family history of bipolar disorder, mania, or hypomania [See Warnings and Precautions (5.4)].

2.4 Dosage Modifications in Patients with Hepatic Impairment

Both the recommended starting dosage and therapeutic range in patients with mild hepatic impairment (Child Pugh scores 5 or 6) are half the recommended daily dosage [See Dosage and Administration (2.1, 2.2)]. The use of sertraline in patients with moderate (Child Pugh scores 7 to 9) or severe hepatic impairment (Child Pugh scores 10-15) is not recommended [See Use in Specific Populations (8.6), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

2.5 Switching Patients to or from a Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor Antidepressant

At least 14 days must elapse between discontinuation of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) antidepressant and initiation of sertraline. In addition, at least 14 days must elapse after stopping sertraline before starting an MAOI antidepressant [See Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

2.6 Discontinuation of Treatment with Sertraline

Adverse reactions may occur upon discontinuation of sertraline [See Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]. Gradually reduce the dosage rather than stopping sertraline abruptly whenever possible.

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Sertraline 25 mg Tablets: Light Green film coated Modified oval biconvex tablets debossed with I on the left Side of bisect and G on the right Side of bisect on one Side and “212” on other

Sertraline 50 mg Tablets: Light Blue film coated Modified oval biconvex tablets debossed with I on the left side of bisect and G on the right side of bisect on one side and “213” on other

Sertraline 100 mg Tablets: Light Yellow film coated Modified oval biconvex tablets debossed with I on the left side of bisect and G on the right side of bisect on one side and “214” on other

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

Sertraline is contraindicated in patients:

- Taking, or within 14 days of stopping, MAOIs, (including the MAOIs linezolid and intravenous methylene blue) because of an increased risk of serotonin syndrome [See Warnings and Precautions (5.2), Drug Interactions (7.1)].

- Taking pimozide [See Drug Interactions (7.1)].

- With known hypersensitivity to sertraline (e.g., anaphylaxis, angioedema) [See Adverse Reactions (6.1, 6.2)].

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients

In pooled analyses of placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drugs (SSRIs and other antidepressant classes) that included approximately 77,000 adult patients and over 4,400 pediatric patients, the incidence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in pediatric and young adult patients was greater in antidepressant-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients. The drug-placebo differences in the number of cases of suicidal thoughts and behaviors per 1,000 patients treated are provided in Table 2.

No suicides occurred in any of the pediatric studies. There were suicides in the adult studies, but the number was not sufficient to reach any conclusion about antidepressant drug effect on suicide.

Table 2: Risk Differences of the Number of Cases of Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors in the Pooled Placebo-Controlled Trials of Antidepressants in Pediatric and Adult Patients

| Age Range (years)

| Drug-Placebo Difference in Number of Patients of Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors per 1000 Patients Treated

|

| Increases Compared to Placebo

|

|

| <18 | 14 additional patients |

| 18-24 | 5 additional patients |

| Decreases Compared to Placebo

|

|

| 25-64 | 1 fewer patient |

| ≥65 | 6 fewer patients |

It is unknown whether the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in pediatric and young adult patients extends to longer-term use, i.e., beyond four months. However, there is substantial evidence from placebo-controlled maintenance trials in adults with MDD that antidepressants delay the recurrence of depression.

Monitor all antidepressant-treated patients for clinical worsening and emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, especially during the initial few months of drug therapy and at times of dosage changes. Counsel family members or caregivers of patients to monitor for changes in behavior and to alert the healthcare provider. Consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including possibly discontinuing sertraline, in patients whose depression is persistently worse, or who are experiencing emergent suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

5.2 Serotonin Syndrome

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and SSRIs, including sertraline, can precipitate serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition. The risk is increased with concomitant use of other serotonergic drugs (including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, amphetamines, and St. John’s Wort) and with drugs that impair metabolism of serotonin, i.e., MAOIs [See Contraindications (4), Drug Interactions (7.1)]. Serotonin syndrome can also occur when these drugs are used alone.

Serotonin syndrome signs and symptoms may include mental status changes (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, delirium, and coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, dizziness, diaphoresis, flushing, hyperthermia), neuromuscular symptoms (e.g., tremor, rigidity, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, incoordination), seizures, and gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea).

The concomitant use of sertraline with MAOIs is contraindicated. In addition, do not initiate sertraline in a patient being treated with MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue. No reports involved the administration of methylene blue by other routes (such as oral tablets or local tissue injection). If it is necessary to initiate treatment with an MAOI such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue in a patient taking sertraline, discontinue sertraline before initiating treatment with the MAOI [See Contraindications (4), Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Monitor all patients taking sertraline for the emergence of serotonin syndrome. Discontinue treatment with sertraline and any concomitant serotonergic agents immediately if the above symptoms occur, and initiate supportive symptomatic treatment. If concomitant use of sertraline with other serotonergic drugs is clinically warranted, inform patients of the increased risk for serotonin syndrome and monitor for symptoms.

5.3 Increased Risk of Bleeding

Drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake inhibition, including sertraline, increase the risk of bleeding events. Concomitant use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other antiplatelet drugs, warfarin, and other anticoagulants may add to this risk. Case reports and epidemiological studies (case-control and cohort design) have demonstrated an association between use of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding events related to drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake have ranged from ecchymosis, hematoma, epistaxis, and petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages.

Inform patients of the increased risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of sertraline and antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants. For patients taking warfarin, carefully monitor the international normalized ratio.

5.4 Activation of Mania or Hypomania

In patients with bipolar disorder, treating a depressive episode with sertraline or another antidepressant may precipitate a mixed/manic episode. In controlled clinical trials, patients with bipolar disorder were generally excluded; however, symptoms of mania or hypomania were reported in 0.4% of patients treated with sertraline. Prior to initiating treatment with sertraline, screen patients for any personal or family history of bipolar disorder, mania, or hypomania.

5.5 Discontinuation Syndrome

Adverse reactions after discontinuation of serotonergic antidepressants, particularly after abrupt discontinuation, include: nausea, sweating, dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesia, such as electric shock sensations), tremor, anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, hypomania, tinnitus, and seizures. A gradual reduction in dosage rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible [See Dosage and Administration (2.6)].

5.6 Seizures

Sertraline has not been systematically evaluated in patients with seizure disorders. Patients with a history of seizures were excluded from clinical studies. Sertraline should be prescribed with caution in patients with a seizure disorder.

5.7 Angle-Closure Glaucoma

The pupillary dilation that occurs following use of many antidepressant drugs including sertraline may trigger an angle closure attack in a patient with anatomically narrow angles who does not have a patent iridectomy. Avoid use of antidepressants, including sertraline, in patients with untreated anatomically narrow angles.

5.8 Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia may occur as a result of treatment with SNRIs and SSRIs, including sertraline. Cases with serum sodium lower than 110 mmol/L have been reported. Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia include headache, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, confusion, weakness, and unsteadiness, which may lead to falls. Signs and symptoms associated with more severe or acute cases have included hallucination, syncope, seizure, coma, respiratory arrest, and death. In many cases, this hyponatremia appears to be the result of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH).

In patients with symptomatic hyponatremia, discontinue sertraline and institute appropriate medical intervention. Elderly patients, patients taking diuretics, and those who are volume-depleted may be at greater risk of developing hyponatremia with SSRIs and SNRIs [See Use in Specific Populations (8.5)].

5.9 False-Positive Effects on Screening Tests for Benzodiazepines

False-positive urine immunoassay screening tests for benzodiazepines have been reported in patients taking sertraline. This finding is due to lack of specificity of the screening tests. False-positive test results may be expected for several days following discontinuation of sertraline. Confirmatory tests, such as gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, will help distinguish sertraline from benzodiazepines [See Drug Interactions (7.3)].

