ZIPRASIDONE- ziprasidone capsule

REMEDYREPACK INC.

----------

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATIONThese highlights do not include all the information needed to use Ziprasidone safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for ziprasidone.

Ziprasidone capsules, for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 2001 WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSISSee full prescribing information for complete boxed warning.Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Ziprasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis ( 5.1) RECENT MAJOR CHANGES

INDICATIONS AND USAGEZiprasidone is an atypical antipsychotic. In choosing among treatments, prescribers should be aware of the capacity of ziprasidone to prolong the QT interval and may consider the use of other drugs first. ( 1) Ziprasidone capsules are indicated for the: DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

ADVERSE REACTIONSCommonly observed adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the incidence for placebo) were :

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Greenstone LLC at 1-800-438-1985 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch. DRUG INTERACTIONSUSE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONSPregnancy: May cause extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms in neonates with third trimester exposure. ( 8.1) See 17 for PATIENT COUNSELING INFORMATION and FDA-approved patient labeling. Revised: 12/2022 |

FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Ziprasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Warnings and Precautions (5.1)].

1 INDICATIONS AND USAGE

Ziprasidone is indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia, as monotherapy for the acute treatment of bipolar manic or mixed episodes, and as an adjunct to lithium or valproate for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. When deciding among the alternative treatments available for the condition needing treatment, the prescriber should consider the finding of ziprasidone's greater capacity to prolong the QT/QTc interval compared to several other antipsychotic drugs [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] . Prolongation of the QTc interval is associated in some other drugs with the ability to cause torsade de pointes-type arrhythmia, a potentially fatal polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and sudden death. In many cases this would lead to the conclusion that other drugs should be tried first. Whether ziprasidone will cause torsade de pointes or increase the rate of sudden death is not yet known [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] .

Schizophrenia

- Ziprasidone is indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults [see Clinical Studies (14.1)] .

Bipolar I Disorder (Acute Mixed or Manic Episodes and Maintenance Treatment as an Adjunct to Lithium or Valproate)

- Ziprasidone is indicated as monotherapy for the acute treatment of adults with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder [see Clinical Studies (14.2)].

- Ziprasidone is indicated as an adjunct to lithium or valproate for the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder in adults [see Clinical Studies (14.2)] .

2 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION

2.1 Administration Information for Ziprasidone Capsules

Administer ziprasidone capsules orally with food. Swallow capsules whole, do not open, crush, or chew the capsules.

2.2 Schizophrenia

Dose Selection

Ziprasidone capsules should be administered at an initial daily dose of 20 mg twice daily with food. In some patients, daily dosage may subsequently be adjusted on the basis of individual clinical status up to 80 mg twice daily. Dosage adjustments, if indicated, should generally occur at intervals of not less than 2 days, as steady-state is achieved within 1 to 3 days. In order to ensure use of the lowest effective dose, patients should ordinarily be observed for improvement for several weeks before upward dosage adjustment.

Efficacy in schizophrenia was demonstrated in a dose range of 20 mg to 100 mg twice daily in short-term, placebo-controlled clinical trials. There were trends toward dose response within the range of 20 mg to 80 mg twice daily, but results were not consistent. An increase to a dose greater than 80 mg twice daily is not generally recommended. The safety of doses above 100 mg twice daily has not been systematically evaluated in clinical trials [see Clinical Studies (14.1)] .

Maintenance Treatment

While there is no body of evidence available to answer the question of how long a patient treated with ziprasidone should remain on it, a maintenance study in patients who had been symptomatically stable and then randomized to continue ziprasidone or switch to placebo demonstrated a delay in time to relapse for patients receiving ziprasidone [see Clinical Studies (14.1)] . No additional benefit was demonstrated for doses above 20 mg twice daily. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment.

2.3 Bipolar I Disorder (Acute Mixed or Manic Episodes and Maintenance Treatment as an Adjunct to Lithium or Valproate)

Acute Treatment of Manic or Mixed Episodes

In adults oral ziprasidone should be administered at an initial daily dose of 40 mg twice daily with food. The dose may then be increased to 60 mg or 80 mg twice daily on the second day of treatment and subsequently adjusted on the basis of tolerance and efficacy within the range 40 mg–80 mg twice daily. In the flexible-dose clinical trials, the mean daily dose administered was approximately 120 mg [see Clinical Studies (14.2)] .

Maintenance Treatment (as an adjunct to lithium or valproate)

Continue treatment at the same dose on which the patient was initially stabilized, within the range of 40 mg–80 mg twice daily with food. Patients should be periodically reassessed to determine the need for maintenance treatment [see Clinical Studies (14.2)] .

3 DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS

Ziprasidone capsules are differentiated by capsule color/size and are imprinted in black ink with "G" and a unique number. Ziprasidone capsules are supplied for oral administration in 20 mg (blue/white), 40 mg (blue/blue), 60 mg (white/white), and 80 mg (blue/white) capsules. They are supplied in the following strengths and package configurations:

| Capsule Strength (mg) | Imprint |

|---|---|

| 20 | 2001 |

| 40 | 2002 |

| 60 | 2003 |

| 80 | 2004 |

4 CONTRAINDICATIONS

4.1 QT Prolongation

Because of ziprasidone's dose-related prolongation of the QT interval and the known association of fatal arrhythmias with QT prolongation by some other drugs, ziprasidone is contraindicated:

- in patients with a known history of QT prolongation (including congenital long QT syndrome)

- in patients with recent acute myocardial infarction

- in patients with uncompensated heart failure

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies between ziprasidone and other drugs that prolong the QT interval have not been performed. An additive effect of ziprasidone and other drugs that prolong the QT interval cannot be excluded. Therefore, ziprasidone should not be given with:

- dofetilide, sotalol, quinidine, other Class Ia and III anti-arrhythmics, mesoridazine, thioridazine, chlorpromazine, droperidol, pimozide, sparfloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, halofantrine, mefloquine, pentamidine, arsenic trioxide, levomethadyl acetate, dolasetron mesylate, probucol or tacrolimus.

- other drugs that have demonstrated QT prolongation as one of their pharmacodynamic effects and have this effect described in the full prescribing information as a contraindication or a boxed or bolded warning [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] .

5 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

5.1 Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients With Dementia-Related Psychosis

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of 17 placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group.

Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Ziprasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis. [see Boxed Warning, Warnings and Precautions (5.2)]

5.2 Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke, in Elderly Patients With Dementia-Related Psychosis

In placebo-controlled trials in elderly subjects with dementia, patients randomized to risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine had a higher incidence of stroke and transient ischemic attack, including fatal stroke. Ziprasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis [see Boxed Warning and Warnings and Precautions (5.1)] .

5.3 QT Prolongation and Risk of Sudden Death

Ziprasidone use should be avoided in combination with other drugs that are known to prolong the QTc interval [see Contraindications (4.1) and Drug Interactions (7.4)] . Additionally, clinicians should be alert to the identification of other drugs that have been consistently observed to prolong the QTc interval. Such drugs should not be prescribed with ziprasidone. Ziprasidone should also be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias [see Contraindications (4)].

A study directly comparing the QT/QTc prolonging effect of oral ziprasidone with several other drugs effective in the treatment of schizophrenia was conducted in patient volunteers. In the first phase of the trial, ECGs were obtained at the time of maximum plasma concentration when the drug was administered alone. In the second phase of the trial, ECGs were obtained at the time of maximum plasma concentration while the drug was co-administered with an inhibitor of the CYP4503A4 metabolism of the drug.

In the first phase of the study, the mean change in QTc from baseline was calculated for each drug, using a sample-based correction that removes the effect of heart rate on the QT interval. The mean increase in QTc from baseline for ziprasidone ranged from approximately 9 to 14 msec greater than for four of the comparator drugs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol), but was approximately 14 msec less than the prolongation observed for thioridazine.

In the second phase of the study, the effect of ziprasidone on QTc length was not augmented by the presence of a metabolic inhibitor (ketoconazole 200 mg twice daily).