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

The following adverse reactions are described in more detail in other sections of the prescribing information:

- Hypersensitivity reactions to sertraline [See Contraindications (4)]

- QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias when taken with pimozide [See Contraindications (4)]

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors [See Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]

- Serotonin syndrome [See Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.2), Drug Interactions (7.1)]

- Increased risk of bleeding [See Warnings and Precautions (5.3)]

- Activation of mania/hypomania [See Warnings and Precautions (5.4)]

- Discontinuation syndrome [See Warnings and Precautions (5.5)]

- Seizures [See Warnings and Precautions (5.6)]

- Angle-closure glaucoma [See Warnings and Precautions (5.7)]

- Hyponatremia [See Warnings and Precautions (5.8)]

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

The data described below are from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of sertraline (mostly 50 mg to 200 mg per day) in 3,066 adults diagnosed with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD, and PMDD. These 3,066 patients exposed to sertraline for 8 to12 weeks represent 568 patient-years of exposure. The mean age was 40 years; 57% were females and 43% were males.

The most common adverse reactions (≥5% and twice placebo) in all pooled placebo-controlled clinical trials of all sertraline -treated patients with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD and PMDD were nausea, diarrhea/loose stool, tremor, dyspepsia, decreased appetite, hyperhidrosis, ejaculation failure, and decreased libido (see Table 3). The following are the most common adverse reactions in trials of sertraline (≥5% and twice placebo) by indication that were not mentioned previously.

- MDD: somnolence;

- OCD: insomnia, agitation;

- PD: constipation, agitation;

- PTSD: fatigue;

- PMDD: somnolence, dry mouth, dizziness, fatigue, and abdominal pain;

- SAD: insomnia, dizziness, fatigue, dry mouth, malaise.

Table 3: Common Adverse Reactions in Pooled Placebo-Controlled Trials in Adults with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD, and PMDD*

| | Sertraline (N=3066)

| Placebo

(N=2293) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac disorders

| | |

| Palpitations | 4% | 2% |

| Eye disorders

| | |

| Visual impairment | 4% | 2% |

| Gastrointestinal Disorders

| | |

| Nausea | 26% | 12% |

| Diarrhea/Loose Stools | 20% | 10% |

| Dry mouth | 14% | 9% |

| Dyspepsia | 8% | 4% |

| Constipation | 6% | 4% |

| Vomiting | 4% | 1% |

| General disorders and administration site conditions

| | |

| Fatigue | 12% | 8% |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders

| | |

| Decreased appetite | 7% | 2% |

| Nervous system disorders

| | |

| Dizziness | 12% | 8% |

| Somnolence | 11% | 6% |

| Tremor | 9% | 2% |

| Psychiatric Disorders

| | |

| Insomnia | 20% | 13% |

| Agitation | 8% | 5% |

| Libido Decreased | 6% | 2% |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders

| | |

| Ejaculation failure (1)

| 8% | 1% |

| Erectile dysfunction (1)

| 4% | 1% |

| Ejaculation disorder (1)

| 3% | 0% |

| Male sexual dysfunction (1)

| 2% | 0% |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders

| | |

| Hyperhidrosis | 7% | 3% |

(1) Denominator used was for male patients only (n=1316 sertraline; n=973 placebo).

* Adverse reactions that occurred greater than 2% in sertraline -treated patients and at least 2% greater in sertraline -treated patients than placebo-treated patients.

Adverse Reactions Leading to Discontinuation in Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials

In all placebo-controlled studies in patients with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD and PMDD, 368 (12%) of the 3,066 patients who received sertraline discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with 93 (4%) of the 2,293 placebo-treated patients. In placebo-controlled studies, the following were the common adverse reactions leading to discontinuation in sertraline -treated patients:

- MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD and PMDD: nausea (3%), diarrhea (2%), agitation (2%), and insomnia (2%).

- MDD (>2% and twice placebo): decreased appetite, dizziness, fatigue, headache, somnolence, tremor, and vomiting.

- OCD: somnolence.

- PD: nervousness and somnolence.

Male and Female Sexual Dysfunction

Although changes in sexual desire, sexual performance and sexual satisfaction often occur as manifestations of a psychiatric disorder, they may also be a consequence of SSRI treatment. However, reliable estimates of the incidence and severity of untoward experiences involving sexual desire, performance and satisfaction are difficult to obtain, in part because patients and healthcare providers may be reluctant to discuss them. Accordingly, estimates of the incidence of untoward sexual experience and performance cited in labeling may underestimate their actual incidence.

Table 4 below displays the incidence of sexual adverse reactions reported by at least 2% of sertraline-treated patients and twice placebo from pooled placebo-controlled trials. For men and all indications, the most common adverse reactions (>2% and twice placebo) included: ejaculation failure, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, ejaculation disorder, and male sexual dysfunction. For women, the most common adverse reaction (≥2% and twice placebo) was decreased libido.

Table 4: Most Common Sexual Adverse Reactions (≥2% and twice placebo) in Men or Women from Sertraline Pooled Controlled Trials in Adults with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD, and PMDD

| | Sertraline

| Placebo

|

| Men only

| (N=1316)

| (N=973)

|

| Ejaculation failure | 8% | 1% |

| Libido decreased | 7% | 2% |

| Erectile dysfunction | 4% | 1% |

| Ejaculation disorder | 3% | 0% |

| Male sexual dysfunction | 2% | 0% |

| Women only

| (N=1750)

| (N=1320)

|

| Libido decreased | 4% | 2% |

Adverse Reactions in Pediatric Patients

In 281 pediatric patients treated with sertraline in placebo-controlled studies, the overall profile of adverse reactions was generally similar to that seen in adult studies. Adverse reactions that do not appear in Table 3 (most common adverse reactions in adults) yet were reported in at least 2% of pediatric patients and at a rate of at least twice the placebo rate include fever, hyperkinesia, urinary incontinence, aggression, epistaxis, purpura, arthralgia, decreased weight, muscle twitching, and anxiety.

Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Premarketing Evaluation of Sertraline

Other infrequent adverse reactions, not described elsewhere in the prescribing information, occurring at an incidence of < 2% in patients treated with sertraline were:

Cardiac disorders – tachycardia

Ear and labyrinth disorders – tinnitus

Endocrine disorders - hypothyroidism

Eye disorders -mydriasis, blurred vision

Gastrointestinal disorders - hematochezia, melena, rectal hemorrhage

General disorders and administration site conditions - edema, gait disturbance, irritability, pyrexia

Hepatobiliary disorders - elevated liver enzymes

Immune system disorders - anaphylaxis

Metabolism and nutrition disorders - diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, hypoglycemia, increased appetite

Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders – arthralgia, muscle spasms, tightness, or twitching

Nervous system disorders - ataxia, coma, convulsion, decreased alertness, hypoesthesia, lethargy, psychomotor hyperactivity, syncope

Psychiatric disorders - aggression, bruxism, confusional state, euphoric mood, hallucination

Renal and urinary disorders - hematuria

Reproductive system and breast disorders - galactorrhea, priapism, vaginal hemorrhage

Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders - bronchospasm, epistaxis, yawning

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders - alopecia; cold sweat; dermatitis; dermatitis bullous; pruritus; purpura; erythematous, follicular, or maculopapular rash; urticaria

Vascular disorders - hemorrhage, hypertension, vasodilation

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of sertraline. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Bleeding or clotting disorders - increased coagulation times (altered platelet function)

Cardiac disorders – AV block, bradycardia, atrial arrhythmias, QT-interval prolongation, ventricular tachycardia (including Torsade de Pointes)

Endocrine disorders -gynecomastia, hyperprolactinemia, menstrual irregularities, SIADH

Eye disorders - blindness, optic neuritis, cataract

Hepatobiliary disorders – severe liver events (including hepatitis, jaundice, liver failure with some fatal outcomes), pancreatitis

Hemic and Lymphatic – agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia and pancytopenia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, lupus-like syndrome, serum sickness

Immune system disorders - angioedema

Metabolism and nutrition disorders – hyponatremia, hyperglycemia

Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders - trismus

Nervous system disorders -serotonin syndrome, extrapyramidal symptoms (including akathisia and dystonia), oculogyric crisis

Psychiatric disorders – psychosis, enuresis, paroniria

Renal and urinary disorders - acute renal failure

Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal

disorders - pulmonary hypertension

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders - photosensitivity skin reaction and other severe cutaneous reactions, which potentially can be fatal, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

Vascular disorders - cerebrovascular spasm (including reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and Call-Fleming syndrome), vasculitis

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

7.1 Clinically Significant Drug Interactions

Table 5 includes clinically significant drug interactions with sertraline [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

Table 5: Clinically-Significant Drug Interactions with Sertraline

| Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs)

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| The concomitant use of SSRIs including sertraline and MAOIs increases the risk of serotonin syndrome. |

| Intervention:

| Sertraline is contraindicated in patients taking MAOIs, including MAOIs such as linezolid or intravenous methylene blue [See Dosage and Administration (2.5), Contraindications (4), Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

|

| Examples:

| selegiline, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, phenelzine, linezolid, methylene blue |

| Pimozide

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| Increased plasma concentrations of pimozide, a drug with a narrow therapeutic index, may increase the risk of QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias. |

| Intervention:

| Concomitant use of pimozide and sertraline is contraindicated [See Contraindications (4)].

|

| Other Serotonergic Drugs

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| The concomitant use of serotonergic drugs with sertraline increases the risk of serotonin syndrome. |

| Intervention:

| Monitor patients for signs and symptoms of serotonin syndrome, particularly during treatment initiation and dosage increases. If serotonin syndrome occurs, consider discontinuation of sertraline and/or concomitant serotonergic drugs [See Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

|

| Examples:

| other SSRIs, SNRIs, triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, St. John’s Wort |

| Drugs that Interfere with Hemostasis (antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants)

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| The concurrent use of an antiplatelet agent or anticoagulant with sertraline may potentiate the risk of bleeding. |

| Intervention:

| Inform patients of the increased risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of sertraline and antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants. For patients taking warfarin, carefully monitor the international normalized ratio [See Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

|

| Examples:

| aspirin, clopidogrel, heparin, warfarin |

| Drugs Highly Bound to Plasma Protein

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| Sertraline is highly bound to plasma protein. The concomitant use of sertraline with another drug that is highly bound to plasma protein may increase free concentrations of sertraline or other tightly-bound drugs in plasma [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. |

| Intervention:

| Monitor for adverse reactions and reduce dosage of sertraline or other protein-bound drugs as warranted. |

| Examples:

| warfarin |

| Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| Sertraline is a CYP2D6 inhibitor [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)]. The concomitant use of sertraline with a CYP2D6 substrate may increase the exposure of the CYP2D6 substrate. |

| Intervention:

| Decrease the dosage of a CYP2D6 substrate if needed with concomitant sertraline use. Conversely, an increase in dosage of a CYP2D6 substrate may be needed if sertraline is discontinued. |

| Examples:

| propafenone, flecainide, atomoxetine, desipramine, dextromethorphan, metoprolol, nebivolol, perphenazine, thoridazine, tolterodine, venlafaxine |

| Phenytoin

|

|

| Clinical Impact:

| Phenytoin is a narrow therapeutic index drug. Sertraline may increase phenytoin concentrations. |

| Intervention:

| Monitor phenytoin levels when initiating or titrating sertraline. Reduce phenytoin dosage if needed. |

| Examples:

| phenytoin, fosphenytoin |

7.2 Drugs Having No Clinically Important Interactions with Sertraline

Based on pharmacokinetic studies, no dosage adjustment of sertraline is necessary when used in combination with cimetidine. Additionally, no dosage adjustment is required for diazepam, lithium, atenolol, tolbutamide, digoxin, and drugs metabolized by CYP3A4, when sertraline is administered concomitantly [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

7.3 False-Positive Screening Tests for Benzodiazepines

False-positive urine immunoassay screening tests for benzodiazepines have been reported in patients taking sertraline. This finding is due to lack of specificity of the screening tests. False-positive test results may be expected for several days following discontinuation of sertraline. Confirmatory tests, such as gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, will distinguish sertraline from benzodiazepines.

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Risk Summary

Overall, available published epidemiologic studies of pregnant women exposed to sertraline in the first trimester suggest no difference in major birth defect risk compared to the background rate for major birth defects in comparator populations. Some studies have reported increases for specific major birth defects; however, these study results are inconclusive [See Data]. There are clinical considerations regarding neonates exposed to SSRIs and SNRIs, including sertraline, during the third trimester of pregnancy [See Clinical Considerations].

Although no teratogenicity was observed in animal reproduction studies, delayed fetal ossification was observed when sertraline was administered during the period of organogenesis at doses less than the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) in rats and doses 3.1 times the MRHD in rabbits on a mg/m2 basis in adolescents. When sertraline was administered to female rats during the last third of gestation, there was an increase in the number of stillborn pups and pup deaths during the first four days after birth at the MRHD [See Data].

The background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated population are unknown. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2 to 4% and 15 to 20%, respectively. Advise a pregnant woman of possible risks to the fetus when prescribing sertraline.

Clinical Considerations

Disease-associated maternal and/or embryo/fetal risk

A prospective longitudinal study followed 201 pregnant women with a history of major depression who were euthymic taking antidepressants at the beginning of pregnancy. The women who discontinued antidepressants during pregnancy were more likely to experience a relapse of major depression than women who continued antidepressants. Consider the risks of untreated depression when discontinuing or changing treatment with antidepressant medication during pregnancy and postpartum.

Fetal/Neonatal adverse reactions

Exposure to SSRIs and SNRIs, including sertraline in late pregnancy may lead to an increased risk for neonatal complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding, and/or persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN).

When treating a pregnant woman with sertraline during the third trimester, carefully consider both the potential risks and benefits of treatment. Monitor neonates who were exposed to sertraline in the third trimester of pregnancy for PPHN and drug discontinuation syndrome [See Data].

Data

Human Data

Third Trimester Exposure

Neonates exposed to sertraline and other SSRIs or SNRIs late in the third trimester have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding. These findings are based on post-marketing reports. Such complications can arise immediately upon delivery. Reported clinical findings have included respiratory distress, cyanosis, apnea, seizures, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotonia, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, tremor, jitteriness, irritability, and constant crying. These features are consistent with either a direct toxic effect of SSRIs and SNRIs or, possibly, a drug discontinuation syndrome. In some cases, the clinical picture was consistent with serotonin syndrome [See Warnings and Precautions (5.2)].

Exposure during late pregnancy to SSRIs may have an increased risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). PPHN occurs in 1-2 per 1,000 live births in the general population and is associated with substantial neonatal morbidity and mortality. In a retrospective case-control study of 377 women whose infants were born with PPHN and 836 women whose infants were born healthy, the risk for developing PPHN was approximately six-fold higher for infants exposed to SSRIs after the 20th week of gestation compared to infants who had not been exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy. A study of 831,324 infants born in Sweden in 1997-2005 found a PPHN risk ratio of 2.4 (95% CI 1.2-4.3) associated with patient-reported maternal use of SSRIs “in early pregnancy” and a PPHN risk ratio of 3.6 (95% CI 1.2-8.3) associated with a combination of patient-reported maternal use of SSRIs “in early pregnancy” and an antenatal SSRI prescription “in later pregnancy”.