In placebo-controlled trials in adults, oral ziprasidone increased the QTc interval compared to placebo by approximately 10 msec at the highest recommended daily dose of 160 mg. In clinical trials with oral ziprasidone, the electrocardiograms of 2/2988 (0.06%) patients who received ziprasidone and 1/440 (0.23%) patients who received placebo revealed QTc intervals exceeding the potentially clinically relevant threshold of 500 msec. In the ziprasidone-treated patients, neither case suggested a role of ziprasidone. One patient had a history of prolonged QTc and a screening measurement of 489 msec; QTc was 503 msec during ziprasidone treatment. The other patient had a QTc of 391 msec at the end of treatment with ziprasidone and upon switching to thioridazine experienced QTc measurements of 518 and 593 msec.

Some drugs that prolong the QT/QTc interval have been associated with the occurrence of torsade de pointes and with sudden unexplained death. The relationship of QT prolongation to torsade de pointes is clearest for larger increases (20 msec and greater) but it is possible that smaller QT/QTc prolongations may also increase risk, or increase it in susceptible individuals . Although torsade de pointes has not been observed in association with the use of ziprasidone in premarketing studies and experience is too limited to rule out an increased risk, there have been rare post-marketing reports (in the presence of multiple confounding factors) [see Adverse Reactions (6.2)] .

A study evaluating the QT/QTc prolonging effect of intramuscular ziprasidone, with intramuscular haloperidol as a control, was conducted in patient volunteers. In the trial, ECGs were obtained at the time of maximum plasma concentration following two injections of ziprasidone (20 mg then 30 mg) or haloperidol (7.5 mg then 10 mg) given four hours apart. Note that a 30 mg dose of intramuscular ziprasidone is 50% higher than the recommended therapeutic dose. The mean change in QTc from baseline was calculated for each drug, using a sample-based correction that removes the effect of heart rate on the QT interval. The mean increase in QTc from baseline for ziprasidone was 4.6 msec following the first injection and 12.8 msec following the second injection. The mean increase in QTc from baseline for haloperidol was 6.0 msec following the first injection and 14.7 msec following the second injection. In this study, no patients had a QTc interval exceeding 500 msec.

As with other antipsychotic drugs and placebo, sudden unexplained deaths have been reported in patients taking ziprasidone at recommended doses. The premarketing experience for ziprasidone did not reveal an excess risk of mortality for ziprasidone compared to other antipsychotic drugs or placebo, but the extent of exposure was limited, especially for the drugs used as active controls and placebo. Nevertheless, ziprasidone's larger prolongation of QTc length compared to several other antipsychotic drugs raises the possibility that the risk of sudden death may be greater for ziprasidone than for other available drugs for treating schizophrenia. This possibility needs to be considered in deciding among alternative drug products [see Indications and Usage (1)].

Certain circumstances may increase the risk of the occurrence of torsade de pointes and/or sudden death in association with the use of drugs that prolong the QTc interval, including (1) bradycardia; (2) hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia; (3) concomitant use of other drugs that prolong the QTc interval; and (4) presence of congenital prolongation of the QT interval.

It is recommended that patients being considered for ziprasidone treatment who are at risk for significant electrolyte disturbances, hypokalemia in particular, have baseline serum potassium and magnesium measurements. Hypokalemia (and/or hypomagnesemia) may increase the risk of QT prolongation and arrhythmia. Hypokalemia may result from diuretic therapy, diarrhea, and other causes. Patients with low serum potassium and/or magnesium should be repleted with those electrolytes before proceeding with treatment. It is essential to periodically monitor serum electrolytes in patients for whom diuretic therapy is introduced during ziprasidone treatment. Persistently prolonged QTc intervals may also increase the risk of further prolongation and arrhythmia, but it is not clear that routine screening ECG measures are effective in detecting such patients. Rather, ziprasidone should be avoided in patients with histories of significant cardiovascular illness, e.g., QT prolongation, recent acute myocardial infarction, uncompensated heart failure, or cardiac arrhythmia. Ziprasidone should be discontinued in patients who are found to have persistent QTc measurements >500 msec.

For patients taking ziprasidone who experience symptoms that could indicate the occurrence of torsade de pointes, e.g., dizziness, palpitations, or syncope, the prescriber should initiate further evaluation, e.g., Holter monitoring may be useful.

5.4 Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

A potentially fatal symptom complex sometimes referred to as Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) has been reported in association with administration of antipsychotic drugs. Clinical manifestations of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and evidence of autonomic instability (irregular pulse or blood pressure, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and cardiac dysrhythmia). Additional signs may include elevated creatinine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis), and acute renal failure.

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with this syndrome is complicated. In arriving at a diagnosis, it is important to exclude cases where the clinical presentation includes both serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection, etc.) and untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal signs and symptoms (EPS). Other important considerations in the differential diagnosis include central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, drug fever, and primary central nervous system (CNS) pathology.

The management of NMS should include: (1) immediate discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs and other drugs not essential to concurrent therapy; (2) intensive symptomatic treatment and medical monitoring; and (3) treatment of any concomitant serious medical problems for which specific treatments are available. There is no general agreement about specific pharmacological treatment regimens for NMS.

If a patient requires antipsychotic drug treatment after recovery from NMS, the potential reintroduction of drug therapy should be carefully considered. The patient should be carefully monitored, since recurrences of NMS have been reported.

5.5 Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS)

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) has been reported with ziprasidone exposure. DRESS consists of a combination of three or more of the following: cutaneous reaction (such as rash or exfoliative dermatitis), eosinophilia, fever, lymphadenopathy and one or more systemic complications such as hepatitis, nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and pericarditis. DRESS is sometimes fatal. Discontinue ziprasidone if DRESS is suspected.

5.6 Tardive Dyskinesia

A syndrome of potentially irreversible, involuntary, dyskinetic movements may develop in patients undergoing treatment with antipsychotic drugs. Although the prevalence of the syndrome appears to be highest among the elderly, especially elderly women, it is impossible to rely upon prevalence estimates to predict, at the inception of antipsychotic treatment, which patients are likely to develop the syndrome. Whether antipsychotic drug products differ in their potential to cause tardive dyskinesia is unknown.

The risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and the likelihood that it will become irreversible are believed to increase as the duration of treatment and the total cumulative dose of antipsychotic drugs administered to the patient increase. However, the syndrome can develop, although much less commonly, after relatively brief treatment periods at low doses.

There is no known treatment for established cases of tardive dyskinesia, although the syndrome may remit, partially or completely, if antipsychotic treatment is withdrawn. Antipsychotic treatment itself, however, may suppress (or partially suppress) the signs and symptoms of the syndrome, and thereby may possibly mask the underlying process. The effect that symptomatic suppression has upon the long-term course of the syndrome is unknown.

Given these considerations, ziprasidone should be prescribed in a manner that is most likely to minimize the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. Chronic antipsychotic treatment should generally be reserved for patients who suffer from a chronic illness that (1) is known to respond to antipsychotic drugs, and (2) for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate. In patients who do require chronic treatment, the smallest dose and the shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response should be sought. The need for continued treatment should be reassessed periodically.

If signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear in a patient on ziprasidone, drug discontinuation should be considered. However, some patients may require treatment with ziprasidone despite the presence of the syndrome.

5.7 Metabolic Changes

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular/cerebrovascular risk. These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and body weight gain. While all of the drugs in the class have been shown to produce some metabolic changes, each drug has its own specific risk profile.

Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus, in some cases extreme and associated with ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma or death, have been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. There have been few reports of hyperglycemia or diabetes in patients treated with ziprasidone. Although fewer patients have been treated with ziprasidone, it is not known if this more limited experience is the sole reason for the paucity of such reports. Assessment of the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and glucose abnormalities is complicated by the possibility of an increased background risk of diabetes mellitus in patients with schizophrenia and the increasing incidence of diabetes mellitus in the general population. Given these confounders, the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and hyperglycemia-related adverse reactions is not completely understood. Precise risk estimates for hyperglycemia-related adverse reactions in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics are not available.

Patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. Patients with risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes) who are starting treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing at the beginning of treatment and periodically during treatment. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia during treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of antidiabetic treatment despite discontinuation of the suspect drug.