First Trimester Exposure

The weight of evidence from epidemiologic studies of pregnant women exposed to sertraline in the first trimester suggest no difference in major birth defect risk compared to the background rate for major birth defects in pregnant women who were not exposed to sertraline. A meta-analysis of studies suggest no increase in the risk of total malformations (summary odds ratio=1.01, 95% CI=0.88-1.17) or cardiac malformations (summary odds ratio=0.93, 95% CI=0.70-1.23) among offspring of women with first trimester exposure to sertraline. An increased risk of congenital cardiac defects, specifically septal defects, the most common type of congenital heart defect, was observed in some published epidemiologic studies with first trimester sertraline exposure; however, most of these studies were limited by the use of comparison populations that did not allow for the control of confounders such as the underlying depression and associated conditions and behaviors, which may be factors associated with increased risk of these malformations.

Animal Data

Reproduction studies have been performed in rats and rabbits at doses up to 80 mg/kg/day and 40 mg/kg/day, respectively. These doses correspond to approximately 3.1 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 200 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis in adolescents. There was no evidence of teratogenicity at any dose level. When pregnant rats and rabbits were given sertraline during the period of organogenesis, delayed ossification was observed in fetuses at doses of 10 mg/kg (0.4 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) in rats and 40 mg/kg (3.1 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) in rabbits. When female rats received sertraline during the last third of gestation and throughout lactation, there was an increase in stillborn pups and pup deaths during the first 4 days after birth. Pup body weights were also decreased during the first four days after birth. These effects occurred at a dose of 20 mg/kg (0.8 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis). The no effect dose for rat pup mortality was 10 mg/kg (0.4 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis). The decrease in pup survival was shown to be due to in utero exposure to sertraline. The clinical significance of these effects is unknown.

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

Available data from published literature demonstrate low levels of sertraline and its metabolites in human milk [See Data]. There are no data on the effects of sertraline on milk production. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for sertraline and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from the drug or from the underlying maternal condition.

Data

In a published pooled analysis of 53 mother-infant pairs, exclusively human milk-fed infants had an average of 2% (range 0% to 15%) of the sertraline serum levels measured in their mothers. No adverse reactions were observed in these infants.

8.4 Pediatric Use

The safety and efficacy of sertraline have been established in the treatment of OCD in pediatric patients aged 6 to 17 [See Adverse Reactions (6.1), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3), Clinical Studies (14.2)]. Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients in patients with OCD below the age of 6 have not been established. Safety and effectiveness have not been established in pediatric patients for indications other than OCD. Two placebo-controlled trials were conducted in pediatric patients with MDD, but the data were not sufficient to support an indication for use in pediatric patients.

Monitoring Pediatric Patients Treated with Sertraline

Monitor all patients being treated with antidepressants for clinical worsening, suicidal thoughts, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of treatment, or at times of dose increases or decreases [See Boxed Warning, Warnings and Precautions (5.1)]. Decreased appetite and weight loss have been observed with the use of SSRIs. Monitor weight and growth in pediatric patients treated with an SSRI such as sertraline.

Weight Loss in Studies in Pediatric Patients with MDD

In a pooled analysis of two 10-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible dose (50-200 mg) outpatient trials for MDD (n=373), there was a difference in weight change between sertraline and placebo of roughly 1 kg, for both children (ages 6-11) and adolescents (ages 12-17), in both age groups representing a slight weight loss for the sertraline group compared to a slight gain for the placebo group. For children, about 7% of the sertraline -treated patients had a weight loss greater than 7% of body weight compared to 0% of the placebo-treated patients; for adolescents, about 2% of sertraline -treated patients had a weight loss > 7% of body weight compared to about 1% of placebo-treated patients.

A subset of patients who completed the randomized controlled trials in patients with MDD (sertraline n=99, placebo n=122) were continued into a 24-week, flexible-dose, open-label, extension study. Those subjects who completed 34 weeks of sertraline treatment (10 weeks in a placebo-controlled trial + 24 weeks open-label, n=68) had weight gain that was similar to that expected using data from age-adjusted peers. However, there are no studies that directly evaluate the long-term effects of sertraline on the growth, development, and maturation in pediatric patients.

Juvenile Animal Data

A study conducted in juvenile rats at clinically relevant doses showed delay in sexual maturation, but there was no effect on fertility in either males or females.

In this study in which juvenile rats were treated with oral doses of sertraline at 0, 10, 40 or 80 mg/kg/day from postnatal day 21 to 56, a delay in sexual maturation was observed in males treated with 80 mg/kg/day and females treated with doses ≥10 mg/kg/day. There was no effect on male and female reproductive endpoints or neurobehavioral development up to the highest dose tested (80 mg/kg/day), except a decrease in auditory startle response in females at 40 and 80 mg/kg/day at the end of treatment but not at the end of the drug –free period. The highest dose of 80 mg/kg/day produced plasma levels (AUC) of sertraline 5 times those seen in pediatric patients (6 – 17 years of age) receiving the maximum recommended dose of sertraline (200 mg/day).

8.5 Geriatric Use

Of the total number of patients in clinical studies of sertraline in patients with MDD, OCD, PD, PTSD, SAD and PMDD, 797 (17%) were ≥ 65 years old, while 197 (4%) were ≥ 75 years old.

No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between these subjects and younger subjects, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients. In general, dose selection for an elderly patient should be conservative, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.

In 354 geriatric subjects treated with sertraline in MDD placebo-controlled trials, the overall profile of adverse reactions was generally similar to that shown in Table 3[See Adverse Reactions (6.1)], except for tinnitus, arthralgia with an incidence of at least 2% and at a rate greater than placebo in geriatric patients.

SNRIs and SSRIs, including sertraline, have been associated with cases of clinically significant hyponatremia in elderly patients, who may be at greater risk for this adverse reaction [See Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

8.6 Hepatic Impairment

The recommended dosage in patients with mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score 5 or 6) is half the recommended dosage due to increased exposure in this patient population. The use of sertraline in patients with moderate (Child-Pugh score 7 to 10) or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score 10-15) is not recommended, because sertraline is extensively metabolized, and the effects of sertraline in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment have not been studied [See Dosage and Administration (2.4), Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

8.7 Renal Impairment

No dose adjustment is needed in patients with mild to severe renal impairment. Sertraline exposure does not appear to be affected by renal impairment [See Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)].

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.2 Abuse

In a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of the comparative abuse liability of sertraline, alprazolam, and d-amphetamine in humans, sertraline did not produce the positive subjective effects indicative of abuse potential, such as euphoria or drug liking, that were observed with the other two drugs.

10 OVERDOSAGE

Human Experience

The most common signs and symptoms associated with non-fatal sertraline overdosage were somnolence, vomiting, tachycardia, nausea, dizziness, agitation and tremor. No cases of fatal overdosage with only sertraline have been reported.

Other important adverse events reported with sertraline overdose (single or multiple drugs) include bradycardia, bundle branch block, coma, convulsions, delirium, hallucinations, hypertension, hypotension, manic reaction, pancreatitis, QT-interval prolongation, Torsade de Pointes, serotonin syndrome, stupor, and syncope.

Overdose Management

No specific antidotes for sertraline are known. Contact Poison Control (1-800-222-1222) for latest recommendations.

11 DESCRIPTION

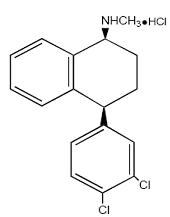

Sertraline contains sertraline hydrochloride, an SSRI. Sertraline hydrochloride has a molecular weight of 342.7 and has the following chemical name: (1S-cis)-4-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-N-methyl-1-naphthalenamine hydrochloride. The empirical formula C17H17NCl2•HCl is represented by the following structural formula:

Sertraline hydrochloride is a white crystalline powder that is slightly soluble in water and isopropyl alcohol, and sparingly soluble in ethanol.