Pooled data from short-term, placebo-controlled studies in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are presented in Tables 1–4. Note that for the flexible dose studies in both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, each subject is categorized as having received either low (20–40 mg BID) or high (60–80 mg BID) dose based on the subject's modal daily dose. In the tables showing categorical changes, the percentages (% column) are calculated as 100×(n/N).

| Mean Random Glucose Change from Baseline mg/dL (N) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ziprasidone | Placebo | |||||

| 5 mg BID | 20 mg BID | 40 mg BID | 60 mg BID | 80 mg BID | 100 mg BID | |

|

||||||

| -1.1 (N=45) | +2.4 (N=179) | -0.2 (N=146) | -0.5 (N=119) | -1.7 (N=104) | +4.1 (N=85) | +1.4 (N=260) |

| Laboratory Analyte | Category Change (at least once) from Baseline | Treatment Arm | N | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Random Glucose | Normal to High (<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 438 | 77 (17.6%) |

| Placebo | 169 | 26 (15.4%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥100 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 159 | 54 (34.0%) | |

| Placebo | 66 | 22 (33.3%) | ||

In long-term (at least 1 year), placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studies in schizophrenia, the mean change from baseline in random glucose for ziprasidone 20–40 mg BID was -3.4 mg/dL (N=122); for ziprasidone 60–80 mg BID was +1.3 mg/dL (N=10); and for placebo was +0.3 mg/dL (N=71).

| Mean Fasting Glucose Change from Baseline mg/dL (N) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ziprasidone | Placebo | |

| Low Dose: 20–40 mg BID | High Dose: 60–80 mg BID | |

|

||

| +0.1 (N=206) | +1.6 (N=166) | +1.4 (N=287) |

| Laboratory Analyte | Category Change (at least once) from Baseline | Treatment Arm | N | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Fasting Glucose | Normal to High (<100 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 272 | 5 (1.8%) |

| Placebo | 210 | 2 (1.0%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥100 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL to ≥126 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 79 | 12 (15.2%) | |

| Placebo | 71 | 7 (9.9%) | ||

Dyslipidemia

Undesirable alterations in lipids have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Pooled data from short-term, placebo-controlled studies in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are presented in Tables 5–8.

| Mean Lipid Change from Baseline mg/dL (N) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Analyte | Ziprasidone | Placebo | |||||

| 5 mg BID | 20 mg BID | 40 mg BID | 60 mg BID | 80 mg BID | 100 mg BID | ||

|

|||||||

| Triglycerides | -12.9 (N=45) | -9.6 (N=181) | -17.3 (N=146) | -0.05 (N=120) | -16.0 (N=104) | +0.8 (N=85) | -18.6 (N=260) |

| Total Cholesterol | -3.6 (N=45) | -4.4 (N=181) | -8.2 (N=147) | -3.6 (N=120) | -10.0 (N=104) | -3.6 (N=85) | -4.7 (N=261) |

| Laboratory Analyte | Category Change (at least once) from Baseline | Treatment Arm | N | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Triglycerides | Increase by ≥50 mg/dL | Ziprasidone | 681 | 232 (34.1%) |

| Placebo | 260 | 53 (20.4%) | ||

| Normal to High (<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 429 | 63 (14.7%) | |

| Placebo | 152 | 12 (7.9%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥150 mg/dL and <200 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 92 | 43 (46.7%) | |

| Placebo | 41 | 12 (29.3%) | ||

| Total Cholesterol | Increase by ≥40 mg/dL | Ziprasidone | 682 | 76 (11.1%) |

| Placebo | 261 | 26 (10.0%) | ||

| Normal to High (<200 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 380 | 15 (3.9%) | |

| Placebo | 145 | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥200 mg/dL and <240 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 207 | 56 (27.1%) | |

| Placebo | 82 | 22 (26.8%) | ||

In long-term (at least 1 year), placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studies in schizophrenia, the mean change from baseline in random triglycerides for ziprasidone 20–40 mg BID was +26.3 mg/dL (N=15); for ziprasidone 60–80 mg BID was -39.3 mg/dL (N=10); and for placebo was +12.9 mg/dL (N=9). In long-term (at least 1 year), placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studies in schizophrenia, the mean change from baseline in random total cholesterol for ziprasidone 20–40 mg BID was +2.5 mg/dL (N=14); for ziprasidone 60–80 mg BID was -19.7 mg/dL (N=10); and for placebo was -28.0 mg/dL (N=9).

| Laboratory Analyte | Mean Change from Baseline mg/dL (N) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ziprasidone | Placebo | ||

| Low Dose: 20–40 mg BID | High Dose: 60–80 mg BID | ||

|

|||

| Fasting Triglycerides | +0.95 (N=206) | -3.5 (N=165) | +8.6 (N=286) |

| Fasting Total Cholesterol | -2.8 (N=206) | -3.4 (N=165) | -1.6 (N=286) |

| Fasting LDL Cholesterol | -3.0 (N=201) | -3.1 (N=158) | -1.97 (N=270) |

| Fasting HDL cholesterol | -0.09 (N=206) | +0.3 (N=165) | -0.9 (N=286) |

| Laboratory Analyte | Category Change (at least once) from Baseline | Treatment Arm | N | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Fasting Triglycerides | Increase by ≥50 mg/dL | Ziprasidone | 371 | 66 (17.8%) |

| Placebo | 286 | 62 (21.7%) | ||

| Normal to High (<150 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 225 | 15 (6.7%) | |

| Placebo | 179 | 13 (7.3%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥150 mg/dL and <200 mg/dL to ≥200 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 58 | 16 (27.6%) | |

| Placebo | 47 | 14 (29.8%) | ||

| Fasting Total Cholesterol | Increase by ≥40 mg/dL | Ziprasidone | 371 | 30 (8.1%) |

| Placebo | 286 | 13 (4.5%) | ||

| Normal to High (<200 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 204 | 5 (2.5%) | |

| Placebo | 151 | 2 (1.3%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥200 mg/dL and <240 mg/dL to ≥240 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 106 | 10 (9.4%) | |

| Placebo | 87 | 15 (17.2%) | ||

| Fasting LDL Cholesterol | Increase by ≥30 mg/dL | Ziprasidone | 359 | 39 (10.9%) |

| Placebo | 270 | 17 (6.3%) | ||

| Normal to High (<100 mg/dL to ≥160 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 115 | 0 (0%) | |

| Placebo | 89 | 1 (1.1%) | ||

| Borderline to High (≥100 mg/dL and <160 mg/dL to ≥160 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 193 | 18 (9.3%) | |

| Placebo | 141 | 14 (9.9%) | ||

| Fasting HDL | Normal (>=40 mg/dL) to Low (<40 mg/dL) | Ziprasidone | 283 | 22 (7.8%) |

| Placebo | 220 | 24 (10.9%) | ||

Weight Gain

Weight gain has been observed with atypical antipsychotic use. Monitoring of weight is recommended. Pooled data from short-term, placebo-controlled studies in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are presented in Tables 9–10.

| Ziprasidone | Placebo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg BID | 20 mg BID | 40 mg BID | 60 mg BID | 80 mg BID | 100 mg BID | |

| Mean Weight (kg) Changes from Baseline (N) | ||||||

| +0.3 (N=40) | +1.0 (N=167) | +1.0 (N=135) | +0.7 (N=109) | +1.1 (N=97) | +0.9 (N=74) | -0.4 (227) |

| Proportion of Patients With ≥7% Increase in Weight from Baseline (N) | ||||||

| 0.0% (N=40) | 9.0% (N=167) | 10.4% (N=135) | 7.3% (N=109) | 15.5% (N=97) | 10.8% (N=74) | 4.0% (N=227) |

In long-term (at least 1 year), placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studies in schizophrenia, the mean change from baseline weight for ziprasidone 20–40 mg BID was -2.3 kg (N=124); for ziprasidone 60–80 mg BID was +2.5 kg (N=10); and for placebo was -2.9 kg (N=72). In the same long-term studies, the proportion of subjects with ≥ 7% increase in weight from baseline for ziprasidone 20–40 mg BID was 5.6% (N=124); for ziprasidone 60–80 mg BID was 20.0% (N=10), and for placebo was 5.6% (N=72). In a long-term (at least 1 year), placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study in schizophrenia, the mean change from baseline weight for ziprasidone 20 mg BID was -2.6 kg (N=72); for ziprasidone 40 mg BID was -3.3 kg (N=69); for ziprasidone 80 mg BID was -2.8 kg (N=70) and for placebo was -3.8 kg (N=70). In the same long-term fixed-dose schizophrenia study, the proportion of subjects with ≥ 7% increase in weight from baseline for ziprasidone 20 mg BID was 5.6% (N=72); for ziprasidone 40 mg BID was 2.9% (N=69); for ziprasidone 80 mg BID was 5.7% (N=70) and for placebo was 2.9% (N=70).

| Ziprasidone | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| Low Dose: 20–40 mg BID | High Dose *: 60–80 mg BID | |

|

||

| Mean Weight (kg) Changes from Baseline (N) | ||

| +0.4 (N=295) | +0.4 (N=388) | +0.1 (N=451) |

| Proportion of Patients With ≥ 7% Increase in Weight from Baseline (N) | ||

| 2.4% (N=295) | 4.4% (N=388) | 1.8% (N=451) |

Schizophrenia - The proportions of patients meeting a weight gain criterion of ≥ 7% of body weight were compared in a pool of four 4- and 6-week placebo-controlled schizophrenia clinical trials, revealing a statistically significantly greater incidence of weight gain for ziprasidone (10%) compared to placebo (4%). A median weight gain of 0.5 kg was observed in ziprasidone patients compared to no median weight change in placebo patients. In this set of clinical trials, weight gain was reported as an adverse reaction in 0.4% and 0.4% of ziprasidone and placebo patients, respectively. During long-term therapy with ziprasidone, a categorization of patients at baseline on the basis of body mass index (BMI) revealed the greatest mean weight gain and highest incidence of clinically significant weight gain (> 7% of body weight) in patients with low BMI (<23) compared to normal (23–27) or overweight patients (>27). There was a mean weight gain of 1.4 kg for those patients with a "low" baseline BMI, no mean change for patients with a "normal" BMI, and a 1.3 kg mean weight loss for patients who entered the program with a "high" BMI.

Bipolar Disorder – During a 6-month placebo-controlled bipolar maintenance study in adults with ziprasidone as an adjunct to lithium or valproate, the incidence of clinically significant weight gain (≥ 7% of body weight) during the double-blind period was 5.6% for both ziprasidone and placebo treatment groups who completed the 6 months of observation for relapse. Interpretation of these findings should take into consideration that only patients who adequately tolerated ziprasidone entered the double-blind phase of the study, and there were substantial dropouts during the open label phase.

5.8 Rash

In premarketing trials with ziprasidone, about 5% of patients developed rash and/or urticaria, with discontinuation of treatment in about one-sixth of these cases. The occurrence of rash was related to dose of ziprasidone, although the finding might also be explained by the longer exposure time in the higher dose patients. Several patients with rash had signs and symptoms of associated systemic illness, e.g., elevated WBCs. Most patients improved promptly with adjunctive treatment with antihistamines or steroids and/or upon discontinuation of ziprasidone, and all patients experiencing these reactions were reported to recover completely. Upon appearance of rash for which an alternative etiology cannot be identified, ziprasidone should be discontinued.

5.9 Orthostatic Hypotension

Ziprasidone may induce orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness, tachycardia, and, in some patients, syncope, especially during the initial dose-titration period, probably reflecting its α 1-adrenergic antagonist properties. Syncope was reported in 0.6% of the patients treated with ziprasidone.

Ziprasidone should be used with particular caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease, heart failure or conduction abnormalities), cerebrovascular disease, or conditions which would predispose patients to hypotension (dehydration, hypovolemia, and treatment with antihypertensive medications).

5.10 Falls

Antipsychotic drugs (which include ziprasidone) may cause somnolence, postural hypotension, and motor and sensory instability, which could lead to falls and, consequently, fractures or other injuries. For patients with diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate these effects, complete fall risk assessments when initiating antipsychotic treatment and recurrently for patients on long-term antipsychotic therapy.

5.11 Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

In clinical trial and postmarketing experience, events of leukopenia/neutropenia have been reported temporally related to antipsychotic agents. Agranulocytosis (including fatal cases) has also been reported.

Possible risk factors for leukopenia/neutropenia include pre-existing low white blood cell count (WBC) and history of drug induced leukopenia/neutropenia. Patients with a pre-existing low WBC or a history of drug induced leukopenia/neutropenia should have their complete blood count (CBC) monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and should discontinue ziprasidone at the first sign of decline in WBC in the absence of other causative factors.

Patients with neutropenia should be carefully monitored for fever or other symptoms or signs of infection and treated promptly if such symptoms or signs occur. Patients with severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <1000/mm3) should discontinue ziprasidone and have their WBC followed until recovery.

5.12 Seizures

During clinical trials, seizures occurred in 0.4% of patients treated with ziprasidone. There were confounding factors that may have contributed to the occurrence of seizures in many of these cases. As with other antipsychotic drugs, ziprasidone should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that potentially lower the seizure threshold, e.g., Alzheimer's dementia. Conditions that lower the seizure threshold may be more prevalent in a population of 65 years or older.

5.13 Dysphagia

Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with antipsychotic drug use. Aspiration pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in elderly patients, in particular those with advanced Alzheimer's dementia. Ziprasidone and other antipsychotic drugs should be used cautiously in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia [see Boxed Warning] .

5.14 Hyperprolactinemia

As with other drugs that antagonize dopamine D 2 receptors, ziprasidone elevates prolactin levels in humans. Increased prolactin levels were also observed in animal studies with this compound, and were associated with an increase in mammary gland neoplasia in mice; a similar effect was not observed in rats [see Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)] . Tissue culture experiments indicate that approximately one-third of human breast cancers are prolactin-dependent in vitro, a factor of potential importance if the prescription of these drugs is contemplated in a patient with previously detected breast cancer. Neither clinical studies nor epidemiologic studies conducted to date have shown an association between chronic administration of this class of drugs and tumorigenesis in humans; the available evidence is considered too limited to be conclusive at this time.

Although disturbances such as galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and impotence have been reported with prolactin-elevating compounds, the clinical significance of elevated serum prolactin levels is unknown for most patients. Long-standing hyperprolactinemia when associated with hypogonadism may lead to decreased bone density.

5.15 Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment

Somnolence was a commonly reported adverse reaction in patients treated with ziprasidone. In the 4- and 6-week placebo-controlled trials in adults, somnolence was reported in 14% of patients on ziprasidone compared to 7% of placebo patients. Somnolence led to discontinuation in 0.3% of the patients in short-term clinical trials in adults.

Since ziprasidone has the potential to impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills, patients should be cautioned about performing activities requiring mental alertness, such as operating a motor vehicle (including automobiles) or operating hazardous machinery until they are reasonably certain that ziprasidone therapy does not affect them adversely.

5.16 Priapism

One case of priapism was reported in the premarketing database. While the relationship of the reaction to ziprasidone use has not been established, other drugs with alpha-adrenergic blocking effects have been reported to induce priapism, and it is possible that ziprasidone may share this capacity. Severe priapism may require surgical intervention.

5.17 Body Temperature Regulation

Although not reported with ziprasidone in premarketing trials, disruption of the body's ability to reduce core body temperature has been attributed to antipsychotic agents. Appropriate care is advised when prescribing ziprasidone for patients who will be experiencing conditions which may contribute to an elevation in core body temperature, e.g., exercising strenuously, exposure to extreme heat, receiving concomitant medication with anticholinergic activity, or being subject to dehydration.

5.18 Suicide

The possibility of a suicide attempt is inherent in psychotic illness or bipolar disorder, and close supervision of high-risk patients should accompany drug therapy. Prescriptions for ziprasidone should be written for the smallest quantity of capsules consistent with good patient management in order to reduce the risk of overdose.

5.19 Patients With Concomitant Illnesses

Clinical experience with ziprasidone in patients with certain concomitant systemic illnesses is limited [see Use in Specific Populations (8.6), (8.7)] .