Sertraline tablets, USP for oral administration are supplied as scored tablets containing sertraline hydrochloride equivalent to 25 mg, 50 mg and 100 mg of sertraline and the following inactive ingredients: dibasic calcium phosphate dihydrate, hydroxypropyl cellulose, microcrystalline cellulose, magnesium stearate, opadry green (titanium dioxide, hypromellose 3cP, hypromellose 6cP, Macrogol/Peg 400, polysorbate 80, D&C Yellow #10 Aluminum Lake, and FD&C Blue # 2/Indigo Carmine Aluminum Lake for 25 mg tablet), opadry light blue (hypromellose 3cP, hypromellose 6cP, titanium dioxide, Macrogol/Peg 400, FD&C Blue #2/Indigo Carmine Aluminum Lake and polysorbate 80 for 50 mg tablet), opadry yellow (hypromellose 3cP, hypromellose 6cP, titanium dioxide, Macrogol/Peg 400, polysorbate 80, Iron Oxide Yellow, Iron oxide Red for 100 mg tablet) and sodium starch glycolate.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

Sertraline potentiates serotonergic activity in the central nervous system through inhibition of neuronal reuptake of serotonin (5-HT).

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

Studies at clinically relevant doses have demonstrated that sertraline blocks the uptake of serotonin into human platelets. In vitro studies in animals also suggest that sertraline is a potent and selective inhibitor of neuronal serotonin reuptake and has only very weak effects on norepinephrine and dopamine neuronal reuptake. In vitro studies have shown that sertraline has no significant affinity for adrenergic (alpha1, alpha2, beta), cholinergic, GABA, dopaminergic, histaminergic, serotonergic (5HT1A, 5HT1B, 5HT2), or benzodiazepine receptors. The chronic administration of sertraline was found in animals to down regulate brain norepinephrine receptors. Sertraline does not inhibit monoamine oxidase.

Alcohol

In healthy subjects, the acute cognitive and psychomotor effects of alcohol were not potentiated by sertraline.

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Following oral once-daily sertraline dosing over the range of 50 to 200 mg for 14 days, mean peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of sertraline occurred between 4.5 to 8.4 hours post-dosing. The average terminal elimination half-life of plasma sertraline is about 26 hours. Consistent with the terminal elimination half-life, there is an approximately two-fold accumulation up to steady-state concentrations, which are achieved after one week of once- daily dosing. Linear dose-proportional pharmacokinetics were demonstrated in a single dose study in which the Cmax and area under the plasma concentration time curve (AUC) of sertraline were proportional to dose over a range of 50 to 200 mg. The single dose bioavailability of sertraline tablets is approximately equal to an equivalent dose of sertraline oral solution. Administration with food causes a small increase in Cmax and AUC.

Metabolism

Sertraline undergoes extensive first pass metabolism. The principal initial pathway of metabolism for sertraline is N-demethylation. N-desmethylsertraline has a plasma terminal elimination half-life of 62 to 104 hours. Both in vitro biochemical and in vivo pharmacological testing have shown N-desmethylsertraline to be substantially less active than sertraline. Both sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline undergo oxidative deamination and subsequent reduction, hydroxylation, and glucuronide conjugation. In a study of radiolabeled sertraline involving two healthy male subjects, sertraline accounted for less than 5% of the plasma radioactivity. About 40 to 45% of the administered radioactivity was recovered in urine in 9 days. Unchanged sertraline was not detectable in the urine. For the same period, about 40-45% of the administered radioactivity was accounted for in feces, including 12 to 14% unchanged sertraline.

Desmethylsertraline exhibits time-related, dose dependent increases in AUC (0-24-hour), Cmax and Cmin, with about a 5- to 9-fold increase in these pharmacokinetic parameters between day 1 and day 14.

Protein Binding

In vitro protein binding studies performed with radiolabeled 3H-sertraline showed that sertraline is highly bound to serum proteins (98%) in the range of 20 to 500 ng/mL. However, at up to 300 and 200 ng/mL concentrations, respectively, sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline did not alter the plasma protein binding of two other highly protein bound drugs, warfarin and propranolol.

Studies in Specific Populations

Pediatric Patients

Sertraline pharmacokinetics were evaluated in a group of 61 pediatric patients (29 aged 6 to12 years, 32 aged 13 to 17 years) including both males (N=28) and females (N=33). Relative to the adults, pediatric patients aged 6 to12 years and 13 to 17 years showed about 22% lower AUC (0 to 24 hr) and Cmax values when plasma concentration was adjusted for weight. The half-life was similar to that in adults, and no gender-associated differences were observed [See Dosage and Administration (2.1), Use in Specific Populations (8.4)].

Geriatric Patients

Sertraline plasma clearance in a group of 16 (8 male, 8 female) elderly patients treated with 100 mg/day of sertraline for 14 days was approximately 40% lower than in a similarly studied group of younger (25 to 32 year old) individuals. Steady-state, therefore, was achieved after 2 to 3 weeks in older patients. The same study showed a decreased clearance of desmethylsertraline in older males, but not in older females [See Use in Specific Populations (8.5)].

Hepatic Impairment

In patients with chronic mild liver impairment (N=10: 8 patients with Child-Pugh scores of 5 to 6; and 2 patients with Child-Pugh scores of 7 to 8) who received 50 mg of sertraline per day for 21 days, sertraline clearance was reduced, resulting in approximately 3-fold greater exposure compared to age-matched volunteers with normal hepatic function (N=10). The exposure to desmethylsertraline was approximately 2-fold greater in patients with mild hepatic impairment compared to age-matched volunteers with normal hepatic function. There were no significant differences in plasma protein binding observed between the two groups. The effects of sertraline in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment have not been studied [See Dosage and Administration (2.4), Use in Specific Populations (8.6)].

Renal Impairment

Sertraline is extensively metabolized and excretion of unchanged drug in urine is a minor route of elimination. In volunteers with mild to moderate (CLcr=30-60 mL/min), moderate to severe (CLcr=10-29 mL/min) or severe (receiving hemodialysis) renal impairment (N=10 each group), the pharmacokinetics and protein binding of 200 mg sertraline per day maintained for 21 days were not altered compared to age-matched volunteers (N=12) with no renal impairment. Thus, sertraline multiple dose pharmacokinetics appear to be unaffected by renal impairment [See Use in Specific Populations (8.7)].

Drug Interaction Studies

Pimozide

In a controlled study of a single dose (2 mg) of pimozide, 200 mg sertraline (once daily) co-administration to steady state was associated with a mean increase in pimozide AUC and Cmax of about 40%, but was not associated with any changes in ECG. The highest recommended pimozide dose (10 mg) has not been evaluated in combination with sertraline. The effect on QT interval and PK parameters at doses higher than 2 mg of pimozide are not known [See Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Drugs Metabolized by CYP2D6

Many antidepressant drugs (e.g., SSRIs, including sertraline, and most tricyclic antidepressant drugs) inhibit the biochemical activity of the drug metabolizing isozyme CYP2D6 (debrisoquin hydroxylase), and, thus, may increase the plasma concentrations of co-administered drugs that are metabolized by CYP2D6. The drugs for which this potential interaction is of greatest concern are those metabolized primarily by CYP2D6 and that have a narrow therapeutic index (e.g., tricyclic antidepressant drugs and the Type 1C antiarrhythmics propafenone and flecainide). The extent to which this interaction is an important clinical problem depends on the extent of the inhibition of CYP2D6 by the antidepressant and the therapeutic index of the co-administered drug. There is variability among the drugs effective in the treatment of MDD in the extent of clinically important 2D6 inhibition, and in fact sertraline at lower doses has a less prominent inhibitory effect on 2D6 than some others in the class. Nevertheless, even sertraline has the potential for clinically important 2D6 inhibition [See Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Phenytoin

Clinical trial data suggested that sertraline may increase phenytoin concentrations [See Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Cimetidine

In a study assessing disposition of sertraline (100 mg) on the second of 8 days of cimetidine administration (800 mg daily), there were increases in sertraline mean AUC (50%), Cmax (24%) and half-life (26%) compared to the placebo group [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Diazepam

In a study comparing the disposition of intravenously administered diazepam before and after 21 days of dosing with either sertraline (50 to 200 mg/day escalating dose) or placebo, there was a 32% decrease relative to baseline in diazepam clearance for the sertraline group compared to a 19% decrease relative to baseline for the placebo group (p<0.03). There was a 23% increase in Tmax for desmethyldiazepam in the sertraline group compared to a 20% decrease in the placebo group (p<0.03) [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Lithium

In a placebo-controlled trial in normal volunteers, the administration of two doses of sertraline did not significantly alter steady-state lithium levels or the renal clearance of lithium [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Tolbutamide

In a placebo-controlled trial in normal volunteers, administration of sertraline for 22 days (including 200 mg/day for the final 13 days) caused a statistically significant 16% decrease from baseline in the clearance of tolbutamide following an intravenous 1,000 mg dose. Sertraline administration did not noticeably change either the plasma protein binding or the apparent volume of distribution of tolbutamide, suggesting that the decreased clearance was due to a change in the metabolism of the drug [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Atenolol

Sertraline (100 mg) when administered to 10 healthy male subjects had no effect on the beta-adrenergic blocking ability of atenolol [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Digoxin

In a placebo-controlled trial in normal volunteers, administration of sertraline for 17 days (including 200 mg/day for the last 10 days) did not change serum digoxin levels or digoxin renal clearance [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Drugs Metabolized by CYP3A4

In three separate in vivo interaction studies, sertraline was co-administered with CYP3A4 substrates, terfenadine, carbamazepine, or cisapride under steady-state conditions. The results of these studies indicated that sertraline did not increase plasma concentrations of terfenadine, carbamazepine, or cisapride. These data indicate that sertraline’s extent of inhibition of CYP3A4 activity is not likely to be of clinical significance. Results of the interaction study with cisapride indicate that sertraline 200 mg (once daily) induces the metabolism of cisapride (cisapride AUC and Cmax were reduced by about 35%) [See Drug Interactions (7.2)].

Microsomal Enzyme Induction

Preclinical studies have shown sertraline to induce hepatic microsomal enzymes. In clinical studies, sertraline was shown to induce hepatic enzymes minimally as determined by a small (5%) but statistically significant decrease in antipyrine half-life following administration of 200 mg of sertraline per day for 21 days. This small change in antipyrine half-life reflects a clinically insignificant change in hepatic metabolism.

13 NONCLINICALTOXICOLOGY

13.1 Carcinogenesis, Mutagenesis, Impairment of Fertility

Carcinogenesis

Lifetime carcinogenicity studies were carried out in CD-1 mice and Long-Evans rats at doses up to 40 mg/kg/day. These doses correspond to 1 times (mice) and 2 times (rats) the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) of 200 mg/day on a mg/m2 basis. There was a dose-related increase of liver adenomas in male mice receiving sertraline at 10 to 40 mg/kg (0.25 to 1.0 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis). No increase was seen in female mice or in rats of either sex receiving the same treatments, nor was there an increase in hepatocellular carcinomas. Liver adenomas have a variable rate of spontaneous occurrence in the CD-1 mouse and are of unknown significance to humans. There was an increase in follicular adenomas of the thyroid in female rats receiving sertraline at 40 mg/kg (2 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis); this was not accompanied by thyroid hyperplasia. While there was an increase in uterine adenocarcinomas in rats receiving sertraline at 10 to 40 mg/kg (0.5 to 2.0 times the MRHD on a mg/m2 basis) compared to placebo controls, this effect was not clearly drug related.

Mutagenesis

Sertraline had no genotoxic effects, with or without metabolic activation, based on the following assays: bacterial mutation assay; mouse lymphoma mutation assay; and tests for cytogenetic aberrations in vivo in mouse bone marrow and in vitro in human lymphocytes.

Impairment of Fertility

A decrease in fertility was seen in one of two rat studies at a dose of 80 mg/kg (3.1 times the maximum recommended human dose on a mg/m2 basis in adolescents).

14 CLINICAL STUDIES

Efficacy of sertraline was established in the following trials:

- MDD: two short-term trials and one maintenance trials in adults [See Clinical Studies (14.1)].

- OCD: three short-term trials in adults and one short-term trial in pediatric patients [See Clinical Studies (14.2)].

- PD: three short-term trials and one maintenance trial in adults [See Clinical Studies (14.3)].

- PTSD: two short-term trials and one maintenance trial in adults [See Clinical Studies (14.4)].

- SAD: two short-term trials and one maintenance trial in adults [See Clinical Studies (14.5)].

- PMDD: two short-term trials in adult female patients [See Clinical Studies (14.6)].

14.1 Major Depressive Disorder

The efficacy of sertraline as a treatment for MDD was established in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies and one double-blind, randomized-withdrawal study following an open label study in adult (ages 18 to 65) outpatients who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) criteria for MDD (studies MDD-1 and MDD-2).

- Study MDD-1 was an 8-week, 3-arm study with flexible dosing of sertraline, amitriptyline, and placebo. Adult patients received sertraline (N=126, in a daily dose titrated weekly to 50 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg), amitriptyline (N=123, in a daily dose titrated weekly to 50 mg, 100 mg, or 150 mg), or placebo (N= 130).

- Study MDD-2 was a 6-week, multicenter parallel study of three fixed doses of sertraline administered once daily at 50 mg (N=82), 100 mg (N=75), and 200 mg (N=56) doses and placebo (N=76) in the treatment of adult outpatients with MDD.

Overall, these studies demonstrated sertraline to be superior to placebo on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) and the Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S) of Illness and Global Improvement (CGI-I) scores. Study MDD-2 was not readily interpretable regarding a dose response relationship for effectiveness.

A third study (Study MDD-3) involved adult outpatients meeting the DSM-III criteria for MDD who had responded by the end of an initial 8-week open treatment phase on sertraline 50 to 200 mg/day. These patients (n=295) were randomized to continuation on double-blind sertraline 50 to 200 mg/day or placebo for 44 weeks. A statistically significantly lower relapse rate was observed for patients taking sertraline compared to those on placebo: Sertraline [n=11 (8%)] and placebo [n=31 (39%)]. The mean sertraline dose for completers was 70 mg/day.

Analyses for gender effects on outcome did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of sex.

14.2 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Adults with OCD

The effectiveness of sertraline in the treatment of OCD was demonstrated in three multicenter placebo-controlled studies of adult (age 18 to 65) non-depressed outpatients (Studies OCD-1, OCD-2, and OCD-3). Patients in all three studies had moderate to severe OCD (DSM-III or DSM-III-R) with mean baseline ratings on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) total score ranging from 23 to 25.

- Study OCD-1 was an 8-week randomized, placebo-controlled study with flexible dosing of sertraline in a range of 50 to 200 mg/day, titrated in 50 mg increments every 4 days to a maximally tolerated dose; the mean dose for completers was 186 mg/day. Patients receiving sertraline (N=43) experienced a mean reduction of approximately 4 points on the Y-BOCS total score which was statistically significantly greater than the mean reduction of 2 points in placebo-treated patients (N=44). The mean change in Y-BOCS from baseline to last visit (the primary efficacy endpoint) was -3.79 (sertraline) and -1.48 (placebo).