Ziprasidone has not been evaluated or used to any appreciable extent in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable heart disease. Patients with these diagnoses were excluded from premarketing clinical studies. Because of the risk of QTc prolongation and orthostatic hypotension with ziprasidone, caution should be observed in cardiac patients [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3), (5.9)].

5.20 Laboratory Tests

Patients being considered for ziprasidone treatment that are at risk of significant electrolyte disturbances should have baseline serum potassium and magnesium measurements. Low serum potassium and magnesium should be replaced before proceeding with treatment. Patients who are started on diuretics during ziprasidone therapy need periodic monitoring of serum potassium and magnesium. Ziprasidone should be discontinued in patients who are found to have persistent QTc measurements >500 msec [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] .

6 ADVERSE REACTIONS

6.1 Clinical Trials Experience

Because clinical trials are conducted under widely varying conditions, adverse reaction rates observed in the clinical trials of a drug cannot be directly compared to rates in the clinical trials of another drug and may not reflect the rates observed in practice.

Clinical trials in adults for oral ziprasidone included approximately 5700 patients and/or normal subjects exposed to one or more doses of ziprasidone. Of these 5700, over 4800 were patients who participated in multiple-dose effectiveness trials, and their experience corresponded to approximately 1831 patient-years. These patients include: (1) 4331 patients who participated in multiple-dose trials, predominantly in schizophrenia, representing approximately 1698 patient-years of exposure as of February 5, 2000; and (2) 472 patients who participated in bipolar mania trials representing approximately 133 patient-years of exposure. An additional 127 patients with bipolar disorder participated in a long-term maintenance treatment study representing approximately 74.7 patient-years of exposure to ziprasidone. The conditions and duration of treatment with ziprasidone included open-label and double-blind studies, inpatient and outpatient studies, and short-term and longer-term exposure.

Adverse reactions during exposure were obtained by collecting voluntarily reported adverse experiences, as well as results of physical examinations, vital signs, weights, laboratory analyses, ECGs, and results of ophthalmologic examinations.

The stated frequencies of adverse reactions represent the proportion of individuals who experienced, at least once, a treatment-emergent adverse reaction of the type listed. A reaction was considered treatment emergent if it occurred for the first time or worsened while receiving therapy following baseline evaluation.

Adverse Findings Observed in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials with Oral Ziprasidone

The following findings are based on the short-term placebo-controlled premarketing trials for schizophrenia (a pool of two 6-week, and two 4-week fixed-dose trials) and bipolar mania (a pool of two 3-week flexible-dose trials) in which ziprasidone was administered in doses ranging from 10 to 200 mg/day.

Commonly Observed Adverse Reactions in Short Term-Placebo-Controlled Trials

The following adverse reactions were the most commonly observed adverse reactions associated with the use of ziprasidone (incidence of 5% or greater) and not observed at an equivalent incidence among placebo-treated patients (ziprasidone incidence at least twice that for placebo):

Schizophrenia trials ( see Table 11)

- Somnolence

- Respiratory Tract Infection

Bipolar trials ( see Table 12)

- Somnolence

- Extrapyramidal Symptoms which includes the following adverse reaction terms: extrapyramidal syndrome, hypertonia, dystonia, dyskinesia, hypokinesia, tremor, paralysis and twitching. None of these adverse reactions occurred individually at an incidence greater than 10% in bipolar mania trials.

- Dizziness which includes the adverse reaction terms dizziness and lightheadedness.

- Akathisia

- Abnormal Vision

- Asthenia

- Vomiting

SCHIZOPHRENIA

Adverse Reactions Associated With Discontinuation of Treatment in Short-Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials of Oral Ziprasidone

Approximately 4.1% (29/702) of ziprasidone-treated patients in short-term, placebo-controlled studies discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with about 2.2% (6/273) on placebo. The most common reaction associated with dropout was rash, including 7 dropouts for rash among ziprasidone patients (1%) compared to no placebo patients [see Warnings and Precautions (5.8)].

Adverse Reactions Occurring at an Incidence of 2% or More Among Ziprasidone-Treated Patients in Short-Term, Oral, Placebo-Controlled Trials

Table 11 enumerates the incidence, rounded to the nearest percent, of treatment-emergent adverse reactions that occurred during acute therapy (up to 6 weeks) in predominantly patients with schizophrenia, including only those reactions that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with ziprasidone and for which the incidence in patients treated with ziprasidone was greater than the incidence in placebo-treated patients.

| Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction | ||

|---|---|---|

| Body System/Adverse Reaction | Ziprasidone

(N=702) | Placebo

(N=273) |

|

||

| Body as a Whole | ||

| Asthenia | 5 | 3 |

| Accidental Injury | 4 | 2 |

| Chest Pain | 3 | 2 |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Tachycardia | 2 | 1 |

| Digestive | ||

| Nausea | 10 | 7 |

| Constipation | 9 | 8 |

| Dyspepsia | 8 | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 4 |

| Dry Mouth | 4 | 2 |

| Anorexia | 2 | 1 |

| Nervous | ||

| Extrapyramidal Symptoms * | 14 | 8 |

| Somnolence | 14 | 7 |

| Akathisia | 8 | 7 |

| Dizziness † | 8 | 6 |

| Respiratory | ||

| Respiratory Tract Infection | 8 | 3 |

| Rhinitis | 4 | 2 |

| Cough Increased | 3 | 1 |

| Skin and Appendages | ||

| Rash | 4 | 3 |

| Fungal Dermatitis | 2 | 1 |

| Special Senses | ||

| Abnormal Vision | 3 | 2 |

Dose Dependency of Adverse Reactions in Short-Term, Fixed-Dose, Placebo-Controlled Trials

An analysis for dose response in the schizophrenia 4-study pool revealed an apparent relation of adverse reaction to dose for the following reactions: asthenia, postural hypotension, anorexia, dry mouth, increased salivation, arthralgia, anxiety, dizziness, dystonia, hypertonia, somnolence, tremor, rhinitis, rash, and abnormal vision .

Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS)

The incidence of reported EPS (which included the adverse reaction terms extrapyramidal syndrome, hypertonia, dystonia, dyskinesia, hypokinesia, tremor, paralysis and twitching) for ziprasidone-treated patients in the short-term, placebo-controlled schizophrenia trials was 14% vs. 8% for placebo. Objectively collected data from those trials on the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (for EPS) and the Barnes Akathisia Scale (for akathisia) did not generally show a difference between ziprasidone and placebo.

Dystonia

Class Effect: Symptoms of dystonia, prolonged abnormal contractions of muscle groups, may occur in susceptible individuals during the first few days of treatment. Dystonic symptoms include: spasm of the neck muscles, sometimes progressing to tightness of the throat, swallowing difficulty, difficulty breathing, and/or protrusion of the tongue. While these symptoms can occur at low doses, they occur more frequently and with greater severity with high potency and at higher doses of first generation antipsychotic drugs. An elevated risk of acute dystonia is observed in males and younger age groups.

Vital Sign Changes

Ziprasidone is associated with orthostatic hypotension [see Warnings and Precautions (5.9)]

ECG Changes

Ziprasidone is associated with an increase in the QTc interval [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] . In the schizophrenia trials, ziprasidone was associated with a mean increase in heart rate of 1.4 beats per minute compared to a 0.2 beats per minute decrease among placebo patients.

Other Adverse Reactions Observed During the Premarketing Evaluation of Oral Ziprasidone

Following is a list of COSTART terms that reflect treatment-emergent adverse reactions as defined in the introduction to the ADVERSE REACTIONS section reported by patients treated with ziprasidone in schizophrenia trials at multiple doses >4 mg/day within the database of 3834 patients. All reported reactions are included except those already listed in Table 11 or elsewhere in labeling, those reaction terms that were so general as to be uninformative, reactions reported only once and that did not have a substantial probability of being acutely life-threatening, reactions that are part of the illness being treated or are otherwise common as background reactions, and reactions considered unlikely to be drug-related. It is important to emphasize that, although the reactions reported occurred during treatment with ziprasidone, they were not necessarily caused by it.