- Study OCD-2 was a 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled fixed-dose study, including sertraline doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg/day. Sertraline (N=240) was titrated to the assigned dose over two weeks in 50 mg increments every 4 days. Patients receiving sertraline doses of 50 and 200 mg/day experienced mean reductions of approximately 6 points on the Y-BOCS total score, which were statistically significantly greater than the approximately 3 point reduction in placebo-treated patients (N=84). The mean change in Y-BOCS from baseline to last visit (the primary efficacy endpoint) was -5.7 (pooled results from sertraline 50 mg, 100 mg, and 150 mg) and -2.85 (placebo).

- Study OCD-3 was a 12-week randomized, placebo controlled study with flexible dosing of sertraline in a range of 50 to 200 mg/day; the mean dose for completers was 185 mg/day. Sertraline (N=241) was titrated to the assigned dose over two weeks in 50 mg increments every 4 days. Patients receiving sertraline experienced a mean reduction of approximately 7 points on the Y-BOCS total score which was statistically significantly greater than the mean reduction of approximately 4 points in placebo-treated patients (N=84). The mean change in Y-BOCS from baseline to last visit (the primary efficacy endpoint) was - 6.5 (sertraline) and -3.6 (placebo).

Analyses for age and gender effects on outcome did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of age or sex.

The effectiveness of sertraline was studied in the risk reduction of OCD relapse. In Study OCD-4, patients ranging in age from 18 to79 meeting DSM-III-R criteria for OCD who had responded during a 52-week single-blind trial on sertraline 50 to 200 mg/day (n=224) were randomized to continuation of sertraline or to substitution of placebo for up to 28 weeks of observation for analysis of discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response. Response during the single-blind phase was defined as a decrease in the Y-BOCS score of ≥25% compared to baseline and a CGI-I of 1 (very much improved), 2 (much improved) or 3 (minimally improved). Insufficient clinical response during the double-blind phase indicated a worsening of the patient’s condition that resulted in study discontinuation, as assessed by the investigator. Relapse during the double-blind phase was defined as the following conditions being met (on three consecutive visits for 1 and 2, and condition 3 being met at visit 3):

- Condition 1: Y-BOCS score increased by ≥ 5 points, to a minimum of 20, relative to baseline;

- Condition 2: CGI-I increased by ≥ one point; and

- Condition 3: Worsening of the patient’s condition in the investigator’s judgment, to justify alternative treatment.

Patients receiving continued sertraline treatment experienced a statistically significantly lower rate of discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response over the subsequent 28 weeks compared to those receiving placebo. This pattern was demonstrated in male and female subjects.

Pediatric Patients with OCD

The effectiveness of sertraline for the treatment of OCD was demonstrated in a 12-week, multicenter, placebo-controlled, parallel group study in a pediatric outpatient population (ages 6 to 17) (Study OCD-5). Sertraline (N=92) was initiated at doses of either 25 mg/day (pediatric patients ages 6 to12) or 50 mg/day (adolescents, ages 13 to 17), and then titrated at 3 and 4 day intervals (25 mg incremental dose for pediatric patients ages 6 to 12) or 1 week intervals (50 mg incremental dose adolescents ages 13 to 17) over the next four weeks to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day, as tolerated. The mean dose for completers was 178 mg/day. Dosing was once a day in the morning or evening. Patients in this study had moderate to severe OCD (DSM-III-R) with mean baseline ratings on the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) total score of 22. Patients receiving sertraline experienced a mean reduction of approximately 7 units on the CY-BOCS total score which was statistically significantly greater than the 3 unit reduction for placebo patients (n=95). Analyses for age and gender effects on outcome did not suggest any differential responsiveness on the basis of age or sex.

14.3 Panic Disorder

The effectiveness of sertraline in the treatment of PD was demonstrated in three double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (Studies PD-1, PD-2, and PD-3) of adult outpatients who had a primary diagnosis of PD (DSM-III-R), with or without agoraphobia.

- Studies PD-1 and PD-2 were 10-week flexible dose studies of sertraline (N=80 study PD-1 and N=88 study PD-2) compared to placebo (N=176 study PD-1 and PD-2). In both studies, sertraline was initiated at 25 mg/day for the first week, then titrated in weekly increments of 50 mg per day to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day on the basis of clinical response and toleration. The mean sertraline doses for completers to 10 weeks were 131 mg/day and 144 mg/day, respectively, for Studies PD-1 and PD-2. In these studies, sertraline was shown to be statistically significantly more effective than placebo on change from baseline in panic attack frequency and on the Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S) of Illness and Global Improvement (CGI-I) scores. The difference between sertraline and placebo in reduction from baseline in the number of full panic attacks was approximately 2 panic attacks per week in both studies.

- Study PD-3 was a 12-week randomized, double-blind fixed-dose study, including sertraline doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg/day. Patients receiving sertraline (50 mg N=43, 100 mg N=44, 200 mg N=45) experienced a statistically significantly greater reduction in panic attack frequency than patients receiving placebo (N=45). Study PD-3 was not readily interpretable regarding a dose response relationship for effectiveness.

Subgroup analyses did not indicate that there were any differences in treatment outcomes as a function of age, race, or gender.

In Study PD-4, patients meeting DSM-III-R criteria for PD who had responded during a 52-week open trial on sertraline 50 to 200 mg/day (n=183) were randomized to continuation of sertraline or to substitution of placebo for up to 28 weeks of observation for discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response. Response during the open phase was defined as a CGI-I score of 1(very much improved) or 2 (much improved). Insufficient clinical response in the double-blind phase indicated a worsening of the patient’s condition that resulted in study discontinuation, as assessed by the investigator. Relapse during the double-blind phase was defined as the following conditions being met on three consecutive visits:

(1) CGI-I ≥ 3;

(2) meets DSM-III-R criteria for PD;

(3) number of panic attacks greater than at baseline.

Patients receiving continued sertraline treatment experienced a statistically significantly lower rate of discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response over the subsequent 28 weeks compared to those receiving placebo. This pattern was demonstrated in male and female subjects.

14.4 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

The effectiveness of sertraline in the treatment of PTSD was established in two multicenter placebo-controlled studies (Studies PSTD-1 and PSTD-2) of adult outpatients who met DSM-III-R criteria for PTSD. The mean duration of PTSD for these patients was 12 years (Studies PSTD-1 and PSTD-2 combined) and 44% of patients (169 of the 385 patients treated) had secondary depressive disorder.

Studies PSTD-1 and PSTD-2 were 12-week flexible dose studies. Sertraline was initiated at 25 mg/day for the first week, and titrated in weekly increments of 50 mg per day to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day on the basis of clinical response and tolerability. The mean sertraline dose for completers was 146 mg/day and 151 mg/day, respectively, for Studies PSTD-1 and PSTD-2. Study outcome was assessed by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale Part 2 (CAPS), which is a multi-item instrument that measures the three PTSD diagnostic symptom clusters of reexperiencing/intrusion, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal as well as the patient-rated Impact of Event Scale (IES), which measures intrusion and avoidance symptoms. Patients receiving sertraline (N=99 and N=94, respectively) showed statistically significant improvement compared to placebo (N=83 and N=92) on change from baseline to endpoint on the CAPS, IES, and on the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI-S) Severity of Illness and Global Improvement (CGI-I) scores.

In two additional placebo-controlled PTSD trials (Studies PSTD-3 and PSTD-4), the difference in response to treatment between patients receiving sertraline and patients receiving placebo was not statistically significant. One of these additional studies was conducted in patients similar to those recruited for Studies PSTD-1 and PSTD-2, while the second additional study was conducted in predominantly male veterans.