Adverse reactions are further categorized by body system and listed in order of decreasing frequency according to the following definitions:

Frequent - adverse reactions occurring in at least 1/100 patients (≥1.0% of patients) (only those not already listed in the tabulated results from placebo-controlled trials appear in this listing);

Infrequent - adverse reactions occurring in 1/100 to 1/1000 patients (in 0.1–1.0% of patients)

Rare – adverse reactions occurring in fewer than 1/1000 patients (<0.1% of patients).

Body as a Whole

| Frequent | abdominal pain, flu syndrome, fever, accidental fall, face edema, chills, photosensitivity reaction, flank pain, hypothermia, motor vehicle accident |

Cardiovascular System

| Frequent | tachycardia, hypertension, postural hypotension |

| Infrequent | bradycardia, angina pectoris, atrial fibrillation |

| Rare | first degree AV block, bundle branch block, phlebitis, pulmonary embolus, cardiomegaly, cerebral infarct, cerebrovascular accident, deep thrombophlebitis, myocarditis, thrombophlebitis |

Digestive System

| Frequent | anorexia, vomiting |

| Infrequent | rectal hemorrhage, dysphagia, tongue edema |

| Rare | gum hemorrhage, jaundice, fecal impaction, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase increased, hematemesis, cholestatic jaundice, hepatitis, hepatomegaly, leukoplakia of mouth, fatty liver deposit, melena |

Endocrine

| Rare | hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, thyroiditis |

Hemic and Lymphatic System

| Infrequent | anemia, ecchymosis, leukocytosis, leukopenia, eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy |

| Rare | thrombocytopenia, hypochromic anemia, lymphocytosis, monocytosis, basophilia, lymphedema, polycythemia, thrombocythemia |

Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders

| Infrequent | thirst, transaminase increased, peripheral edema, hyperglycemia, creatine phosphokinase increased, alkaline phosphatase increased, hypercholesteremia, dehydration, lactic dehydrogenase increased, albuminuria, hypokalemia |

| Rare | BUN increased, creatinine increased, hyperlipemia, hypocholesteremia, hyperkalemia, hypochloremia, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypoproteinemia, glucose tolerance decreased, gout, hyperchloremia, hyperuricemia, hypocalcemia, hypoglycemic reaction, hypomagnesemia, ketosis, respiratory alkalosis |

Musculoskeletal System

| Frequent | myalgia |

| Infrequent | tenosynovitis |

| Rare | myopathy |

Nervous System

| Frequent | agitation, extrapyramidal syndrome, tremor, dystonia, hypertonia, dyskinesia, hostility, twitching, paresthesia, confusion, vertigo, hypokinesia, hyperkinesia, abnormal gait, oculogyric crisis, hypesthesia, ataxia, amnesia, cogwheel rigidity, delirium, hypotonia, akinesia, dysarthria, withdrawal syndrome, buccoglossal syndrome, choreoathetosis, diplopia, incoordination, neuropathy |

| Infrequent | paralysis |

| Rare | myoclonus, nystagmus, torticollis, circumoral paresthesia, opisthotonos, reflexes increased, trismus |

Respiratory System

| Frequent | dyspnea |

| Infrequent | pneumonia, epistaxis |

| Rare | hemoptysis, laryngismus |

Skin and Appendages

| Infrequent | maculopapular rash, urticaria, alopecia, eczema, exfoliative dermatitis, contact dermatitis, vesiculobullous rash |

Special Senses

| Frequent | fungal dermatitis |

| Infrequent | conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tinnitus, blepharitis, cataract, photophobia |

| Rare | eye hemorrhage, visual field defect, keratitis, keratoconjunctivitis |

Urogenital System

| Infrequent | impotence, abnormal ejaculation, amenorrhea, hematuria, menorrhagia, female lactation, polyuria, urinary retention metrorrhagia, male sexual dysfunction, anorgasmia, glycosuria |

| Rare | gynecomastia, vaginal hemorrhage, nocturia, oliguria, female sexual dysfunction, uterine hemorrhage |

BIPOLAR DISORDER

Acute Treatment of Manic or Mixed Episodes in Adults

Adverse Reactions Associated With Discontinuation of Treatment in Short Term, Placebo-Controlled Trials

Approximately 6.5% (18/279) of ziprasidone-treated patients in short-term, placebo-controlled studies discontinued treatment due to an adverse reaction, compared with about 3.7% (5/136) on placebo. The most common reactions associated with dropout in the ziprasidone-treated patients were akathisia, anxiety, depression, dizziness, dystonia, rash and vomiting, with 2 dropouts for each of these reactions among ziprasidone patients (1%) compared to one placebo patient each for dystonia and rash (1%) and no placebo patients for the remaining adverse reactions.

Adverse Reactions Occurring at an Incidence of 2% or More Among Ziprasidone-Treated Patients in Short-Term, Oral, Placebo-Controlled Trials

Table 12 enumerates the incidence, rounded to the nearest percent, of treatment-emergent adverse reactions that occurred during acute therapy (up to 3 weeks) in patients with bipolar mania, including only those reactions that occurred in 2% or more of patients treated with ziprasidone and for which the incidence in patients treated with ziprasidone was greater than the incidence in placebo-treated patients.

| Percentage of Patients Reporting Reaction | ||

|---|---|---|

| Body System/Adverse Reaction | Ziprasidone

(N=279) | Placebo

(N=136) |

|

||

| Body as a Whole | ||

| Headache | 18 | 17 |

| Asthenia | 6 | 2 |

| Accidental Injury | 4 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Hypertension | 3 | 2 |

| Digestive | ||

| Nausea | 10 | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 4 |

| Dry Mouth | 5 | 4 |

| Vomiting | 5 | 2 |

| Increased Salivation | 4 | 0 |

| Tongue Edema | 3 | 1 |

| Dysphagia | 2 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Myalgia | 2 | 0 |

| Nervous | ||

| Somnolence | 31 | 12 |

| Extrapyramidal Symptoms * | 31 | 12 |

| Dizziness † | 16 | 7 |

| Akathisia | 10 | 5 |

| Anxiety | 5 | 4 |

| Hypesthesia | 2 | 1 |

| Speech Disorder | 2 | 0 |

| Respiratory | ||

| Pharyngitis | 3 | 1 |

| Dyspnea | 2 | 1 |

| Skin and Appendages | ||

| Fungal Dermatitis | 2 | 1 |

| Special Senses | ||

| Abnormal Vision | 6 | 3 |

Explorations for interactions on the basis of gender did not reveal any clinically meaningful differences in the adverse reaction occurrence on the basis of this demographic factor.

6.2 Postmarketing Experience

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of ziprasidone. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Adverse reaction reports not listed above that have been received since market introduction include rare occurrences of the following : Cardiac Disorders: Tachycardia, torsade de pointes (in the presence of multiple confounding factors), [see Warnings and Precautions (5.3)] ; Digestive System Disorders: Swollen Tongue; Reproductive System and Breast Disorders: Galactorrhea, priapism; Nervous System Disorders: Facial Droop, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, serotonin syndrome (alone or in combination with serotonergic medicinal products), tardive dyskinesia; Psychiatric Disorders: Insomnia, mania/hypomania; Skin and subcutaneous Tissue Disorders: Allergic reaction (such as allergic dermatitis, angioedema, orofacial edema, urticaria), rash, Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS); Urogenital System Disorders: Enuresis, urinary incontinence; Vascular Disorders: Postural hypotension, syncope.

7 DRUG INTERACTIONS

Drug-drug interactions can be pharmacodynamic (combined pharmacologic effects) or pharmacokinetic (alteration of plasma levels). The risks of using ziprasidone in combination with other drugs have been evaluated as described below. All interactions studies have been conducted with oral ziprasidone. Based upon the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile of ziprasidone, possible interactions could be anticipated:

7.1 Metabolic Pathway

Approximately two-thirds of ziprasidone is metabolized via a combination of chemical reduction by glutathione and enzymatic reduction by aldehyde oxidase. There are no known clinically relevant inhibitors or inducers of aldehyde oxidase. Less than one-third of ziprasidone metabolic clearance is mediated by cytochrome P450 catalyzed oxidation.

7.2 In Vitro Studies

An in vitro enzyme inhibition study utilizing human liver microsomes showed that ziprasidone had little inhibitory effect on CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, and thus would not likely interfere with the metabolism of drugs primarily metabolized by these enzymes. There is little potential for drug interactions with ziprasidone due to displacement [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)] .

7.3 Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Ziprasidone should not be used with any drug that prolongs the QT interval [see Contraindications (4.1)] .

Given the primary CNS effects of ziprasidone, caution should be used when it is taken in combination with other centrally acting drugs.

Because of its potential for inducing hypotension, ziprasidone may enhance the effects of certain antihypertensive agents.

Ziprasidone may antagonize the effects of levodopa and dopamine agonists.

7.4 Pharmacokinetic Interactions

- Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine is an inducer of CYP3A4; administration of 200 mg twice daily for 21 days resulted in a decrease of approximately 35% in the AUC of ziprasidone. This effect may be greater when higher doses of carbamazepine are administered.

- Ketoconazole

Ketoconazole, a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, at a dose of 400 mg QD for 5 days, increased the AUC and Cmax of ziprasidone by about 35–40%. Other inhibitors of CYP3A4 would be expected to have similar effects.

7.5 Lithium

Ziprasidone at a dose of 40 mg twice daily administered concomitantly with lithium at a dose of 450 mg twice daily for 7 days did not affect the steady-state level or renal clearance of lithium. Ziprasidone dosed adjunctively to lithium in a maintenance trial of bipolar patients did not affect mean therapeutic lithium levels.

7.6 Oral Contraceptives

In vivo studies have revealed no effect of ziprasidone on the pharmacokinetics of estrogen or progesterone components. Ziprasidone at a dose of 20 mg twice daily did not affect the pharmacokinetics of concomitantly administered oral contraceptives, ethinyl estradiol (0.03 mg) and levonorgestrel (0.15 mg).

7.7 Dextromethorphan

Consistent with in vitro results, a study in normal healthy volunteers showed that ziprasidone did not alter the metabolism of dextromethorphan, a CYP2D6 model substrate, to its major metabolite, dextrorphan. There was no statistically significant change in the urinary dextromethorphan/dextrorphan ratio.

7.8 Valproate

A pharmacokinetic interaction of ziprasidone with valproate is unlikely due to the lack of common metabolic pathways for the two drugs. Ziprasidone dosed adjunctively to valproate in a maintenance trial of bipolar patients did not affect mean therapeutic valproate levels.

7.9 Other Concomitant Drug Therapy

Population pharmacokinetic analysis of schizophrenic patients enrolled in controlled clinical trials has not revealed evidence of any clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions with benztropine, propranolol, or lorazepam.

7.10 Food Interaction

The absolute bioavailability of a 20 mg dose under fed conditions is approximately 60%. The absorption of ziprasidone is increased up to two-fold in the presence of food [see Clinical Pharmacology (12.3)] .

8 USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

8.1 Pregnancy

Pregnancy Exposure Registry

There is a pregnancy exposure registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to atypical antipsychotics, including ziprasidone, during pregnancy. Healthcare providers are encouraged to register patients by contacting the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or online at http://womensmentalhealth.org/clinical-and-research-programs/pregnancyregistry/.

Risk Summary

Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs, including ziprasidone, during the third trimester are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery (see Clinical Considerations). Overall available data from published epidemiologic studies of pregnant women exposed to ziprasidone have not established a drug-associated risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes (see Data) . There are risks to the mother associated with untreated schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder and with exposure to antipsychotics, including ziprasidone, during pregnancy (see Clinical Considerations).

In animal studies, ziprasidone administration to pregnant rats and rabbits during organogenesis caused developmental toxicity at doses similar to recommended human doses, and was teratogenic in rabbits at 3 times the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD). Rats exposed to ziprasidone during gestation and lactation exhibited increased perinatal pup mortality and delayed neurobehavioral and functional development of offspring at doses less than or similar to human therapeutic doses ( see Data).

The estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage for the indicated populations is unknown. All pregnancies have a background risk of birth defect, loss, or other adverse outcomes. In the U.S. general population, the estimated background risk of major birth defects and miscarriage in clinically recognized pregnancies is 2 to 4% and 15 to 20%, respectively.

Clinical Considerations

Disease-associated maternal and/or embryo/fetal risk

There is risk to the mother from untreated schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, including increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and suicide. Schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder are associated with increased adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth. It is not known if this is a direct result of the illness or other comorbid factors.

Fetal/neonatal adverse reactions

Extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms, including agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress, and feeding disorder have been reported in neonates who were exposed to antipsychotic drugs, including ziprasidone, during the third trimester of pregnancy. These symptoms have varied in severity. Monitor neonates for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms and manage symptoms appropriately. Some neonates recovered within hours or days without specific treatment; others required prolonged hospitalization.

Data

Human Data

Published data from observational studies, birth registries, and case reports on the use of atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy do not report a clear association with antipsychotics and major birth defects. A retrospective cohort study from a Medicaid database of 9258 women exposed to antipsychotics during pregnancy did not indicate an overall increased risk for major birth defects.

Animal Data

When ziprasidone was administered to pregnant rabbits during the period of organogenesis, an increased incidence of fetal structural abnormalities (ventricular septal defects and other cardiovascular malformations, and kidney alterations) was observed at a dose of 30 mg/kg/day (3 times the MRHD of 200 mg/day based on mg/m 2 body surface area). There was no evidence to suggest that these developmental effects were secondary to maternal toxicity. The developmental no effect dose was 10 mg/kg/day (equivalent to the MRHD based on a mg/m 2 body surface area). In rats, embryofetal toxicity (decreased fetal weights, delayed skeletal ossification) was observed following administration of 10 to 160 mg/kg/day (0.5 to 8 times the MRHD based on mg/m 2 body surface area) during organogenesis or throughout gestation, but there was no evidence of teratogenicity. Doses of 40 and 160 mg/kg/day (2 and 8 times the MRHD based on mg/m 2 body surface area) were associated with maternal toxicity. The developmental no-effect dose is 5 mg/kg/day (0.2 times the MRHD based on mg/m 2 body surface area).

There was an increase in the number of pups born dead and a decrease in postnatal survival through the first 4 days of lactation among the offspring of female rats treated during gestation and lactation with doses of 10 mg/kg/day (0.5 times the MRHD based on mg/m 2 body surface area) or greater. Offspring developmental delays (decreased pup weights) and neurobehavioral functional impairment (eye opening air righting) were observed at doses of 5 mg/kg/day (0.2 times the MRHD based on mg/m 2 body surface area) or greater. A no-effect level was not established for these effects.

8.2 Lactation

Risk Summary

Limited data from a published case report indicate the presence of ziprasidone in human milk. Although there are no reports of adverse effects on a breastfed infant exposed to ziprasidone via breast milk, there are reports of excess sedation, irritability, poor feeding, and extrapyramidal symptoms (tremors and abnormal muscle movements) in infants exposed to other atypical antipsychotics through breast milk (see Clinical Considerations) . There is no information on the effects of ziprasidone on milk production. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother's clinical need for ziprasidone and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed child from ziprasidone or from the mother's underlying condition.

8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Infertility

Females

Based on the pharmacologic action of ziprasidone (D2 antagonism), treatment with ziprasidone may result in an increase in serum prolactin levels, which may lead to a reversible reduction in fertility in females of reproductive potential [see Warnings and Precautions (5.15) and Nonclinical Toxicology (13.1)].

8.4 Pediatric Use

The safety and effectiveness of ziprasidone have not been established in pediatric patients.

Ziprasidone was studied in one 4-week, placebo-controlled trial in patients 10 to 17 years of age with bipolar I disorder. However, the data were insufficient to fully assess the safety of ziprasidone in pediatric patients. Therefore, a safe and effective dose for use could not be established.

8.5 Geriatric Use

Of the total number of subjects in clinical studies of ziprasidone, 2.4 percent were 65 and over. No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between these subjects and younger subjects, and other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between the elderly and younger patients, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, the presence of multiple factors that might increase the pharmacodynamic response to ziprasidone, or cause poorer tolerance or orthostasis, should lead to consideration of a lower starting dose, slower titration, and careful monitoring during the initial dosing period for some elderly patients.