As PTSD is a more common disorder in women than men, the majority (76%) of patients in Studies PSTD-1 and PSTD-2 described above were women. Post hoc exploratory analyses revealed a statistically significant difference between sertraline and placebo on the CAPS, IES and CGI in women, regardless of baseline diagnosis of comorbid major depressive disorder, but essentially no effect in the relatively smaller number of men in these studies. The clinical significance of this apparent gender effect is unknown at this time. There was insufficient information to determine the effect of race or age on outcome.

In Study PSTD-5, patients meeting DSM-III-R criteria for PTSD who had responded during a 24-week open trial on sertraline 50 to 200 mg/day (n=96) were randomized to continuation of sertraline or to substitution of placebo for up to 28 weeks of observation for relapse. Response during the open phase was defined as a CGI-I of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), and a decrease in the CAPS-2 score of > 30% compared to baseline. Relapse during the double-blind phase was defined as the following conditions being met on two consecutive visits:

(1) CGI-I ≥ 3;

(2) CAPS-2 score increased by ≥ 30% and by ≥ 15 points relative to baseline; and

(3) worsening of the patient's condition in the investigator's judgment.

Patients receiving continued sertraline treatment experienced statistically significantly lower relapse rates over the subsequent 28 weeks compared to those receiving placebo. This pattern was demonstrated in male and female subjects.

14.5 Social Anxiety Disorder

The effectiveness of sertraline in the treatment of SAD (also known as social phobia) was established in two multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled studies (Study SAD-1 and SAD-2) of adult outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for SAD.

Study SAD-1 was a 12-week, flexible dose study comparing sertraline (50 to 200 mg/day), n=211, to placebo, n=204, in which sertraline was initiated at 25 mg/day for the first week, then titrated to the maximum tolerated dose in 50 mg increments biweekly. Study outcomes were assessed by the:

(1) Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), a 24-item clinician administered instrument that measures fear, anxiety, and avoidance of social and performance situations, and

(2) Proportion of responders as defined by the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I) criterion of CGI-I ≤ 2 (very much or much improved).

Sertraline was statistically significantly more effective than placebo as measured by the LSAS and the percentage of responders.

Study SAD-2 was a 20-week, flexible dose study that compared sertraline (50 to 200 mg/day), n=135, to placebo, n=69. Sertraline was titrated to the maximum tolerated dose in 50 mg increments every 3 weeks. Study outcome was assessed by the:

(1) Duke Brief Social Phobia Scale (BSPS), a multi-item clinician-rated instrument that measures fear, avoidance and physiologic response to social or performance situations,

(2) Marks Fear Questionnaire Social Phobia Subscale (FQ-SPS), a 5-item patient-rated instrument that measures change in the severity of phobic avoidance and distress, and

(3) CGI-I responder criterion of ≤ 2.

Sertraline was shown to be statistically significantly more effective than placebo as measured by the BSPS total score and fear, avoidance and physiologic factor scores, as well as the FQ-SPS total score, and to have statistically significantly more responders than placebo as defined by the CGI-I. Subgroup analyses did not suggest differences in treatment outcome on the basis of gender. There was insufficient information to determine the effect of race or age on outcome.

In Study SAD-3, patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for SAD who had responded while assigned to sertraline (CGI-I of 1 or 2) during a 20-week placebo-controlled trial on sertraline 50-200 mg/day were randomized to continuation of sertraline or to substitution of placebo for up to 24 weeks of observation for relapse. Relapse was defined as ≥ 2 point increase in the Clinical Global Impression Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score compared to baseline or study discontinuation due to lack of efficacy. Patients receiving sertraline continuation treatment experienced a statistically significantly lower relapse rate during this 24-week period than patients randomized to placebo substitution.

14.6 Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

The effectiveness of sertraline for the treatment of PMDD was established in two double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled flexible dose trials (Studies PMDD-1 and PMDD-2) conducted over 3 menstrual cycles in adult female patients. The effectiveness of sertraline for PMDD for more than 3 menstrual cycles has not been systematically evaluated in controlled trials.

Patients in Study PMDD-1 met DSM-III-R criteria for Late Luteal Phase Dysphoric Disorder (LLPDD), the clinical entity referred to as PMDD in DSM-IV. Patients in Study PMDD-2 met DSM-IV criteria for PMDD. Study PMDD-1 utilized continuous daily dosing throughout the study, while Study PMDD-2 utilized luteal phase dosing (intermittent dosing) for the 2 weeks prior to the onset of menses. The mean duration of PMDD symptoms was approximately 10.5 years in both studies. Patients taking oral contraceptives were excluded from these trials; therefore, the efficacy of sertraline in combination with oral contraceptives for the treatment of PMDD is unknown.

Efficacy was assessed with the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP), a patient-rated instrument that mirrors the diagnostic criteria for PMDD as identified in the DSM-IV, and includes assessments for mood, physical symptoms, and other symptoms. Other efficacy assessments included the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17), and the Clinical Global Impression Severity of Illness (CGI-S) and Improvement (CGI-I) scores.

- In Study PMDD-1, involving 251 randomized patients, (n=125 on sertraline and n=126 on placebo), sertraline treatment was initiated at 50 mg/day and administered daily throughout the menstrual cycle. In subsequent cycles, sertraline was titrated in 50 mg increments at the beginning of each menstrual cycle up to a maximum of 150 mg/day on the basis of clinical response and tolerability. The mean dose for completers was 102 mg/day. Sertraline administered daily throughout the menstrual cycle was statistically significantly more effective than placebo on change from baseline to endpoint on the DRSP total score, the HAMD-17 total score, and the CGI-S score, as well as the CGI-I score at endpoint.

- In Study PMDD-2, involving 281 randomized patients, (n=142 on sertraline and n=139 on placebo), sertraline treatment was initiated at 50 mg/day in the late luteal phase (last 2 weeks) of each menstrual cycle and then discontinued at the onset of menses (intermittent dosing). In subsequent cycles, patients were dosed in the range of 50-100 mg/day in the luteal phase of each cycle, on the basis of clinical response and tolerability. Patients who received 100 mg/day started with 50 mg/day for the first 3 days of the cycle, then 100 mg/day for the remainder of the cycle. The mean sertraline dose for completers was 74 mg/day. Sertraline administered in the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle was statistically significantly more effective than placebo on change from baseline to endpoint on the DRSP total score and the CGI-S score, as well as the CGI-I score at endpoint (Week 12).

There was insufficient information to determine the effect of race or age on outcome in these studies.

16 HOW SUPPLIED/STORAGE AND HANDLING

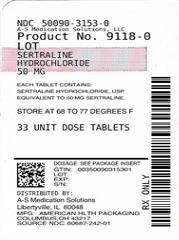

Product: 50090-3153

NDC: 50090-3153-0 1 TABLET in a BLISTER PACK / 33 in a BOX, UNIT-DOSE

17 PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION

Advise the patient to read the FDA-approved patient labeling (Medication Guide).

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

Advise patients and caregivers to look for the emergence of suicidality, especially early during treatment and when the dosage is adjusted up or down, and instruct them to report such symptoms to the healthcare provider [See Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

Serotonin Syndrome

Caution patients about the risk of serotonin syndrome, particularly with the concomitant use of sertraline with other serotonergic drugs including triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, St. John’s Wort, and with drugs that impair metabolism of serotonin (in particular, MAOIs, both those intended to treat psychiatric disorders and also others, such as linezolid). Patients should contact their health care provider or report to the emergency room if they experience signs or symptoms of serotonin syndrome [See Warnings and Precautions (5.2), Drug Interactions (7.1)].

Increased Risk of Bleeding

Inform patients about the concomitant use of sertraline with aspirin, NSAIDs, other antiplatelet drugs, warfarin, or other anticoagulants because the combined use has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Advise patients to inform their health care providers if they are taking or planning to take any prescription or over-the-counter medications that increase the risk of bleeding [See Warnings and Precautions (5.3)].

Activation of Mania/Hypomania