8.6 Renal Impairment

Because ziprasidone is highly metabolized, with less than 1% of the drug excreted unchanged, renal impairment alone is unlikely to have a major impact on the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone. The pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone following 8 days of 20 mg twice daily dosing were similar among subjects with varying degrees of renal impairment (n=27), and subjects with normal renal function, indicating that dosage adjustment based upon the degree of renal impairment is not required. Ziprasidone is not removed by hemodialysis.

8.7 Hepatic Impairment

As ziprasidone is cleared substantially by the liver, the presence of hepatic impairment would be expected to increase the AUC of ziprasidone; a multiple-dose study at 20 mg twice daily for 5 days in subjects (n=13) with clinically significant (Childs-Pugh Class A and B) cirrhosis revealed an increase in AUC 0–12 of 13% and 34% in Childs-Pugh Class A and B, respectively, compared to a matched control group (n=14). A half-life of 7.1 hours was observed in subjects with cirrhosis compared to 4.8 hours in the control group.

8.8 Age and Gender Effects

In a multiple-dose (8 days of treatment) study involving 32 subjects, there was no difference in the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone between men and women or between elderly (>65 years) and young (18 to 45 years) subjects. Additionally, population pharmacokinetic evaluation of patients in controlled trials has revealed no evidence of clinically significant age or gender-related differences in the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone. Dosage modifications for age or gender are, therefore, not recommended.

8.9 Smoking

Based on in vitro studies utilizing human liver enzymes, ziprasidone is not a substrate for CYP1A2; smoking should therefore not have an effect on the pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone. Consistent with these in vitro results, population pharmacokinetic evaluation has not revealed any significant pharmacokinetic differences between smokers and nonsmokers.

9 DRUG ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE

9.3 Dependence

Ziprasidone has not been systematically studied, in animals or humans, for its potential for abuse, tolerance, or physical dependence. While the clinical trials did not reveal any tendency for drug-seeking behavior, these observations were not systematic and it is not possible to predict on the basis of this limited experience the extent to which ziprasidone will be misused, diverted, and/or abused once marketed. Consequently, patients should be evaluated carefully for a history of drug abuse, and such patients should be observed closely for signs of ziprasidone misuse or abuse (e.g., development of tolerance, increases in dose, drug-seeking behavior).

10 OVERDOSAGE

10.1 Human Experience

In premarketing trials involving more than 5400 patients and/or normal subjects, accidental or intentional overdosage of oral ziprasidone was documented in 10 patients. All of these patients survived without sequelae. In the patient taking the largest confirmed amount, 3,240 mg, the only symptoms reported were minimal sedation, slurring of speech, and transitory hypertension (200/95).

Adverse reactions reported with ziprasidone overdose included extrapyramidal symptoms, somnolence, tremor, and anxiety. [see Adverse Reactions (6.2)]

10.2 Management of Overdosage

In case of acute overdosage, establish and maintain an airway and ensure adequate oxygenation and ventilation. Intravenous access should be established, and gastric lavage (after intubation, if patient is unconscious) and administration of activated charcoal together with a laxative should be considered. The possibility of obtundation, seizure, or dystonic reaction of the head and neck following overdose may create a risk of aspiration with induced emesis.

Cardiovascular monitoring should commence immediately and should include continuous electrocardiographic monitoring to detect possible arrhythmias. If antiarrhythmic therapy is administered, disopyramide, procainamide, and quinidine carry a theoretical hazard of additive QT-prolonging effects that might be additive to those of ziprasidone.

Hypotension and circulatory collapse should be treated with appropriate measures such as intravenous fluids. If sympathomimetic agents are used for vascular support, epinephrine and dopamine should not be used, since beta stimulation combined with α 1 antagonism associated with ziprasidone may worsen hypotension. Similarly, it is reasonable to expect that the alpha-adrenergic-blocking properties of bretylium might be additive to those of ziprasidone, resulting in problematic hypotension.

In cases of severe extrapyramidal symptoms, anticholinergic medication should be administered. There is no specific antidote to ziprasidone, and it is not dialyzable. The possibility of multiple drug involvement should be considered. Close medical supervision and monitoring should continue until the patient recovers.

11 DESCRIPTION

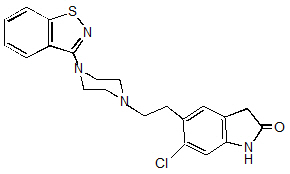

Ziprasidone contains the active moiety, ziprasidone in either the form of ziprasidone hydrochloride salt for capsules. Ziprasidone is a psychotropic agent that is chemically unrelated to phenothiazine or butyrophenone antipsychotic agents. It has a molecular weight of 412.94 (free base), with the following chemical name: 5-[2-[4-(1,2-benzisothiazol-3-yl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl]-6-chloro-1,3-dihydro-2 H-indol-2-one. The empirical formula of C 21H 21ClN 4OS (free base of ziprasidone) represents the following structural formula:

Ziprasidone capsules contain a monohydrochloride, monohydrate salt of ziprasidone. Chemically, ziprasidone hydrochloride monohydrate is 5-[2-[4-(1,2-benzisothiazol-3-yl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl]-6-chloro-1,3-dihydro-2 H-indol-2-one, monohydrochloride, monohydrate. The empirical formula is C 21H 21ClN 4OS ∙ HCl ∙ H 2O and its molecular weight is 467.42. Ziprasidone hydrochloride monohydrate is a white to slightly pink powder.

Ziprasidone capsules are supplied for oral administration in 20 mg (blue/white), 40 mg (blue/blue), 60 mg (white/white), and 80 mg (blue/white) capsules. Ziprasidone capsules contain ziprasidone hydrochloride monohydrate, lactose, magnesium stearate and pregelatinized starch. Each capsule for oral use contains ziprasidone hydrochloride monohydrate equivalent to either 20 mg, 40 mg, 60 mg, or 80 mg of ziprasidone.

12 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

12.1 Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of ziprasidone in the treatment of the listed indications could be mediated through a combination of dopamine type 2 (D 2) and serotonin type 2 (5HT 2) antagonism.

12.2 Pharmacodynamics

Ziprasidone binds with relatively high affinity to the dopamine D 2 and D 3, serotonin 5HT 2A, 5HT 2C, 5HT 1A, 5HT 1D, and α 1-adrenergic receptors (K i s of 4.8, 7.2, 0.4, 1.3, 3.4, 2, and 10 nM, respectively), and with moderate affinity to the histamine H 1 receptor (K i=47 nM). Ziprasidone is an antagonist at the D 2, 5HT 2A, and 5HT 1D receptors, and an agonist at the 5HT 1A receptor. Ziprasidone inhibited synaptic reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. No appreciable affinity was exhibited for other receptor/binding sites tested, including the cholinergic muscarinic receptor (IC 50 >1 µM).

12.3 Pharmacokinetics

Oral Pharmacokinetics

Ziprasidone's activity is primarily due to the parent drug. The multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of ziprasidone are dose-proportional within the proposed clinical dose range, and ziprasidone accumulation is predictable with multiple dosing. Elimination of ziprasidone is mainly via hepatic metabolism with a mean terminal half-life of about 7 hours within the proposed clinical dose range. Steady-state concentrations are achieved within one to three days of dosing. The mean apparent systemic clearance is 7.5 mL/min/kg. Ziprasidone is unlikely to interfere with the metabolism of drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes.

Absorption: Ziprasidone is well absorbed after oral administration, reaching peak plasma concentrations in 6 to 8 hours. The absolute bioavailability of a 20 mg dose under fed conditions is approximately 60%. The absorption of ziprasidone is increased up to two-fold in the presence of food.

Distribution: Ziprasidone has a mean apparent volume of distribution of 1.5 L/kg. It is greater than 99% bound to plasma proteins, binding primarily to albumin and α 1-acid glycoprotein. The in vitro plasma protein binding of ziprasidone was not altered by warfarin or propranolol, two highly protein-bound drugs, nor did ziprasidone alter the binding of these drugs in human plasma. Thus, the potential for drug interactions with ziprasidone due to displacement is minimal.